It was supposed to be the merger that would give birth to the “Internet century.” Stock analysts declared it would provide the “operating system for everyday life.” Instead, timed perfectly for the dotcom crash that would deflate AOL’s overheated stock, it would turn out to be one of the worst deals in corporate history. But before AOL Time Warner crashed and burned, there were people at Time Warner who hoped it might actually work.

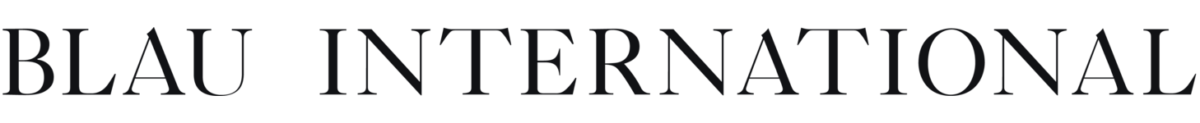

The convergence puzzle: From left, Time Warner CFO Richard Bressler; AOL CEO Steve Case; Time Warner president Richard Parsons; the late Steve Ross, who created Time Warner in a series of mergers; Jerry Levin, who succeeded him as Time Warner’s CEO; and AOL president Bob Pittman.

THESE DAYS, TIME WARNER execs do their best to avoid a word they used to flaunt: synergy. Besides sounding hopelessly dated, it’s a reminder of the miraculous burst of corporate creativity that was supposed to happen — and didn’t — when Time Inc. and Warner Communications merged in 1990. The last time a Time Warner exec said it to me, over breakfast at a Beverly Hills hotel, he lowered his eyes, produced an embarrassed half-smile, and dropped his voice so that nobody around us could hear, as if he were about to confess some strange sexual practice.

Which has to make you wonder about this whole AOL thing. The idea behind merging the world’s leading online services provider with the world’s biggest media and entertainment company is that together they can set the pace for what AOL chair Steve Case likes to call “the Internet century.” As Merrill Lynch analysts Henry Blodget and Jessica Reif Cohen put it in their fervent endorsement of the deal, AOL Time Warner will provide the “operating system for everyday life” in our fully interactive future — involving the way we communicate, get news and entertainment, go shopping, manage our money, do almost everything except eat and sleep. “We did the AOL merger because we thought we could get digital by injection instead of by evolution,” says Time Warner president Richard Parsons. Throw in the pending merger of Warner Music with EMI, the global music giant, and you have a media behemoth like no other.

But making it work depends on somebody getting all the parts to mesh. After all, this isn’t the first time Jerry Levin has tried to transform his company with a multibillion-dollar deal: As chief strategist at Time Inc., the high-WASP magazine empire whose profits were fueled by its déclassé cable-TV operations, he orchestrated the merger with Warner Communications because he decided Time Inc. had become too inbred to survive on its own. The acquisition of Turner Broadcasting in 1996 was supposed to complete the metamorphosis. What emerged instead was a corporate version of the Holy Roman Empire: a loose confederation of fiefdoms that are as likely to be at war with one another as with outsiders.

But making it work depends on somebody getting all the parts to mesh. After all, this isn’t the first time Jerry Levin has tried to transform his company with a multibillion-dollar deal: As chief strategist at Time Inc., the high-WASP magazine empire whose profits were fueled by its déclassé cable-TV operations, he orchestrated the merger with Warner Communications because he decided Time Inc. had become too inbred to survive on its own. The acquisition of Turner Broadcasting in 1996 was supposed to complete the metamorphosis. What emerged instead was a corporate version of the Holy Roman Empire: a loose confederation of fiefdoms that are as likely to be at war with one another as with outsiders.

“The internecine warfare is a meat-grinder,” says a Time Warner executive who’s watched the battling for years. Some of these clashes have become business legends — Time Warner Cable’s refusal to carry Turner’s struggling CNNfn network on many of its systems, for instance, and Warner Bros.’ reputed attempt to extract a billion-dollar licensing fee from Time Warner’s cable-modem partnership for use of the name Road Runner. Infighting can break out at any level — and with 70,000 employees and dozens of overlapping businesses, from Warner Bros. and HBO to Time Warner Cable and the WB network, that makes for a lot of possibilities. This pattern is reinforced by Levin, a CEO who expects double-digit year-after-year profit growth and does little to reward intramural niceness. At 75 Rock, the anonymous gray tower in New York’s Rockefeller Center that serves as Time Warner’s headquarters, businesses are judged by their contribution to the bottom line — period. “Time Warner is a series of sharp, tough, profit-oriented operating companies,” says one mid-level executive. “And, frankly, a lot of people really like it that way.”

Analysts fervently endorsed the marriage of old and new media: AOL Time Warner, they said, would become our “operating system for everyday life.”

For an analog-era media conglomerate, that’s fine. But in a digital environment, all media converge. Time Warner labored to get traction online, but turf battles and ego clashes hobbled every try, from the 1994 initiative that yielded its much-maligned Pathfinder Web site to last year’s attempt to form “vertical hubs” on the Web — a finance site, for example, built around Money, Fortune, and CNNfn. Many in the company believe that the collapse of that strategy amid the long knives of corporate infighting led inexorably to the decision to sell to AOL, the online upstart from Dulles, Virginia. “Any effort to do anything cross-divisionally has always been doomed,” says a Time Warner executive. “So how do you impose digits on an analog world? It can’t be done internally, so it has to be done externally — hence, the invasion of Dulles.”

LEADING THE CHARGE WILL BE AOL’S PRESIDENT, Bob Pittman, who’s poised to become one of two co-chief operating officers (with Time Warner president Richard Parsons) after the merger goes through. Pittman has an impressive track record as a mediator, innovator, and head knocker. When he came to America Online late in 1996, its stock was in free fall, its last president had quit four months into the job, and members were coming and going so fast that the word churn entered common business parlance. Pittman brought showbiz pizzazz, thanks to his high-profile history with MTV and Time Warner’s Six Flags amusement parks (since sold). He also brought discipline. By managing costs, developing new revenue streams, and delivering profits, he transformed AOL from a financial roller-coaster into a smooth and dependable performer. All this made him hot stuff on Wall Street.

A Decade of Reporting on the Global Media Conglomerates |

In the 1990s and into the 2000s, a series of ego-fueled mega-mergers led to the creation of six global media conglomerates: News Corp., Sony, AOL Time Warner, Vivendi Universal, Viacom and Walt Disney. For most, it would not end well. |

Can the PS3 Save Sony?The company that created the transistor radio and the Walkman is at the precipice.

|

Barry Diller Has No Vision for the Future of the InternetThat’s why the no-nonsense honcho of Home Shopping Network and Universal is poised to rule the interactive world.

|

The Civil War Inside SonySony Music wants to entertain you. Sony Electronics wants to equip you. Too bad their interests are diametrically opposed.

|

Big Media or BustAs consolidation sweeps the content and telecom industries, FCC Chairman Michael Powell has a plan: Let’s roll.

|

Vivendi’s High Wireless ActWill a global media company with continent-wide mobile distribution prove unbeatable?

|

Reminder to Steve Case: Confiscate the Long KnivesTime Warner brings fat pipe and petabytes of content to AOL—plus a long history of infighting and backstabbing.

|

TV or Not TVRupert Murdoch aims to capture Europe’s interactive TV market with a Sun set-top strategy. But a growing Microsoft alliance has different plans.

|

Think Globally, Script LocallyAmerican pop culture was going to conquer the world — but now local content is becoming king.

|

Edgar Bronfman Actually Has a Strategy—with a TwistThe Seagram heir is challenging Disney in theme parks and spending billions to be No. 1 in music. Can this work?

|

There’s No Business Like Show BusinessA handful of powerful CEOs are battling for the hearts, minds, and eyeballs of the world’s six billion people.

|

What Ever Happened to Michael Ovitz?Striving to make his comeback, CAA’s superagent is now an unemployment statistic. Seven lessons to be learned from the fall of the image king.

|

Can Disney Tame 42nd Street?Disney is pouring millions into one of Manhattan’s most crime-ridden blocks. What does Michael Eisner know that you don’t?

|

Twilight of the Last MogulLew Wasserman has been shaking Hollywood since the ’30s. When Seagram bought MCA, was he really out of the loop, or was he king of the dealmakers to the last?Los Angeles Times Magazine | May 21, 1995 |

But Pittman now faces a challenge like no other — riding herd on the largest corporate merger in US history, one that, spin notwithstanding, makes many AOL shareholders edgy. In June, when shareholders approved the deal — which still faces months of review before it passes muster with government regulators in the US and Europe — the only sour notes came from a few AOL kvetchers who asked the nagging question: Remind us again, why is this deal such a good move for our company? AOL’s stock slid 30 percent between January — when the merger was announced — and June, and though Steve Case attributes that entirely to tech-stock jitters, a lot of people are worried that AOL is about to swallow a porcupine.

“Time Warner culture can be so vicious that I think it could do serious damage to AOL,” says one Time Warner veteran. “AOL doesn’t have a clue what it’s taken on, despite Bob Pittman’s past involvement with Time Warner,” declares another. “This is a very complex, divided, and divisive animal.”

And what’s the mood at Time Warner? Depends on which principality you’re in. Although the company is officially organized into six divisions (publishing, cable systems, filmed entertainment, music, cable networks, and the recently formed digital media unit), people still think of it as Time, Warner, and Turner — or New York, Burbank, and Atlanta, as they’re commonly referred to. Atlanta remains a quasi-autonomous territory reporting to vice chair Ted Turner — which is why the announcement in May that he would cede control of the cable networks to Pittman met with disbelief there, even prompting talk that Turner (Time Warner’s largest shareholder) would turn against the deal. But much of the rest of Time Warner awaits AOL’s looming “digital override,” as Levin has so colorfully phrased it, with a stunned, vaguely hopeful acceptance.

The initial reaction was financial euphoria, since Time Warner stock options vested the moment its board voted to accept the deal. But it went further than that. Many divisions have been promoting their offerings on AOL for years, so they’re familiar with its ways and eager for its expertise.

“I look forward to learning what they can teach us,” says an executive on the film side in Burbank. “A lot of Time Warner assets could become ubiquitous in people’s lives, especially as we move to handheld and cellular devices. There could be magic.”

Across the country at the Time & Life Building, home of the magazine division, the feeling is equally enthusiastic. This isn’t a repeat of 1990, people will tell you, when the Ivy League acolytes of Henry Luce, Time‘s legendary patriarch, found themselves in bed with the fleshy vulgarians of Warner. Time Inc. has slipped into permanent casual-Friday mode since then, its sack suits replaced by jeans and khakis. AOL looks like a great fit, as in tune with Middle America as People or In Style. It’s easy to see how promotions on AOL’s opening screen could supercharge subscription drives: Within three weeks of its launch, Time Inc.’s latest offering, the amiably square eCompany Now, had racked up 30,000 subs thanks to promotions on AOL. It’s also easy to see how AOL’s dramatic reach might finally make the magazines a force on the Internet — something Time Inc. executives never accomplished.

“People have written that we’re going to lose all these managers, but that’s not such a bad idea,” says one insider. “They’re very capable of producing profits — they’re just not capable of moving into the 21st century.” A colleague is more blunt: “My fondest hope is that AOL will come in here and kick butt. What people are genuinely afraid of is that AOL will become just one more division.”

Theoretically, that could happen: Though AOL has been in hypergrowth, in revenue terms it merely looks like a neat addition to the Time Warner empire. The $5.7 billion it pulled in last year puts it about even with Time Warner’s cable systems division ($5.4 billion), but well behind cable networks ($6.1 billion) and filmed entertainment ($8.1 billion). Even after its slide, however, AOL’s market value stood at more than $120 billion — nearly 20 percent higher than Time Warner’s. But at a meeting of Time Warner finance people in Florida several weeks after the merger announcement, senior AOL executives declared that AOL was not going to be just another division — that they would be taking charge.

“AOL — they’re a different breed of cat,” says an executive familiar with both cultures. “First, there’s a 10-year-plus age differential between their work force and ours. Second, they’ve known only success, and therefore they’re fearless. And third, they are seeking to replace the existing order with a new order — so they’re different from people who are invested in the status quo.” AOL is always on, always hungry, always demanding something new. “The work ethic is intense, and there’s zero tolerance for not getting it done — but there’s so much team effort,” says one veteran. “This company is a force of nature and it has to dominate, because it’s unified, because it can only do one thing: put out the service, 24 hours a day. That’s what the old media world will never understand.”

TRUE ENOUGH. BUT THE NEW MEDIA WORLD HAD BETTER understand that when you marry a company like Time Warner, you run into some heavy legacy issues. AOL would be well advised to take a long look at Time Warner’s online track record, a tragicomic bumblefest that isn’t simply part of the past — it’s a guide to the dysfunctional present. It’s not as if Time Warner discovered the Internet yesterday: Prodded by a forward-looking CEO, it has long been in the vanguard of new media explorations. Trouble was, it inevitably ended up lost in the woods. “Jerry Levin really is a visionary,” says one veteran. “It’s just always been so much more difficult than he thought it would be.”

“My fondest hope is that AOL will come in here and kick butt. But people are genuinely afraid AOL will become just one more division of Time Warner.”

Nowhere was it more difficult than in Orlando, Florida, where Time Warner spent at least $100 million developing the interactive television of the future, only to discover that it didn’t work. At the same time, it blew the chance to buy the future wholesale: In 1994, the year Levin unveiled the Full Service Network in Orlando, Microsoft cofounder Paul Allen put his 25 percent stake in AOL — then worth $200 million or so — on the market. (Such a stake would now be worth around $14 billion.) Meanwhile, a committee of Time Warner execs looked at the idea of buying AOL or a competing online service, but opted instead to go with Pathfinder, the Web site Time Inc. had been developing.

They ended up with a poster child for old media cluelessness, ridiculed for its regurgitated magazine content and revolving-door management, for burying some of the best media brands on the planet under a moniker no one knew. But Pathfinder didn’t start out as a joke. In 1994, long before the word portal was applied to the Internet, it was envisioned by its cofounders, Time Inc. New Media execs Walter Isaacson and Jim Kinsella, as a “gateway” to the World Wide Web, with free email and a search engine and material from across Time Warner.

The reasoning was prescient: Online access would soon become a low-margin commodity, like PCs or refrigerators. What had value was all the stuff you could do once you got there — chat, email, surf, play games. The ambition, in other words, was to be AOL.

But top-level zeal for the project was almost nil — witness Time Inc. chair Don Logan’s notorious 1995 remark that Pathfinder had “given new meaning to the term black hole.” The search engine and other features were stalled for lack of funding, and internal rivalries were so bad that Isaacson and Kinsella couldn’t even get Sunset, Southern Living, and Time Life Books to collaborate on a simple gardening site.

It was also a matter of priorities: At Time Inc., old media came first. After Isaacson was anointed managing editor of Time in late 1995, Logan’s charge to Isaacson’s successors wasn’t to build Pathfinder into a leading destination on the Web; it was to learn as much as possible, lose as little as possible, and figure out how new media could help Time’s existing businesses. But most magazine editors didn’t see how a medium that’s on 24/7 could do anything but steal away readers. It wasn’t until after Princess Diana’s 1997 car crash, when People broke news about the investigation online and got a huge spike in Web traffic with no drop in newsstand sales, that People’s editor got it: The Web version could actually fuel demand for the print product.

“Great,” says one ex-Pathfinder executive. “The only problem was, it happened two-and-a-half years too late — and there were still 10 or 20 other editorial types who needed to have their own V8 moment.”

Pathfinder was hardly the only Web scheme to go awry at Time Warner. It happened again in 1997 — before Yahoo! became an unassailable brand — with a planned Web portal known as Go2, a project that won approval from corporate higher-ups only to expire in a welter of meetings. And then again with Entertaindom, the site that became the centerpiece of last year’s ill-fated hub strategy. Each time, a handful of eager scouts got a green light from the top, only to be ambushed by everyone else along the way.

Both Go2 and Entertaindom came out of Warner Bros., which was trying to figure out what the Internet could do for entertainment. The studio first went online through AOL, licensing a version of the soft-news TV show Extra in 1994. Warner Bros. Online was set up two years later, when Jim Moloshok, the television executive who’d made the Extra deal, enlisted Jim Banister from the CD-ROM group and Jeff Weiner from strategic planning.

By early 1997, Banister was looking beyond entertainment. He’d hooked up with Rich Zahradnik, vice president of CNNfn.com — the Internet half of CNN’s business-news channel, and the only Web site at Time Warner that was actually making money. Zahradnik and Banister were collaborating on a plan for a search engine that would serve as a Web portal. With almost touching boosterism, they dubbed it Go2: Go Time Warner Online.

Time Warner’s online track record is a tragicomic bumblefest, but it’s not simply part of the past — it’s a guide to the dysfunctional present.

A year and a half had passed since Kinsella’s gateway proposal; Banister and Zahradnik were thinking of something more like Yahoo! than AOL. They created a prototype and started to sell the idea to Time Warner CFO Richard Bressler. That fall, at a summit meeting Bressler hosted in the Time Inc. cafeteria, thirty-odd executives from around the company watched a carefully scripted demonstration and batted the idea around. After that came more meetings — with the cable networks, with the studio, with Time Inc. All the while, Yahoo!’s stock was trending upward.

Then, in early 1998, Yahoo! nearly doubled; by mid-July it nearly doubled again. Suddenly Time Warner was in a different game. The surge in Yahoo!’s market cap signaled not just Wall Street’s validation of the Web but its judgment that brand-name content like Time Warner’s was largely irrelevant. Eyeballs — valued for their direct connection to the brain, the purchasing center of the body — were the prize everyone was after, and the way to get them was to offer some sort of guide to the vast cornucopia of stuff online. But Time Warner had dithered too long to build a portal, so — like Sony, Disney, and almost every other media giant — it had to think about buying one.

Moloshok was drafted into the discussions, along with Linda McCutcheon, his counterpart at Time Inc. New Media. They talked with CNET about buying Snap!, with Compaq about buying AltaVista, with LookSmart, with Excite — but nothing got beyond Richard Bressler and his corporate finance team. “He was trying to come up to speed on new media,” McCutcheon recalls. “But the first time you look at a dotcom balance sheet, it’s a sobering and scary moment.”

Banister told Moloshok he was wasting his time with Bressler. While those two were off kicking tires in Silicon Valley, Banister had concluded that entertainment would be the next big thing on the Web. Microsoft and AOL had both invested heavily in original online entertainment in 1996, then bailed because they weren’t getting enough traffic. But it was time to look again, Banister argued: Modem speeds were increasing, streaming audio and video technologies were progressing rapidly, and the online population was about to reach critical mass. So in June 1998 — the same month NBC bought into Snap! and Disney bought a chunk of Infoseek — he and Weiner wrote a business plan for Entertaindom: a mass-appeal site that would feature shows from a variety of producers, just like a TV network.

With money from the studio, Banister started work on a prototype. Levin saw a demo in March 1999. The next thing they knew, he mentioned it in a talk. Then Bressler phoned to say that Entertaindom would be funded — and that it would be taken out of Warner Bros. and put into a new unit they were setting up at the corporate level, Time Warner Digital Media. It would be Time Warner’s entertainment hub on the Web, with original programming, sure, but also profiles and reviews from other Time Warner properties like Entertainment Weekly and In Style. There’d be other hubs as well — finance, news, sports. And the head of Time Warner Digital Media? Bressler himself. Suddenly this Web stuff was important. The message was clear: You guys were the B team, now here comes the A team — so get out of the way!

WHAT HAD CHANGED WAS THIS: Wall Street wanted to see an Internet strategy, pronto. Disney had one: Together with Infoseek, it had just launched the Go Network, with the expectation that it would soon be among the top three Web properties in the US. (It wouldn’t, but who knew?) Time Warner needed one, too.

And who better than Richard Bressler to run it? In March 1995, when Bressler was named CFO, Time Warner was $15 billion in debt and its stock was flatlining, even though operating income was up across most of the company. Not quite four years later, the stock was trading at record highs and the debt, while still staggering, had been refinanced on far less onerous terms. Clearly, Bressler was a genius. The feeling on the board was that he had a lot of potential as an operating officer, though first they had to try him out. He’d spent a year evaluating portal deals; digital was perfect.

The joke in New York was that the new head of Time Warner Digital Media would be deciding their digital future on the same day his secretary taught him to use email.

Bressler declined comment for this article. But insiders say he was the last person they’d expect to find in charge of digital media: “I could name 50 other people at Time Warner — well, maybe 25 — who knew more about the subject,” says one. The joke in New York was that Bressler would be deciding their digital future on the same day his secretary taught him to use email. “His knowledge of new media seemed to be gleaned largely from reading Fortune,” says another insider. “It was painful to try to explain all these things — firewalls, server farms, bandwidth constraints. It was New Media 101.”

As for the vaunted hub strategy, many within the company viewed it as little more than a press release. Announced in June after months of internal meetings, it coincided with the promulgation of Levin’s “Visions and Values” initiative, a warm ’n’ fuzzy drive that was supposed to make Time Warner a more integrated company.

On a superficial level it made sense. But if Pathfinder cofounder Walter Isaacson, whose political skills are regarded around Time Inc. with genuine awe, couldn’t find the magic formula, what hope did Bressler have of melding all of Time Warner in his first try at running something? And Digital Media was just a committee anyway: Bressler and the heads of Time Inc., Turner, and Warner Bros., with some corporate bean counters for staff and a former Time Inc. executive named Michael Pepe as Bressler’s second-in-command.

“They were in a dark room, feeling their way along the wall,” says a former Time Inc. executive, “trying to come up with something that sounded credible next to Disney’s carefully articulated Go Network plan. But it was Monty Python’s Flying Circus. ‘Do we want our hub to be a traffic aggregator?’ ‘What is a traffic aggregator?’ ‘What’s a hub again?’ In a room of 30 people, there’d be 27 trying desperately to pretend they understood what was going on and 3 banging their heads on the table, crying, ‘Oh God, please make this stop!’”

The people who were actually supposed to build the hubs were scattered throughout the company — and getting them to work together was a job for the UN. There were dustups over news, but the real donnybrook came over the financial hub, which was supposed to combine the sites of CNNfn, Money, and Fortune in a powerful financial-services destination that some thought could rival Quicken.com. The obvious thing to call it was Money.com — but Money.com belonged to Time Inc., whose execs didn’t want Turner running a Web site with their name on it. And CNNfn thought handing the site to Time Inc. would be tantamount to rewarding its failure with Pathfinder.

“They were trying to use it as a land grab,” gripes a Turner insider. “Their approach was, ‘We failed, so let us run it.’” Then, in June, CNNfn imploded: President Lou Dobbs quit after a blowup with the Turner brass over Space.com, his startup site on space exploration, just as the two executives running CNNfn’s Web site left to start MyPrimeTime.com, a self-actualization portal for baby boomers. Time Inc. won by default.

Meanwhile, Entertaindom’s launch date slipped from March to May to November 1999 as Moloshok and Weiner found themselves flying to New York for meetings, drawing up one business plan after another, and trying to line up content in their spare time. But making content deals wasn’t easy: Entertaindom didn’t have the budget for Hollywood paychecks and, unlike a startup, it wasn’t free to hand out stock options either — even though Time Warner had reluctantly agreed to spin it off as a separately traded company, with staffers getting options on 20 percent of its shares.

“Levin was so frustrated,” says a Time Warner vet: “‘Do I want to let infighting kill the company? Fuck everybody else — I’m going to do what’s best for the shareholders.’”

Moloshok had been hoping to give equity to five or ten big stars who’d do some programming and go on The Tonight Show to talk about it — the kind of arrangement Shockwave subsequently made with Tim Burton. But this rang all the wrong bells at corporate. What if the cast of Friends (broadcast on NBC but produced by Warner Bros.) asked for chunks of Time Warner the next time their contracts came up for renewal? Where would it end?

By the time Entertaindom finally launched at the end of November, half of Hollywood was planning entertainment Web sites and Time Warner’s digital hub strategy was a shambles. Executives who’d been recruited to work with Bressler were seething, not just over his lack of Net savvy but over his reluctance to risk confrontations or make tough decisions. But Parsons doesn’t blame Bressler: “As we got further into trying to implement the hub strategy,” he says, “it became clear that this was going to be more expensive, more time-consuming, and riskier than something like a merger” — the merger Levin and Bressler were already hammering out with AOL.

“A company like Time Warner is not built for innovation,” one veteran says wearily. “These are people who are running multi-billion-dollar businesses, and they don’t have the luxury of breaking eggs. How do you protect what you’ve got? That’s the focus of a mainstream media company. Jerry Levin is one of the smartest men I’ve seen — he sees things other people don’t see. And there were great opportunities — but that’s like saying that if I could fly, I would be Superman.”

“Levin was so frustrated,” says another Time Warner veteran. “He’s the smartest, the most dedicated — his heart is in the company. Not everybody in that building is the same way. So maybe Levin said, ‘Do I want to let infighting kill the company, or do I eliminate the infighting and solve the problem with Wall Street over a new media strategy at the same time? Fuck everybody else — I’m going to do what’s best for the shareholders.’ Now the problem children are being turned over to AOL to manage, and the only thing Levin has to worry about is, was it the right move for the shareholders?”

FOR JIM MOLOSHOK, THE AOL DEAL SEEMED like a vindication. Entertaindom might be late, but it was still pretty hot stuff, and Moloshok, who’d been cutting deals with AOL for years, was figured to be the point man for the integration of Warner Bros. into the new company. As it happened, Moloshok was the one on the way out. Weeks after Levin’s visit, Entertaindom — the only hub that actually got off the ground — was abruptly shifted out of Digital Media and back to Warner Bros. Then the company backed off its plan to take the site public and offered options on Time Warner stock that were both more restrictive and less lucrative. After all, how could Time Warner justify a deal that might make people in a division of a division richer than all but a handful of top corporate execs? Besides, it wasn’t exactly desperate to go digital any longer: It had AOL.

By late this March, Moloshok, Banister, and Weiner were negotiating their exits. By early April, Entertaindom staffers were bailing right and left. On the day the three founders’ departure was announced, flyers appeared on the Warner Bros. lot offering bounties for successful referrals to the Warner Bros. New Media division — $1,500 for a secretary, $2,500 for a supervisor, $5,000 for “manager and above.” Across the country at CNNfn — where the staff was still demoralized from Dobbs’ defection the year before — the mood was almost as dour. “These are people who thought they were building good sites,” says Rich Zahradnik, who’s now president of Goalnetwork.com. “There’s a good amount of fear and loathing.”

“AOL knows exactly what they’re going to get. They don’t care. They’re going to blow right over it. It’s no different from getting Netscape.”

Meanwhile, very little noise was coming out of 75 Rock. An ominous sign? Hard for Time Warner’s problem children to say. The corporate map was being redrawn by a four-man consolidation committee: Bressler and Time Warner president Richard Parsons from New York, and, from Dulles, AOL president Bob Pittman and vice chair Ken Novack, a close confidante of Steve Case. It was part of the deal that Case would be chair and Levin CEO, with Pittman and Parsons reporting to Levin as co-COOs — but how they’d divvy up the job was anyone’s guess. There was constant traffic between Dulles and New York, Dulles and Burbank, Dulles and Atlanta, yet nobody below the top levels of Time Warner’s six divisions was being consulted. So people kept a close eye on the gossip columns and waited.

Then, in early May, word came down. Pittman would take AOL, plus magazine publishing, cable systems, cable networks, and The WB — in other words, everything that brings in money from advertising and/or subscriptions. Parsons would get music, filmed entertainment, and book publishing — that is, everything that’s pure content (and vulnerable to free distribution on the Internet). It wasn’t hard to imagine Time Warner as a train coming uncoupled in the Old West, its front half pulling away under Pittman as the back half grinds slowly to a halt beneath the blistering desert sun. “Pittman captured the future,” one insider declares. “Parsons probably won’t stick around.”

Pittman wasn’t available for comment, but Parsons sounds committed: “My focus, and certainly Bob’s, is let’s make this thing work,” he says.

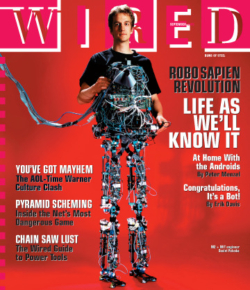

AOL Time Warner takes shape: CEO Jerry Levin with his designated co-COOs, Time Warner president Richard Parsons, standing at left, and AOL president Bob Pittman. Photo: Chester Higgins Jr./The New York Times

There were other developments as well. Ted Turner was relegated to an advisory role — and despite the talk that he’d try to scuttle the deal in retaliation, he’d already signed an agreement with AOL to approve it. Bressler was made head of a venture capital fund, scouting strategic investments. David Colburn, AOL’s ace dealmaker, was put in charge of business development, reporting to Pittman. Colburn is one of the brains who got AOL where it is today — the architect of such stunners as the March 1996 deal to license Netscape’s Web browser, followed the next day by an agreement with Microsoft to make Internet Explorer its primary browser. How many venture investments can be made without Colburn’s participation? Depending on the answer to this question, Bressler’s new position may be largely ceremonial.

But the big if involves Pittman: How are his partnerships with Jerry Levin and Dick Parsons supposed to work? At AOL, he and Case simply took separate roles. “Steve’s the big thinker,” says an industry exec. “Bob’s more of an operator. And Bob’s deal with Steve is that Steve doesn’t touch the business.” But that’s the deal Levin has now made with Case. Pittman’s deal with Levin, presumably, is to keep his part of the company in shape and stay out of trouble.

That could be hard. Pittman’s strengths have always been clear — a fantastic talent for promotion, an ability to interpret research and spot trends before they happen. “Bob really makes a point of understanding the consumer,” says Lee Masters, CEO of Liberty Digital, who’s known him since they were both teenage DJs in the ’60s. “Because if you’re not promoting the right thing, it doesn’t do you any good.” Yet Pittman’s flair for self-promotion can rankle: At MTV he got a bad rep for trying to pass himself off as the channel’s creator (the idea wasn’t his, though the execution was). Later, as an adviser to then-cochair Steve Ross at Time Warner before he took over Six Flags, he turned up in gossip columns as a candidate for other executives’ jobs.

At AOL Time Warner, the only job he’d want is Levin’s. True, the obvious setup for competition is between Pittman and Parsons. “With Pittman taking over all the pipes,” says Jim Moloshok, “he can say to the other half of the company, ‘This is what we need to satisfy the pipe.’ I can see Pittman redirecting the studio to create short-form content for the Internet instead of half-hour comedies.”

But Parsons is viewed as a self-effacing guy — someone who’ll keep his head down and do his job and not fight Pittman to get in the limelight. The real danger of conflict is with Levin, whose contract was just renewed through 2003 (with three-quarters of the board required to unseat him), and with the division heads who will now be reporting to Pittman.

These people have worked closely with Levin for years, and it’s hard to imagine him suddenly handing them off to Pittman. It’s not just that — in a company where these distinctions still matter — Levin was a Time Inc. man while Pittman was a protégé of Steve Ross, the legendary entrepreneur who cobbled together Warner Communications. It’s that Time Warner is Levin’s entire life. “Jerry Levin is never off,” says a well-placed industry executive. “He’s there from 7:30 am till 11 at night — and you can get an email back from him in five minutes. He sits down with these guys individually: ‘What are your issues? What are your needs? How is your quarter?’ They’re going to look at Pittman, as they often did at Parsons, and say, ‘What value does he bring to my day?’”

In the redrawn corporate map, Parsons gets pure content. Pittman gets everything that brings in money from ads or subscriptions — “the future.”

That assumes they have the luxury of asking such a question. Because the new structure doesn’t just give Pittman control of the pipe. It also makes Mike Kelly, AOL’s chief financial officer, CFO of the combined company. It puts Ken Lerer, a longtime Pittman associate who left his high-powered New York PR firm to join AOL, in charge of strategic positioning, corporate communications, and investor relations: an entire spin hospital. AOL’s general counsel, AOL’s CTO, AOL’s vice president for public policy — every one of them will take that job in the new company. Sure, the Time Warner bosses will keep on heading their divisions, but they’ll answer to a whole new crew.

“AOL knows exactly what they’re going to get,” says a veteran Time Warner executive. “But they don’t care. They’re going to blow right over it. It’s no different from getting Netscape, and all those people who say the Internet ought to be free. They’ll say ‘Left!’ and you’ll go left. They’ll say ‘Right!’ and you’ll go right. It’ll be handled, or the people who don’t like it will leave.”

The future headquarters of AOL Time Warner on Manhattan’s Columbus Circle.

THE FUTURE HEADQUARTERS OF AOL TIME WARNER is a teardown now — a cavernous, half-chewed box at the southwest corner of New York’s Central Park, its top pulled off, its walls disappearing foot by foot. Traffic spins past it around a newly spiffed-up Columbus Circle, a statue of the great explorer gazing downtown toward a New World as fountains play at his feet. Three years in the future, 75 Rock and the Time & Life Building and CNN’s New York offices and studios will be emptied and the company will regroup here, in one of two crystalline glass shafts set to rise high over Central Park. From the new headquarters you’ll see luxury condos and an ultra-posh Mandarin Oriental hotel in the other tower, with a jazz performance space for Lincoln Center in between. Quite a contrast to 22000 AOL Way in Dulles, a brittle glass-and-stone edifice deposited in the middle of nowhere, with nothing for company but the Wal-Mart across the road.

Like 75 Rock, 22000 AOL Way is a sealed-off place where decisions get made that the denizens of AOL’s other three buildings — the “creative centers” known, rather uncreatively, as CC1, CC2, and CC3 — find out about in the papers. People at CC1-3 assume that as soon as the merger goes through this fall, Bob Pittman will put Dulles in his rear-view mirror. Of course, to the AOL troops, that means he wants to be in New York with them — the Time Warner people, who are being paid shitloads of money in order to collect scores of perks — instead of us. But it’s also rumored that once the new headquarters opens, some of AOL’s creative types will move up to New York with him.

Are they ready? You bet! There are no movie screenings in Dulles, no nightclubs, no concert halls, no nonfranchised restaurants, no gourmet food stores or jewelry shops or expensive designer boutiques — just an army of AOL employees who work very, very hard all day, then go home to their bedroom-community condos and collapse until it’s time to come back and do it again.

Creative Center 2 is one of several newly constructed additions to AOL’s campus, a 154-acre office park in the far outskirts of Washington, DC.

September 1, 2000

September 1, 2000