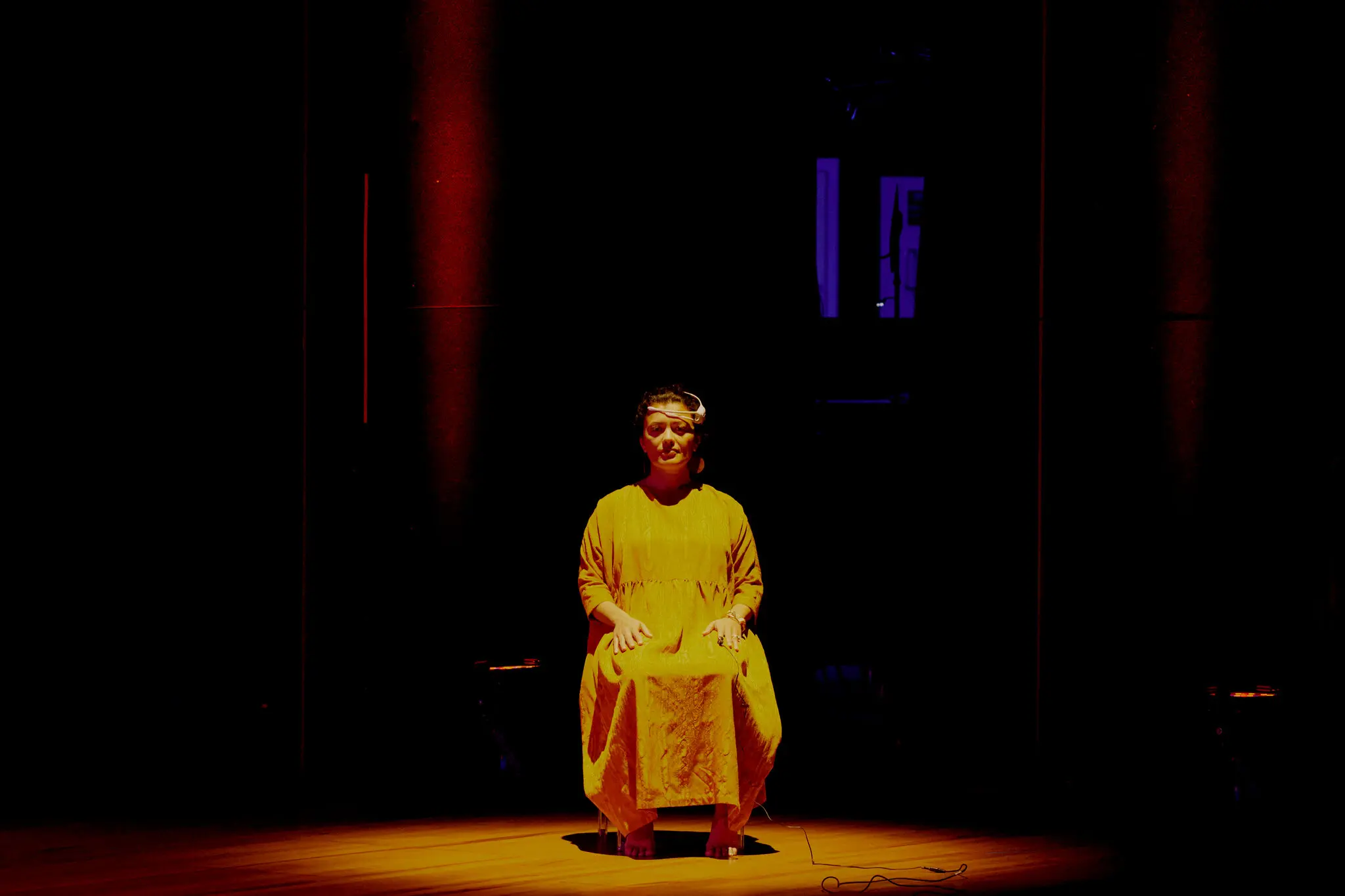

FCC Chair Michael Powell

TO THE CASUAL OBSERVER, AOL TIME WARNER might seem big enough. The world’s largest media company, it pulled in $38 billion last year from a staggering range of products — The Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter, ER and Friends, HBO and CNN and TNT, Madonna and Linkin Park, Sidney Sheldon and James Patterson, Time and People, AOL and Netscape, Time Warner Cable. But corporations have to keep growing — that’s the first rule of Wall Street. And even though AOL was outbid last year for AT&T Broadband, there are plenty of consolation prizes. Cablevision would be a good fit, and AOL might even be able persuade Cox to sell out too. But why stop with cable? As long as it’s buying stuff, AOL might as well think big. NBC has long looked tempting . . . but a takeover of Walt Disney would net ABC and ESPN, with Mickey Mouse thrown into the bargain. A really forward-looking CEO might then want to hedge his bets by buying a phone company, since sooner or later the phone lines will also deliver video. AOL Time Warner Cox Cablevision Disney Verizon? Why the hell not?

Until a year or so ago, such a scenario would have seemed ludicrous. Buying up Cox and Cablevision would take the company past the limit of pay-TV subscribers set by the FCC. And a deal with NBC or Disney would run up against another FCC rule that prohibits companies from owning a cable system and a TV station in the same market. A merger with Verizon would just seem off the wall. But in Washington today, the sky is pretty much the limit.

The man who’s set it there is Michael Powell, the 38-year-old antitrust attorney who heads the FCC. When President Bush appointed him in January 2001, Powell effectively became chief steward of the global information economy, charged with overseeing the entire spectrum of electronic media and communications. He comes to the job at a pivotal moment. After two decades of consolidation, scores of media companies have been reduced to six global conglomerates — AOL Time Warner, News Corp., Sony, Viacom, Vivendi Universal, and Disney. Four telcos — BellSouth, Qwest, SBC, and Verizon — own the lines into nearly every home and business in the US. AOL Time Warner commands nearly a third of total hours spent online — more than Microsoft, Yahoo!, and the next 17 companies combined. Now, with digital convergence fast blurring the boundaries among cable, telecom, and the Internet, the pace of consolidation is picking up. “I think we are very far from the end of this movement,” says Jean-Marie Messier, CEO of Vivendi Universal.

Where will it take us? Powell’s not sure — but he’s also not worried. “Monopoly is not illegal by itself in the United States,” he points out. “People tend to forget this. There is something healthy about letting innovators try to capture markets. What’s not healthy is if they can control them in a way that leads to anticompetitive effects for consumers.”

Where will it take us? Powell’s not sure — but he’s also not worried. “Monopoly is not illegal by itself in the United States,” he points out. “People tend to forget this. There is something healthy about letting innovators try to capture markets. What’s not healthy is if they can control them in a way that leads to anticompetitive effects for consumers.”

Less sanguine observers fear that further consolidation will lead to no good. They see a glimpse of the future in last year’s fight for AT&T Broadband, which took a strange twist when Microsoft offered to back either Comcast or Cox with cash in order to keep AT&T Broadband from going to its arch rival, AOL. “Sometimes, in an honest moment, you’ll hear someone at the FCC say that Microsoft and AOL Time Warner can police each other,” says Reed Hundt, who headed the FCC in the mid-’90s. “But no one self-polices antitrust. What Powell is doing is abdicating the responsibility Congress has given him. It’s extraordinarily lawless, and it disserves the country’s interests. He proposes to allow the creation of the greatest, most prodigiously sized media conglomerates that have ever bestrode the planet. And he seems massively indifferent to whether markets are competitive.”

“Reed will be Reed,” Powell responds. “I would say this is sort of melodramatic and preposterous. It’s also very interesting that the big companies we’re talking about are ones that became big prior to my tenure. To be ranting about abdication — I just think that’s sort of amazing, coming from a person who had these responsibilities himself.”

Of course, no FCC chief acts alone: The commission answers to Congress and to the federal courts, which last year overturned a long-standing rule limiting the percentage of the market a cable operator can control. But Powell could have appealed the order, or tried to devise a rationale for the cable cap that the court would accept. Instead, he launched a study to see if any cap is justified at all. He’s been questioning other FCC rules as well — regulations that keep a newspaper from owning a TV station in the same city, that limit the number of stations a broadcaster can own, that put a ceiling on the amount of spectrum a wireless carrier can buy.

These are the sort of arcane regulatory issues that generate small headlines in the business pages but have huge effects in the real world. And when they involve media companies, which are held to a far stricter standard than ordinary enterprises, the stakes go way up. “It’s a very fuzzy area,” Powell says, “because it’s very hard to find measurable things to have the debate around. Diversity and all that stuff is very important, but it’s hard to get a consensus on what it is, other than that the goals are worthy. I mean, if Viacom wants to buy so-and-so, is that the straw that broke the camel’s back?”

Which is precisely the question. The story of Viacom is the story of the media business: From its start as a small-time distributor peddling I Love Lucy reruns in the 1970s, it’s become the world’s third-largest media conglomerate, with sales last year of $23 billion and properties that include Paramount Pictures, CBS, MTV, Showtime, the Infinity radio-station chain, and Simon & Schuster books.

The paradox is that even as Viacom and the others have binged on mergers and ballooned to gargantuan proportions, the choices available to consumers have proliferated. “By any measure the media is wider, more diverse, and more varied than it’s ever been in history,” Powell claims — and he’s right. The reason is technology. Viewers in the ’50s had three channels at most; now they have hundreds of channels to choose from on cable or satellite, not to mention alternatives like videocassettes, DVDs, and the Web. Only the number of owners has shrunk.

“Powell is abdicating the responsibility Congress has given him,” says predecessor Reed Hundt. “It’s extraordinarily lawless, and it disserves the country’s interests.”

The telecom business, on the other hand, has until recently been on the opposite trajectory. After decades as a government-sanctioned monopoly, it was forcibly dismembered in 1984 with the court-ordered breakup of AT&T. The Telecommunications Act of 1996, the first major overhaul of communications law in 62 years, yielded an explosion of startups offering high-speed Internet access and other services. Then WorldCom swallowed up MCI and the Internet backbone provider UUNet, and the seven regional Bell companies merged into four, each enjoying a de facto monopoly on local service in its territory. Meanwhile, most of the startups collapsed into bankruptcy as funding dried up. Now we’re at the threshold of once-unimaginable combinations. In the near term, the surviving Bells seem destined to win control of the faltering long distance giants, AT&T, Sprint, and WorldCom — and with them, the bulk of the Internet backbone. On a farther horizon, some see the day when the phone companies will merge with the media conglomerates to form a digital hybrid of entertainment and telecom.

A Decade of Reporting on the Global Media Conglomerates |

In the 1990s and into the 2000s, a series of ego-fueled mega-mergers led to the creation of six global media conglomerates: News Corp., Sony, AOL Time Warner, Vivendi Universal, Viacom and Walt Disney. For most, it would not end well. |

Can the PS3 Save Sony?The company that created the transistor radio and the Walkman is at the precipice.

|

Barry Diller Has No Vision for the Future of the InternetThat’s why the no-nonsense honcho of Home Shopping Network and Universal is poised to rule the interactive world.

|

The Civil War Inside SonySony Music wants to entertain you. Sony Electronics wants to equip you. Too bad their interests are diametrically opposed.

|

Big Media or BustAs consolidation sweeps the content and telecom industries, FCC Chairman Michael Powell has a plan: Let’s roll.

|

Vivendi’s High Wireless ActWill a global media company with continent-wide mobile distribution prove unbeatable?

|

Reminder to Steve Case: Confiscate the Long KnivesTime Warner brings fat pipe and petabytes of content to AOL—plus a long history of infighting and backstabbing.

|

Think Globally, Script LocallyAmerican pop culture was going to conquer the world — but now local content is becoming king.

|

Edgar Bronfman Actually Has a Strategy—with a TwistThe Seagram heir is challenging Disney in theme parks and spending billions to be No. 1 in music. Can this work?

|

There’s No Business Like Show BusinessA handful of powerful CEOs are battling for the hearts, minds, and eyeballs of the world’s six billion people.

|

What Ever Happened to Michael Ovitz?Striving to make his comeback, CAA’s superagent is now an unemployment statistic. Seven lessons to be learned from the fall of the image king.

|

Can Disney Tame 42nd Street?Disney is pouring millions into one of Manhattan’s most crime-ridden blocks. What does Michael Eisner know that you don’t?

|

Powell views all this through an intellectual prism. He often cites the ideas of Joseph Schumpeter, the Harvard economist who’s now, more than 50 years after his death, considered a harbinger of the new economy. Schumpeter is best known for his theory of creative destruction — the idea that innovation and entrepreneurship give rise to a “perennial gale” that wreaks havoc in business, bringing in the new, destroying the old. (See “The Father of Creative Destruction.”) For a Republican trying to balance free-market principles with the task of government oversight, this concept offers some useful tips. Since Schumpeter’s gale is “constantly working to undermine the advantages enjoyed by incumbent firms,” as Powell once observed, big corporations shouldn’t expect protection from scrappy upstarts — and vice versa. Schumpeter’s message to regulators, Powell concluded, is that they should encourage innovation by not encumbering businesspeople with inappropriate rules — in other words, they should think twice before interfering.

This is an idea with big implications. It suggests that as these industries converge, the conglomerates that dominate them should be allowed to consolidate further. In a few years’ time, a handful of survivors could own it all. “Powell tends to say, ‘Let mergers happen,’” says former FCC chief technologist David Farber, who holds a chair in telecommunications systems at the University of Pennsylvania. “But there’s a limit to how much you can say that and still have viable competition. Watching where that line’s drawn is going to be fun.”

AN EX-ARMY OFFICER GIVEN TO PINSTRIPES and pontification, Powell exudes the comfortable air of a business-as-usual executive. Implicit in his approach to his job, however, is an awareness that he comes to it at a time when convergence is fast changing how all these industries are configured. “Regulation is best when markets are mature,” he declares as he settles into an armchair in his office, suspenders peeking out from his navy-blue suit. The room is appropriately expansive, though the location — the top floor of a stubby building in southwest Washington, convenient to an expressway on-ramp but nothing else — testifies to post-Reagan ambivalence about the role of government. “The Bell network was basically the same for 75 years,” he continues. “It’s an engineering marvel, and I don’t mean this disparagingly, but it is tin cans and string at heart. And we understood it. But what do you do when all the cable operators start doing digital telephony? The minute you move to an IP digital architecture, it gets murky.”

The most basic problem Powell faces is that, decades after its founding, the FCC remains mired in the New Deal, with separate bureaucracies and entirely different rules for broadcasting, satellite, cable, telecom, and wireless. His overarching goal is to bring this archaic regulatory structure into the digital age. “Powell arrived with a very clear sense of what the future ought to look like,” says Mike McCurry, former press secretary to President Clinton. “He does not want to see the regulations of telephony and broadcasting superimposed on the new technologies of the 21st century.”

“We’ve got to figure out how to get greater harmony across the regulatory structure,” Powell says, “so consumers aren’t denied some cool new gadget because nobody can figure out how to classify it. Cable modem services — even the courts have said three different things. It’s a telecom service, it’s a cable service, it’s an Internet service. The answer is going to have everything to do with how fast the services appear, how well they work, and how regulated they are. IP telephony? This is the coming storm. Telephony is the most regulated communications sector in America, the Internet is the least. God help you when they’re the same thing.”

So Powell is restructuring the commission, joining satellite, cable, and broadcasting in a single media bureau. But while he’s free to shuffle bureaucrats, he can’t go too far without congressional OK. Though commissioners are appointed by the president, they function as an arm of Congress, implementing and interpreting legislation. Yet within this framework they have a lot of latitude: Congress decided decades ago to put a cap on the percentage of subscribers a cable company can reach, for example, then left it to the FCC to decide what the cap should be.

The FCC chief’s real power is his ability to shape the debate, and here Powell is in a better position to have an impact than anyone in memory. His father is Secretary of State Colin Powell. His chief political benefactor is Arizona senator John McCain, who has a lot of clout on Capitol Hill and sponsored his appointment to the commission in 1997. Powell spent three years as a member of the agency before being named to head it — time enough to learn to navigate the minefields that have disabled some of his predecessors — and his talent for stroking congressional leaders is regarded in Washington with awe. “I’m convinced he’ll be an outstanding chairman,” says McCain. “Not a doubt in my mind.”

Powell’s path to bureaucrat began with a stint in the Army, but his career as a soldier came to an early halt. He was a lieutenant in an armored cavalry division in Germany when the noncom driving his jeep fell asleep on an autobahn and lost control. Powell was thrown out of the vehicle, which then bounced on top of him. After a lengthy recovery, he attended Georgetown University law school, where he studied under Joel Klein, who later became the Justice Department’s antitrust chief under Clinton. Powell earned his degree in 1993, then clerked for Harry Edwards, chief judge of the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit — the court that rules on suits brought against federal regulators. He went on to become Klein’s chief of staff at Justice, where he stayed until Edwards persuaded McCain to push him for an FCC seat in 1997.

“I’m the United States government, the one the Constitution warns against,” says Powell. “The public interest works with letting the market work its magic.”

Powell should have little problem getting his way on more or less straightforward issues, like restructuring the FCC and rethinking current rules. Two of the other commissioners — Kathleen Abernathy, an FCC attorney turned telecom lobbyist, and Kevin Martin, an FCC attorney turned Bush campaign aide — are like-minded Republicans, assuring him a solid majority on the five-member commission. Nor is he likely to run into trouble with the courts, given his experience in Edwards’ chambers. “Michael is very pragmatic,” says Klein, who now heads the US operations of the German media conglomerate Bertelsmann. “His going-in view is that if there aren’t strong factual reasons for the government to intervene, it should stay out. But he doesn’t have a view of the world dictated by theory. The DC Circuit is going to ask tough questions: ‘Where are the relevant facts? What is the basis for judgment?’ One can have a lot of theory, but the adjudicating court is going to look at the facts.”

That’s what happened last March, when the DC Circuit voided the cap on cable ownership on First Amendment grounds. “The minute you stray from economic efficiency and anticompetitive issues, you are talking about message,” Powell says. “That is something I endorse the country debating 100 percent. But I’m the United States government. I am the one the Constitution warns against. And that’s what’s at issue in the DC Circuit — the courts will not issue a blank check to the government to stray into diversity and media without a more informed and substantial basis for doing it.” So Powell created a working group to get the facts. “Every one of these rules has been waived at one time or another. So why are we having food fights inside the Beltway about what will happen? Why aren’t we out there examining what really happened?”

But even if Powell’s study justifies his inclination to revamp the media ownership rules, it won’t get him any closer to his larger goal of updating the entire regulatory structure to acknowledge the reality of convergence. To do that he’d need to persuade Congress to revisit the Telecom Act, and that’s a can of worms no one wants to pop open. “The 1996 Telecommunications Reform Act was neither about telecommunications nor reform,” asserts McCain. “It was all about special interests. You have too much money in campaign contributions, and they offset each other, so we’re in gridlock.” If the same money had been put into delivering broadband, McCain says, “they could have wired every home in America.”

THERE’S ANOTHER REASON POWELL WON’T BE MOVING America’s regulatory structure into the 21st century anytime soon: He’ll be too busy with all the mergers coming up. At the top of his agenda is EchoStar’s $32 billion acquisition of Hughes Electronics, whose DirecTV subsidiary is the only other major satellite television service in the US. Then there’s Comcast’s deal to buy AT&T Broadband. While the Justice Department has primary responsibility for merger reviews, it’s the FCC’s job to decide if mergers are in the public interest — and that’s a concept Powell has a hard time grasping. He once compared the public interest to modern art — “people see in it what they want to see” — before declaring last year that “the public interest works with letting the market work its magic.” Still, he’s not going to sit these cases out: Four days after the Hughes-EchoStar deal was announced, he appointed a committee to review it.

More deals are in the offing, particularly in telecom, where the Bells look like winners. With the startups that sprouted to challenge the Bells dying off, the long distance carriers — AT&T, Sprint, and WorldCom — are left to fight them alone. But brutal price wars and competition from wireless have slashed their profits, and now the Bells are moving in for the kill. The Telecom Act allows them to offer long distance once they can show they’ve opened their local networks to competition — which they’re finally doing, now that most of the newcomers are dead. That means the Bells can bundle local and long distance into one package, an offering the long distance carriers can’t easily match. “Where do we fit in?” says Vonya McCann, Sprint’s chief lobbyist in Washington. “That’s our concern. Are we a niche player? I don’t know.”

Most likely they’ll end up as nice little units of the Bells. Last fall AT&T, having just sold off its wireless unit, broached the idea of selling the rest of itself to BellSouth. BellSouth wasn’t interested, but it did start talking with Sprint. There’s little doubt what will happen next. “In the next 12 to 18 months there’s going to be a massive and historic consolidation,” says Blair Levin, who served as Reed Hundt’s chief of staff at the FCC and is now an analyst at the investment bank Legg Mason. “The Bells are going to end up owning most of the critical assets of the long distance carriers” — not just the long distance business, but their Internet backbone. “The math is pretty simple.”

At this point, some telecom mergers might be a good thing. Clayton Christensen, the Harvard management guru who wrote The Innovator’s Dilemma, argues that until emerging technologies like broadband mature, we need big corporations that can supply every piece of the puzzle, as IBM did with computers in the ’50s. “When you’re using new and poorly understood technology,” he says, “you have to do everything in order to do anything.” By pushing for an end to wireless spectrum caps, Powell has encouraged mergers among the six competing carriers — mergers that should allow the survivors to get better terms from equipment and handset suppliers, develop more appealing mobile Internet services, and move more quickly to third-generation networks. Christensen says the same principle applies to DSL, the technology that converts voice lines into high-speed Internet connections: “NorthPoint” — a now-defunct DSL provider — “tries to plug into the Bell infrastructure, but even if the people who run Verizon were perfect Boy Scouts, it’s not possible. Regulation cannot decouple an industry where the product is not yet good enough.”

This runs counter to the thinking behind the ’96 Telecom Act, which the FCC interpreted under Hundt to benefit the startups that were making a run at the Bells. Powell isn’t prepared to abandon the goals of the Telecom Act outright, but he does wonder why anyone would expect the Bells to give up without a fight. “A hundred years of legacy monopoly wasn’t going to be magically unraveled in five years,” he says. “I genuinely believe that in more realistic time frames — 10 years, 15 years, 20 years — this country’s telecom market will be more competitive than any in the world, because technology is relentlessly improving. But it never happens on some beautiful, straight-line trajectory. The telegraph didn’t happen that way, electricity didn’t happen that way, television didn’t happen that way. I’m an old tank soldier. I think some things are just dirty and messy, and this is one of them.”

The logic of convergence suggests that the consolidation trend won’t stop with telecom. In the US, media conglomerates looking for distribution have rarely ventured beyond the obvious — broadcasting stations, television networks, and cable systems. But Jerry Levin, the outgoing CEO of AOL Time Warner, recently predicted at a breakfast discussion in New York that media conglomerates and telcos will eventually decide they belong together. This is already occurring in Europe; one of the biggest proponents is Vivendi Universal, which owns a leading French wireless carrier and has partnered with Vodafone, the world’s largest wireless company, to set up a pan-European Internet portal. “I was not expecting such a strong endorsement of our strategy from the CEO of AOL Time Warner,” quips Vivendi’s Messier, who also spoke at the event.

A handful of media-telco combinations were tried and abandoned in the US in the mid-’90s — ost notably Tele-TV, a consortium set up to develop programming the Bells could distribute once they’d perfected DSL or replaced their antiquated copper lines with high-speed fiber. The telco execs were good for a few laughs in Hollywood, but what really doomed Tele-TV was the ’96 Telecom Act, which promised the Bells the chance to get into long distance. “It became clear that it would be easier to generate profits from long distance than to spend the money to upgrade the telephone lines,” says Sony Corp. of America chair and CEO Howard Stringer, who headed Tele-TV at the time. “I think ultimately wireless is the way to go.”

“I’m an old tank soldier. I think some things are just dirty and messy, and telecom is one of them.”

Telcos today are hamstrung: “They need to invest so much money in upgrading their networks that they have no flexibility,” says Messier. “But they will definitely need to be supplied with content” — as NTT DoCoMo’s wireless i-mode service in Japan is supplied by the likes of Sony, Bandai, and Disney. Meanwhile, content companies need distribution — and there’s nothing better than having a line, be it telephone or cable, into the consumer’s home. That gives them a direct billing relationship with the customer; it also gives them leverage against the competition.

If you’re a media mogul, and a key distribution pipeline is owned by a competitor, you want to own an equally critical pipeline so you’ll have some bargaining chips when it’s time to talk access. Otherwise, bad things can happen. Two years ago, while the government was reviewing the AOL-Time Warner merger, Time Warner Cable and Disney’s ABC network were having trouble coming to terms on a new contract — so Time Warner simply yanked ABC off the system. “They pulled our signal on midnight Sunday,” recalls Disney lobbyist Preston Padden, “and on Tuesday morning The New York Times ran a picture of a group of nuns who’d gathered to watch Who Wants to Be a Millionaire — and they were all crying. I knew then we were going to win. You can’t do better than nuns crying in the Times.”

ABC got back on Time Warner Cable in short order, but the lesson was not lost on anyone: Distribution means power. Seagram CEO Edgar Bronfman Jr. had already concluded that his Universal entertainment subsidiary needed pipe; within weeks, he sold the whole company to Vivendi. Then Viacom bought CBS — the network, the TV stations, the radio stations, the works. “Consolidation always justifies consolidation,” declares Blair Levin of Legg Mason. “I’d feel better if I had a sense of how these companies are going to compete with one another and not simply divide the markets.”

THAT’S WHERE THE FACTS GIVE OUT and the faith kicks in. Ultimately, this is what Powell’s views rest on — his faith in technology’s ability to fuel the process of creative destruction. In the digital world, says Powell, “everything can grow fast. Everything has network effects. And there is not a business out there that isn’t trying to capture the market. So how are you going to respond? Are you going to apply the classic anticompetitive overlay and say, ‘Let’s drop the hammer’? Schumpeter teaches that what you’re observing could be nothing more than a new innovator who is on top maybe for only a moment, or who is on top because he deserves to be, because he took risks and did it. If that’s the case, government should be much more reluctant to dislocate his company from its naturally won advantage.”

Not that anyone would mistake the corporate giants that dominate media and telecom for innovators. The list of missed opportunities is endless: Broadcasters got free spectrum to go digital but have left it untouched for years; interactive television, long a reality in Europe, remains a visionary concept in the US; wireless carriers are still trying to figure out how to make a go of the mobile Internet without moving to Japan. Given past behavior, are the titans of the communications industry more likely to fight the future than move us toward it? “I have the same concern,” says Powell. “But I demand better reasons to take action than just, you can articulate a set of speculative horribles that might happen.”

Meanwhile, out there beyond the corporate walls, the innovations have kept coming. Network viewership has been dwindling for years, thanks to the introduction of cable and satellite. Television as we know it is threatened by personal video recorders that can bypass advertising and make time slots irrelevant. And though the recording companies have beaten back the free-music bogeyman with a massive legal onslaught, they’re still struggling to get out of shrink-wrap. In New York and Hollywood, fear is palpable: The news and entertainment industries of the 20th century are in danger of being creatively destroyed. “You can’t rest on your laurels at all,” says Stringer, the Sony exec. “The quo will lose its status instantaneously in the brave new world that Michael Powell is talking about. It creates a permanent anxiety, which is why many of these mergers take place. You protect yourself against the dark stranger around the corner — and you hope he’s put off by your size.”

There’s another factor at work, too. “A lot of the acquisition frenzy is really driven by the mathematical need to grow,” says Clayton Christensen. “You can’t forecast down revenues — that’s not acceptable. And yet growth is like a heroin addiction — there were things that satisfied your addiction when you were little, but once you’ve merged you need twice the kick.” Big companies aren’t looking for little scores, even if they might become big scores later on — which is why innovations so often come from outside.

Nonetheless, Powell believes. “When my 12-year-old is 22, I think he’s gonna look out and see an absolutely wonderful communications environment,” he declares, his voice turning rosy. “And where do I get that optimism? No matter what the failings of particular businesses or the government, technology is relentlessly improving. That is a wild card that can’t be altered. This stuff keeps changing the world, and I believe there are enough entrepreneurs left in America that some of them are going to emerge from a basement or a garage, given half the chance, and harness it.”

In Schumpeter’s world, anything can happen — as, in fact, some of the issues on Powell’s docket attest. AOL Time Warner may threaten its competitors in dangerous new ways, and like any company it could turn complacent and stodgy. But the fact remains that a scrappy little online startup from the DC suburbs has taken over the world’s most powerful media empire. That’s the kind of upset Powell is betting will keep happening again and again.■

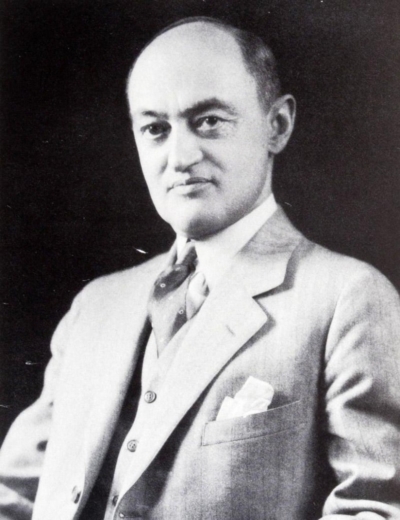

The Father of Creative Destruction

Why Joseph Schumpeter is suddenly all the rage in Washington

ADAM SMITH, MAKE ROOM: Joseph Schumpeter has come to Washington. Capital policy wonks may not yet be wearing Schumpeter ties, but the Harvard economist’s ideas are cited by everyone from Federal Reserve chief Alan Greenspan to the warring parties in the Microsoft antitrust case.

ADAM SMITH, MAKE ROOM: Joseph Schumpeter has come to Washington. Capital policy wonks may not yet be wearing Schumpeter ties, but the Harvard economist’s ideas are cited by everyone from Federal Reserve chief Alan Greenspan to the warring parties in the Microsoft antitrust case.

Schumpeter (1883-1950) argued that capitalism exists in the state of ferment he dubbed “creative destruction,” with spurts of innovation destroying established enterprises and yielding new ones. This view seems far more current than Smith’s Newtonian notion of an “invisible hand” generating stability in the marketplace.

Smith was a conceptual breakthrough for Europe, but he didn’t say much about bone-jarring technological shifts or the crucial role of entrepreneurship. “It’s not difficult to be for Adam Smith and Joseph Schumpeter at the same time,” maintains House majority leader Dick Armey. “The market must clean itself out by taking resources away from the losers, so it creatively destroys the losing companies and reallocates resources to the winning companies. That’s really what’s going on.”

Schumpeter, who came of age in the Vienna of Sigmund Freud, once declared his ambition to become Europe’s greatest lover and greatest horseman, “and perhaps also its greatest economist.” (Later he said coyly he’d achieved two out of three.) In 1932, he left Europe for Harvard. There he argued that it’s entrepreneurs who drive economies, generating growth and, through successes and failures, setting business cycles in motion — a provocative claim in the ’30s, when capitalism seemed bankrupt. Even after publishing his landmark Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy in 1942, Schumpeter was overshadowed by John Maynard Keynes, who preached government spending as a way out of the Depression. “Schumpeter probably was right all along,” says Michael Powell, “but it’s only now, at Moore’s law speed, that you can actually observe it.”

“Schumpeter was probably right all along. But it’s only now, at Moore’s Law speed, that you can actually observe it.”

March 10, 2002

March 10, 2002