Not long after Edgar Bronfman Jr. sold Universal to Vivendi in a panic over distribution, the company collapsed amid overwhelming debt and allegations of fraud. CEO Jean-Marie Messier was forced out, and Barry Diller ended up running the place. if Messier was a self-styled “visionary,” Diller wanted no part of such grandiosity.

Diller benefitted greatly from the rise of Vivendi’s “visionary” Jean-Marie Messier. He may gain even more from Messier’s fall.

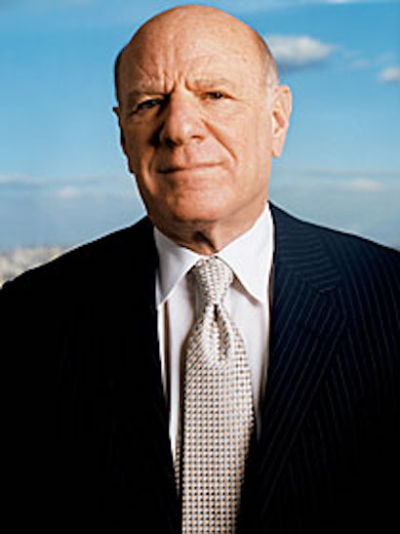

BARRY DILLER IS NOT a guy you should try to bullshit. Media mogul, e-commerce czar, former Hollywood studio chief, he’s quick to dismiss a harebrained scheme when he sees one. Diller lived up to his reputation on a trip to Paris last July in his new role as chief of Universal, the American entertainment arm of Jean-Marie Messier’s global media empire. Messier had formed Vivendi Universal in a blizzard of deal-making two years earlier, and now the Euro-American colossus was collapsing in a cloud of debt and recrimination. Diller and all the company’s division heads were meeting in Paris to present themselves to the new CEO, Jean-René Fourtou, who stepped in after Messier got the shove. One of the divisions was Vivendi Universal Net, the Internet unit that was supposed to be Messier’s answer to AOL.

In Messier’s vision, VUNet was to have been critical to the entire enterprise, carrying Vivendi Universal content — music, movies, games, TV shows — to consumers around the globe. But if AOL had turned out to be troubled, VUNet was worse: an outfit plagued by mismanagement, confusion, and cost overruns, sucking money from a company facing $33 billion in debt and no apparent means to repay it. Fourtou was a pharmaceuticals executive with zero experience in either entertainment or the Internet, but Diller, his go-to guy in the US, had made a name for himself in both. So when the head of VUNet started describing projects her team was working on — projects she claimed were critical to the future of publishing, music, and motion pictures — Diller interrupted her and turned to the heads of those divisions for confirmation.

Movies? It’s all news to me, said studio chief Ron Meyer.

I don’t know anything about any projects, said music chief Doug Morris.

I don’t know anything about any projects, said music chief Doug Morris.

If it was really important, replied publishing head Agnès Touraine, we’d be doing it ourselves.

The VUNet chief tried to defend herself, but Diller wasn’t having it. “Oh, please,” he said, cutting her off with the classic George Burns line. “Say good-night, Gracie.”

It was a pivotal moment for VUNet, indeed for the whole idea of media over the Internet. “‘Shut it down’ — that was my recommendation,” Diller recalls six months later, sitting in a small but exquisitely appointed conference room in his New York office. And in fact, not long after the meeting, Fourtou announced that Internet ventures were not a core business and would either be sold or integrated into the rest of the company.

A Decade of Reporting on the Global Media Conglomerates |

In the 1990s and into the 2000s, a series of ego-fueled mega-mergers led to the creation of six global media conglomerates: News Corp., Sony, AOL Time Warner, Vivendi Universal, Viacom and Walt Disney. For most, it would not end well. |

Can the PS3 Save Sony?The company that created the transistor radio and the Walkman is at the precipice.

|

Barry Diller Has No Vision for the Future of the InternetThat’s why the no-nonsense honcho of Home Shopping Network and Universal is poised to rule the interactive world.

|

The Civil War Inside SonySony Music wants to entertain you. Sony Electronics wants to equip you. Too bad their interests are diametrically opposed.

|

Big Media or BustAs consolidation sweeps the content and telecom industries, FCC Chairman Michael Powell has a plan: Let’s roll.

|

Vivendi’s High Wireless ActWill a global media company with continent-wide mobile distribution prove unbeatable?

|

Reminder to Steve Case: Confiscate the Long KnivesTime Warner brings fat pipe and petabytes of content to AOL—plus a long history of infighting and backstabbing.

|

TV or Not TVRupert Murdoch aims to capture Europe’s interactive TV market with a Sun set-top strategy. But a growing Microsoft alliance has different plans.

|

Think Globally, Script LocallyAmerican pop culture was going to conquer the world — but now local content is becoming king.

|

Edgar Bronfman Actually Has a Strategy—with a TwistThe Seagram heir is challenging Disney in theme parks and spending billions to be No. 1 in music. Can this work?

|

There’s No Business Like Show BusinessA handful of powerful CEOs are battling for the hearts, minds, and eyeballs of the world’s six billion people.

|

What Ever Happened to Michael Ovitz?Striving to make his comeback, CAA’s superagent is now an unemployment statistic. Seven lessons to be learned from the fall of the image king.

|

Can Disney Tame 42nd Street?Disney is pouring millions into one of Manhattan’s most crime-ridden blocks. What does Michael Eisner know that you don’t?

|

Twilight of the Last MogulLew Wasserman has been shaking Hollywood since the ’30s. When Seagram bought MCA, was he really out of the loop, or was he king of the dealmakers to the last?Los Angeles Times Magazine | May 21, 1995 |

Diller is a man with little patience for futuristic distribution schemes or fantasies about Internet dominance. He sees the Net as a medium for buying and selling. As CEO of USA Interactive — an amalgam of e-commerce vehicles he’s built up over a decade and still runs as his “day job” — he’s prospered online like few others. Last year, he also took charge of Universal, thanks to a convoluted deal that turned it into a joint venture between USAi and VU. Now Universal, like most of the properties Messier assembled, is up for grabs as Fourtou jettisons assets to raise cash, and Diller has been among the front-runners to take control.

Diller and Messier could hardly be more different. If Messier personified the overreaching ambition that gave us Vivendi Universal and AOL Time Warner, Diller is about succeeding in a real-world environment. Messier piled on debt as he ricocheted from one multibillion-dollar acquisition to the next; USAi is flush with cash. Messier fell for flashy non-businesses like MP3.com; Diller bought functioning companies — Ticketmaster, Expedia, Hotel Reservations Network — that had sound business plans and were either already online or naturals to go there. And where Messier embraced the role of visionary, Diller professes embarrassment that people would actually call him such a thing. “The first time they said it,” he maintains, all but cringing in USAi’s New York headquarters, “I thought they were talking about eye charts. I don’t see anything full-blown. I never have. I see what interests me.”

At 60, Barry Diller is compact and powerfully built, his figure taut and trim. His tie is tightly knotted, his shirt unwrinkled. The notepads and coasters on the table are lined up with military precision; the 19th-century map of the US on his wall suggests a cartographer’s love of detail. The terrace outside, with its panoramic views of the Hudson River and Central Park, is a slice of English garden perched dizzily atop the world. It’s been more than a decade since Diller walked away from Hollywood, but his life doesn’t lack for glamour: This evening he and his wife, the designer Diane von Furstenberg, will be hosting the opening-night party at the Winter Antiques Show, the Park Avenue extravaganza that kicks off the city’s social season. Meanwhile, he follows his interests. They’ve led him to Universal, to a conglomerate that has been in limbo for nearly a year since the eclipse of the biggest, most Napoleonic vision of all. Diller profited greatly from Messier’s rise, and he’s poised to gain even more from Messier’s fall. In a time of staggering write-downs, plummeting stock prices, and desperate attempts to raise cash, he stands out as a mogul for the post-visionary age.

WITH THE BUST IN INTERNET STOCKS, there are fewer than a dozen people left on the Forbes 400 list whose money comes from the Web. Diller is one of them. USA Interactive has a market valuation of some $12.5 billion, putting it a distant second to eBay ($22 billion) but above Yahoo! ($10 billion) and Amazon ($8 billion). It has 26,000 employees in 26 countries and projected revenue this year of $6 billion — and it’s controlled by Diller alone. Of course, it’s not a pure Web play: TV shopping accounts for about 40 percent of its revenue, while the rest is a combination of online and phone sales of concert, sports, and airline tickets, hotel reservations, and the like. But to Diller, the point is that it’s all interactive. Who cares if some customers are Web surfers and others are couch potatoes wielding telephones?

Dotcom survivors are rare enough; the number of media moguls who’ve become dotcom survivors is small indeed. Diller was running 20th Century Fox for Rupert Murdoch in the 1980s when he started the Fox television network, which broke the grip the Big Three had on broadcasting. Then he left Hollywood and bought QVC, the déclassé TV channel best known to aficionados of cubic zirconia. That was the genesis of USAi.

What motivated him was an epiphany. “I use that word to describe only that experience, no other,” Diller says. “That would cheapen the word.” It came in 1992, after he’d quit Fox and set off on a now-legendary road trip across the US, seeking to learn every aspect of the communications business. It wasn’t your ordinary road trip: People in Hollywood say he had his Gulfstream jet swoop down for him every Friday afternoon wherever he happened to be and whisk him off to the coast for the weekend.

But there, in the suburban Philadelphia studios of QVC, he had a flash.

“I, on the selling floor of QVC, saw primitive convergence,” he declares. “Telephones, television sets, computers. I watched a little screen and when there were a lot of phone calls, a lot of transactions taking place, the bars would rise, and then they would recede. It was like waves. It was a kind of wild experience. I thought, this is going to change things. I did not know how or where or why, but I knew that interactivity at scale, which was what I was watching, was going to be powerful.”

A few weeks later he went back to Philadelphia for a meeting with Brian Roberts, the president of Comcast, who mentioned that his company owned 14 percent of QVC. “I said, ‘Wow — connection!’” Diller recalls, “and he said the founder of QVC wanted to retire — serendipity! And I bought his interest.” Comcast later took over QVC, but Diller bought the Home Shopping Network in its place, and then he kept buying. “The course of my life has been curiosity and serendipity,” he says. “I didn’t have a single thought in my head other than, I don’t know what this is, but I’m fascinated by it and I want to learn it. Learning it taught me things. It taught me that interactivity, the Internet, allowed scale and leverage. The next thing that came up was Ticketmaster, which had scale and leverage properties that I recognized. I made a relationship between the two in my mind, and then we acquired. But all of it was opportunistic. None of it was strategic.”

Most of Diller’s businesses today involve selling things through some combination of electronic media — TV, telephone, and, increasingly, the Internet. HSN has given rise to HSN.com. Ticketmaster was doing less than 5 percent of its business online when he bought it in 1997; now it gets 45 percent of its sales through the Web. Moving online makes it both cheaper to operate and more convenient to use: Who wouldn’t rather buy tickets on a computer, where you can look at seating charts and won’t be put on hold? It also provides special opportunities, like the ability to create a resale market so ticket holders can find ticket seekers.

The one part of USAi that doesn’t involve commerce is the online guide Citysearch. Meant to be an adjunct to Ticketmaster — once you buy tickets you need to find a restaurant, right? — it’s succeeded mainly in losing money. But it did lead to the acquisition of Match.com, which has become the Web’s number-one personals site and the source of USAi’s fastest-growing revenue stream. The possibilities are “kind of endless,” says John Pleasants, who heads the division that includes Match.com. “It’s how many people there are on the planet. How much would you pay to find your spouse?”

The idea of going into online dating came out of a meeting in which Diller and Pleasants were talking about what was wrong with Citysearch — a static information repository, not enough people going to it, no way for them to connect bingo! Such discussions can be chancy: Just ask the TV exec who had a section of his wall framed after Diller hurled a videotape into it. People who work for Diller know to be thoroughly prepared, able to defend their positions, and, when all else fails, ready to duck. When things go well, however, Diller’s method can be quite rewarding. “He’s very Socratic,” says Pleasants, “very inquisitive. He likes to poke at things. People say he’s picking up on random details, like the color of a Web page, but in fact he’s scratching. He’s trying to find the essence of things all the time.”

To Diller, the point is that it’s all interactive. Who cares if some customers are Web surfers and others are old-fashioned couch potatoes?

Diller’s rigorous approach is one thing that kept him from being a dotcom fashion victim, but his real secret was his stubborn refusal to overpay. In 1999, at the height of the mania for Web portals, he attempted to buy Lycos for some $6 billion in stock — a mere 2 percent premium over its market valuation — shortly after @Home had bought Excite for a whopping 78 percent premium. That was unacceptable to Internet entrepreneur and Lycos board member David Wetherell. He led a shareholder revolt, blasting Diller as an “old media” guy who “doesn’t get it.” Never one to hold back, Diller accused Wetherell of “stock manipulation games and duplicity” before withdrawing his offer. His insistence that Lycos was worth only what he wanted to pay began to undermine all Internet stocks: What if they were wildly overvalued? The market recovered, but it was a fool’s run-up; a year later, the long slide began.

Excite@Home is now out of business. Stock in Wetherell’s company, CMGI, has fallen from $45 (adjusted for splits) to under $1. As for Lycos, a Web company controlled by Spain’s Telefonica laid out $12.5 billion in stock to buy it — though when the sale closed, the stock was worth barely a third of that. Diller has since decided he’s better off without Lycos anyway. “We have too much audience now to have particular use for a portal,” he maintains. And while owning Lycos would have guaranteed his e-commerce ventures a place on the Web, it would only have complicated relations with AOL, Yahoo!, or MSN. From this he drew an important lesson, one with implications for Universal as well: “Being Switzerland, which is a friend to all, is a better policy for USAi than anything else.”

Crash of the TitansDiller’s rise comes amid a shakeout in the battered global media arena, where the ranks of the supermoguls are thinning.▸ Michael Eisner, Walt DisneyPeople said he was “more Walt than Walt.” Then he bought ABC to marry content with pipe, and the downhill slide began.▸ Nobuyuki Idei, SonyHis grand ambition is to get content to work with hardware—at a time when they’ve never been more at odds.▸ Jerry Levin, AOL Time WarnerMerging Time Inc. and Warner didn’t work, so Levin bought Turner. That didn’t work, so he sold it all to AOL. Now he’s history.▸ Jean-Marie Messier, Vivendi UniversalHe built the world’s first transatlantic communications colossus with Internet aspirations. Too bad he couldn’t pay for it.▸ Rupert Murdoch, News Corp.He owns sensational tabloids, a Hollywood studio, and a satellite empire that will circle the globe—if he wins DirecTV.▸ Sumner Redstone, ViacomParamount, CBS, MTV: What other septuagenarian tycoon could have given us The Osbournes and Jackass: The Movie? |

IT WAS A 1997 MEETING WITH HIS FRIEND Edgar Bronfman Jr. that brought Diller into Universal. The company was owned by Seagram, and Bronfman, the parent firm’s CEO, wanted money to increase his share of the music business. So he sold the TV division to Diller in exchange for $1.3 billion in cash and nearly half of Diller’s company, a deal worth $4.3 billion in all. Diller talks about “the interactive part of me” and “the entertainment part of me,” and since leaving Fox he’d embraced both. But with the Bronfman deal, he seemed to be trying to build a TV empire. He already owned HSN and a chain of UHF TV stations (since sold), and now he was getting two cable channels, USA and the Sci-Fi Channel, plus the unit that produces Law & Order and other shows. But he ended up with far more than he bargained for — because this was the deal that, thanks to the law of unintended consequences, set him up to be running Universal today.

After Vivendi acquired Universal, Messier decided he wanted television back in the fold, and in December 2001 he paid Diller $10.3 billion to get it. But Messier made a serious faux pas at the press conference announcing the pact, when he used the occasion to declare the idea of corporate subsidies for French film production “dead,” sending Paris pundits into an uproar. There were at least three problems with his scheme to build a transatlantic media empire, and this was the tip-off to one of them: Temperamentally, he lacked the sensitivity to promote the kind of globalism he espoused. A bigger problem was financial: The $33 billion in debt he ran up threatened Vivendi’s liquidity and ultimately triggered his ouster. The third was technological: In his attempt to secure distribution not just through cable and satellite but through wireless networks and the Internet, he was a classic victim of the syndrome one ex-Universal exec calls “premature technology arousal.”

Could Messier’s vision have worked? “Yeah, conceptually,” says Diller. “But you need a very firm rug underneath you, and the rug was not firm. Someday — maybe not this decade or even the next — it will be a perfectly reasonable equation. But almost all of it was premature. Certainly wireless — my God! We don’t have an efficient, fat, wired pipe yet.”

“I’m not sure it was a failure in concept,” agrees Diller’s friend Herbert Allen, the New York investment banker and adviser to the media baron set. “It was a failure in profitability. You can’t buy a house you can’t afford, and he couldn’t buy companies he couldn’t afford. The economics fell apart before the concept got tested.”

Of course, paying Diller $10.3 billion for television was one reason the economics fell apart. “There was no need to buy it,” declares an executive close to the transaction. “Vivendi had a direct line of control. Nobody else could buy it without buying them out first.” But buy it he did — and Messier was so eager to do so that he gave Diller extraordinary leverage over Vivendi’s future. Universal’s film, television, and theme park businesses became a joint venture between Vivendi and USAi, with Diller as its CEO — and Vivendi has to pay USAi $1 billion to $2 billion (depending on who’s reading the agreement) if those operations are disposed of in a way that leaves USAi owing taxes. This gives Diller veto power over any move to unwind the partnership, at a time when Fourtou, the new CEO, is desperate to raise cash. “Any direction Fourtou wants to move in, he has to go through the office of Barry Diller,” says Harold Vogel, one of Wall Street’s senior media analysts. “And Diller will exact a toll for that passage.”

Power and money, money and power — that’s what Hollywood and Wall Street say Diller’s all about. “Look,” Diller says abruptly. “I’ve been shockingly lucky — but the money is a byproduct. It’s not that I don’t think it’s nice, but it’s never been a motivating factor in my life. I’m propelled by curiosity. Honestly. That’s” — he pauses, looking deeply pained — “all I know.”

Ever since Diller took up his post at Universal, the parking lot has been emptying out at the spacious San Diego campus of VUNet USA. This is the Web operation Messier was building around MP3.com, which he bought in 2001 for $372 million. The survivors seem vaguely lost amid the earnest corporate wackiness of their Day-Glo walls and wavy-topped cubicles, but at least they’ve fared better than their compatriots at Vizzavi, the European wireless portal that was unloaded onto Vodafone. “I thought the idea to become one of the first digital distributors in the world was very exciting,” says CTO Patrick de Moustier, a black-clad engineer who came over from Paris. “But a lot of things have changed” — the collapse of online advertising, for example. “I’m still convinced it’s possible to make money with the Internet,” he adds hopefully. “The proof is Barry Diller and USAi.”

But Diller’s approach to the Internet is diametrically opposed to Messier’s. First, he rejects the idea of a separate unit handling Internet distribution for all of Universal: “I don’t think it makes sense to hire a bunch of IPers, either Internet Protocolites or intellectual propertyites, and put them in a room and say, ‘Go figure out what this should be.’” Far better to put them in a room with people who actually know the entertainment business. Second, as he realized after losing Lycos, owning a distribution channel can create more problems than it solves — it complicates your relationship with other Internet distributors, and it doesn’t satisfy consumers’ demand for content from your competitors. And finally, he doesn’t think much of the idea of distributing content on the Internet anyway — at least, not at this stage in the Net’s development.

“What is content?” he asks, turning literal-minded as he sets his palms a few inches apart, as if to make a box. “Content is that which resides between two sides or four sides. But in Internet terms, when you talk about content, what you’re really talking about are goods and services — the selling of goods or the dissemination of services. That’s what interactivity is. I think Match.com is a really creative interactive service, but I would never call it content, because for me, content is narrative. Look — you can think of the Internet as just a distribution platform, and in that regard it will at some point be the major distribution platform in the world. But it is not of any particular current interest for video, because it does not yet have the bandwidth necessary.”

The most obviously interactive form of entertainment at Universal has been games — a division Fourtou was busy trying to sell all winter. Assembled in a series of acquisitions by Messier, the games division started small but has been growing fast, from about $300 million in annual revenue two years ago to nearly $1 billion today. It’s planning to go online with multiplayer titles based on Lord of the Rings books and on Marvel Comics superheroes. On June 20 it will release The Hulk, a game version of the Ang Lee movie that Universal Pictures will open the same day. As with The Matrix, game and movie were developed in tandem, with a consistent look and feel and cues embedded in the film to give savvy game players in the audience an edge. There’s already a Hulk ride at the company’s Orlando theme park, and there will also be a soundtrack featuring Universal artists. “When you have a simultaneous launch that’s global,” says games chief Ken Cron, “the amount of buzz you get really allows you to create a worldwide brand.”

Diller sees the parks as key to all this. If things go according to plan, he says, “within five years you’ll have upwards of 60 million people all over the world coming to the parks. Think about that. In the parks, they are your captives. If you give them a bad experience, they won’t be hostage for any longer than it takes them to get out of the place. But in that environment you can make powerful relationships with people. You can!” So powerful, he argues, that Universal could actually stand for something, the way Fox TV came to mean hip and young when he created it in the ’80s, long before the WB appeared.

“Look,” he asks, “what is the template for this business? The genius of Walt Disney in the ’50s. The control he imposed once you were inside his borders formed the, the, the thing that became the Disney brand. It wasn’t that they made movies, because everybody made movies. Today it is possible, without kicking the can too far in front of you, to say that Universal movies, music, games, and parks provide adult, somewhat edgy entertainment. The Hulk and Eminem and the movie The Fast and the Furious and the Dueling Dragons ride in Florida — they’re not iterations of one idea, they’re four ideas that, if you pull them together inside your park, may form in a consumer’s mind an experience.”

An Eminem ride?

“No, no, no, don’t misunderstand,” he says, stress-testing an Evian bottle in his excitement. “These are not all rides. But there is a place for music in a park” — just as there’s a place for entertainment based on games and movies. In Diller’s scheme, the parks become the crucible in which everything — the interactive and the narrative, the virtual and the real — combines to form a unique identity. “That’s the ambition,” he says. “Whether it will succeed or is practical is currently unknown. But that is the ambition for a company called Universal Entertainment.”

“Even Barry would tell you no one quite knows where all this is going,” says Universal Studios chief Ron Meyer

April 1, 2003

April 1, 2003