FOR BROADCAST TELEVISION, COKE WAS IT. The 50-year partnership of fizzy sugar water and network TV yielded some memorable moments, from the groovy “Things Go Better with Coke” spots of the ’60s to the carefree “Can’t Beat the Feeling” campaign of the ’80s. But in recent years, the 19th-century elixir hit a rough patch in its relationship with TV. Since the big broadcast networks no longer deliver the mass audience the company needs, Coca-Cola cut its network ad spending last year by 10 percent. “Where are we going?” Coke’s then-president, Steven Heyer, asked rhetorically at an Advertising Age conference in 2003. “Away from broadcast TV as the anchor medium.” Acknowledging that many in the ad industry are afraid to follow, he added bluntly, “Fear will subside, or the fearful will lose their jobs. And if a new model isn’t developed, the old one will simply collapse.”

Heyer’s speech was bold stuff when he made it, but lately this kind of television-bashing has become a staple of industry confabs. “There must be — and is — life beyond the 30-second TV spot,” Procter & Gamble’s global marketing officer declared last winter. “Used to be, TV was the answer,” proclaimed the president of GM North America. “The only problem is that it stopped working sometime around 1987.” The broadcast networks have been losing audience share for years, thanks to the remote control, TiVo, and all the new channels on cable and satellite. But when Nielsen Media Research announced last fall that young males — the hardest-to-reach and most intensely targeted subset of humans in North America — were watching 12 percent less prime-time network TV than the year before, Madison Avenue went on orange alert. True, the falloff was only 26 minutes a week — but in the ad business, a few lost minutes can add up to major trauma.

Heyer’s speech was bold stuff when he made it, but lately this kind of television-bashing has become a staple of industry confabs. “There must be — and is — life beyond the 30-second TV spot,” Procter & Gamble’s global marketing officer declared last winter. “Used to be, TV was the answer,” proclaimed the president of GM North America. “The only problem is that it stopped working sometime around 1987.” The broadcast networks have been losing audience share for years, thanks to the remote control, TiVo, and all the new channels on cable and satellite. But when Nielsen Media Research announced last fall that young males — the hardest-to-reach and most intensely targeted subset of humans in North America — were watching 12 percent less prime-time network TV than the year before, Madison Avenue went on orange alert. True, the falloff was only 26 minutes a week — but in the ad business, a few lost minutes can add up to major trauma.

“It’s not that men 18 to 34 have stopped watching TV,” explains David Raines, the Coke VP in charge of divvying up ad money. “But they’re doing a lot of other stuff, too” — going online, watching DVDs, playing videogames. “The bottom line is, ad dollars will follow the consumer.” Last year, substituting product placements for traditional commercials, Coca-Cola followed them into The Matrix Reloaded and Atari’s Enter the Matrix videogame. P&G and GM, the biggest advertisers in the US, tried similar tactics. So while the networks’ ad take for 2003 was flat at $20 billion, Rishad Tobaccowala, chief of new media at the giant buying and planning agency Starcom MediaVest Group, projects that 15 percent of those ad sales could dry up within three years, taking with them as much as $3 billion a year in lost revenue.

“l mean, I resent commercials,” says a 30-year-old ad exec. “They make me push three buttons on my TiVo.”

Network executives freaked at the Nielsen news, but not everyone was surprised. In the five years that Jeffrey Cole has been running the UCLA Internet Project, he’s found that Net users consistently watch less TV than other people — in 2003, more than five hours less per week. This pattern has held for every age group, for both sexes, and in every country he’s studied, from Hungary to South Korea. Young men are simply the advance guard. “Broadcasters used to say, Internet users are different,” says Cole. “But we show that as you go online, you watch less television.” Last year, when Cole did a quick survey of people who do watch TV, he found that only 5 percent of them actually paid attention to the ads anyway. “The business model of television, which is to deliver viewers to advertisers,” he declares, “is as troubled as that of the music industry.”

Eager to reach the disappearing guy demo, marketers are experimenting with advertorial blogs, commercials that pop up in email, even human billboards running around Times Square with ad slogans pasted on their foreheads. Ad revenue to Web sites is soaring, and game publishers are hoping to hit pay dirt as well. For anyone who gets it right, big rewards are in the offing.

Gone in 30 Seconds |

|

Starcom has been planning for this day since 1998, when Tobaccowala noticed that many of his new hires were taking time off to get broadband installed at home. They weren’t about to go back to dialup after college, not when they spent more time online than watching TV. Last February, Starcom was named Ad Age’s media agency of the year after winning the $350 million Coca-Cola account. Now the agency delivers ad messages not just online but through mobile phones, videogames, and word of mouth as well — the new new media. The idea is to keep up with the 18-to-34 crowd by moving beyond 30-second TV spots toward a more direct multimedia entertainment-and-branding experience. “People don’t have to listen to you anymore, and they won’t,” declares Tim Harris, the 30-year-old co-chief of Starcom’s new videogame operation. “I mean, I resent commercials — they make me push three buttons on my TiVo.”

IN A CONFERENCE ROOM at the Beverly Hills headquarters of Creative Artists Agency, whose clients range from P&G to the Farrelly brothers, 10 young men are seated around a massive table, offering up opinions like pearls on velvet. Videogames are great because they make you a participant, not just a viewer. TV sucks — but most of them watch it anyway. And ads?

“I feel manipulated and angry,” says Lee, a 33-year-old musician. “Having these things forced down my throat all the time — especially with network television, it’s loud, it’s brash.”

“Now that I have TiVo, I realize how much of TV is actually commercials,” says Nick, a 25-year-old marine biologist. “I can watch two shows in almost the time it took me to watch one. Then if I see a commercial I like, I’ll go back to it.”

“I don’t think they hate ads,” concludes the session’s moderator, Jane Buckingham, who heads CAA’s Youth Intelligence unit. “They hate bad ads. If it’s a cool ad, they’re going to watch it.”

Take the Quiznos Spongmonkeys. Created by Joel Veitch, a London-based Web and TV producer who specializes in hilariously asinine Flash animations, the Spongmonkeys are almost certainly the first cartoon rodents to be enlisted in a fast-food campaign. The spots — which show one of the razor-toothed, demented-looking furballs strumming a guitar while the other screeches a paean to Quiznos (“We love the subs! ’Cuz they are good to us”) — became an instant sensation when they debuted in February. Viewers either loved them or thought they were the most revolting thing they’d seen since, well, since the last batch from Quiznos, one of which showed a guy in a business suit sucking a wolf’s teat.

The lessons for Madison Avenue are clear. If you want to capture this demographic’s attention, be prepared to entertain and don’t be afraid to polarize the audience. “The days of putting some stupid message up and forcing everyone to see it — that’s so over,” says Alex Bogusky, executive creative director of Crispin Porter + Bogusky in Miami. Crispin Porter is the agency behind Burger King’s ballyhooed “Subservient Chicken” campaign, which showed a man in a chicken suit performing embarrassing tasks at the behest of Abercrombie & Fitch types; a companion Web site lets you type in your own commands and watch the chicken respond. “With this generation,” says Bogusky, “it’s, I know you’re marketing something to me, and you know I know, so if you want me to try a new chicken sandwich, that’s cool — just give me some crazy chicken to boss around.”

Strictly speaking, of course, this isn’t a generation at all. The 18-to-34 demo actually straddles the tail end of Generation X and the leading edge of what demographers are calling the Millennials. “The younger group is a lot more positive,” says Bogusky. “They’re not so angst-ridden, not quite as ironic and cynical. They wanna have fun.” There’s also more of them — some 70 million, compared with 76 million baby boomers and the 41 million in Gen X. Millennials tend to be less suspicious than their predecessors, but they’re still too smart for most marketers. “The hardest job is surprising them,” Bogusky adds. “Usually they know what you’re going to do before you do it.”

“I would recommend that CBS get started right now on how videogames are warping the minds of young people,” says a VP at Electronic Arts. “Perhaps they should run it right after all the gore on ‘CSI.’”

Both groups share a hunger for “authenticity.” If the ad message doesn’t jibe with the brand’s image, forget it. And say good-bye to the hard sell as well. The Subservient Chicken campaign was trashed in Ad Age for failing to push the product, but that was the point. “There’s a huge lure to obscurity,” explains David Art Wales of the New York consulting firm Ministry of Culture. “That’s one of the keys — giving people something to discover, which is the antithesis of the way most advertising works.”

When it comes to media, men 18 to 34 like things fresh, unpredictable, and uncensored. They’re more than twice as likely as other adults to have TiVo or some other DVR. Reality TV is a guilty pleasure, but sitcoms, formulaic and tired, aren’t even tempting. When they do watch TV, guys usually prefer cable channels — Comedy Central, ESPN, HBO, MTV. On the Web, they tend to cluster at porn, gaming, and sports sites. And just because they’re online doesn’t mean they aren’t watching TV and listening to their iPods, too. One of the guys in the focus group even had a mirror on top of his computer screen so he could watch TV without turning around.

“This younger generation has a filter mechanism,” observes Jim Lentz, group VP of marketing at Toyota Motor Sales USA. Lentz has his own focus group at home: two sons, ages 17 and 21. “They can be doing their homework, listening to music, watching TV, on the PC, and on the phone, all at the same time. It drives my wife crazy. You assume they’re just screwing around — but they’re not.” This ability to focus is governed by a complex neural network called the reticular activating system, which filters sensory input to keep the brain from being overwhelmed. When you grow up in an always-on world, this system may adjust to cope. “They have a total ability to block out anything they don’t want to get through,” Lentz marvels. “From an advertising standpoint, that’s what makes this animal so scary.”

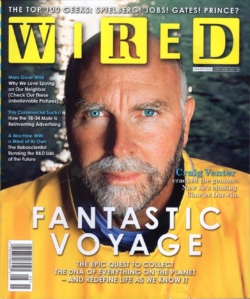

OF COURSE, SOME MEDIA ARE MORE IMMERSIVE than others. As young males drift away from the tube, advertisers are trying to focus on entertainment that grabs their attention and holds it. Tops on that list is videogames. A decade ago, games were considered so geeky that Electronic Arts had to pay real-world companies to reproduce their logos in its sports titles. Now, with Nielsen reporting that young men are spending more time than ever with their TV sets tuned to the game console, big brands like Honda and McDonald’s are paying EA to get in on the action.

“We’re eating the networks’ lunch!” crows Jeff Brown, EA’s vice president of corporate communications, mentally computing the bite EA might someday take out of the television ad market. “Now, this doesn’t happen for 6, 12, 18 months — but when television executives take full measure of how their advertising dollars are moving to videogames, you should prepare yourself for a lot of news stories about how bad videogames are for kids. In fact, I would recommend that Morley Safer get started right now on how videogames are warping the minds of young people. Perhaps” — he grins wickedly at the thought — “they should run it right after all the gore on CSI.”

Even as advertisers experiment with virtual entertainment, they’re trying the opposite tack: delivering messages in the real world, with no electronic intermediary at all. At showings of The Matrix Revolutions last fall, Nissan stuck actors in movie theaters and, when an Altima spot came on, had them stand up and deliver lines from it, like car junkies at a poetry slam. To promote a new line of phonecams, Sony Ericsson hired actors to pose as tourists and ask people to photograph them with the phones. The catch-all term for such campaigns is “experiential,” because the point is to create an experience memorable enough to break through the filter mechanism and generate buzz — something far more likely to register with media-saturated guys than advertising.

Five Companies Change Channels |

|

August 1, 2004

August 1, 2004