Founded in 2015 by Cornelius Tittel, Blau International is based in Berlin and published in English twice annually by Axel Springer. This article was published to coincide with WangShui’s contribution to Stranieri Ovunque–Foreigners Everywhere, the international exhibition of the 60th Venice Biennale, on view from April 20 until November 24, 2024. As noted on the biennale’s website, the title of the exhibition has a dual meaning: first, that wherever you go you will encounter foreigners; and second, that no matter where you find yourself, you will yourself be a foreigner.

Photo: Matt Grubb

“PEOPLE ARE ALWAYS ASKING me, like, where’s the AI? They’re always looking for the AI,” WangShui said. The question should not be entirely unexpected, since the artist has gained a fair amount of attention in recent years for using artificial intelligence in the making of artworks—in an installation at the 2022 Whitney Biennial, for example, that involved two paintings and an LED sculpture from a series which portrayed “this place that only existed between my perception and the machine’s perception.” The paintings in particular seemed—and were—handmade. Yet WangShui looked at me nonplussed, as if to say, isn’t it obvious where the artificial intelligence is? “It’s already in us. It’s like we’re already integrated. I mean, data is already so much a part of our daily lives. We have this constant data input that we’re absorbing. It’s about developing a kind of awareness to how it feels inside our body more than it’s about, you know, creating some sort of binary opposition between humans and machines.”

WangShui and I were having this conversation in a place that looks as far removed from data input as it’s possible to get these days, at least in the northeastern US. We were deep in the countryside, a hundred miles from New York City, in a converted barn that’s surrounded by a cow pasture. The barn is red, as barns in America are supposed to be, but it is sprawling and ungainly, like an overgrown shed. The nearest urban center, if you can call it that, is a hamlet half a mile down the road that boasts a few frame houses and a tiny Protestant church. Just beyond the cow pasture are woods in every direction; except for a couple of tumbledown structures flanking the barn, there’s not a house in sight. It’s an unlikely place to be working with AI, WangShui admitted. But it does offer the kind of soaring interior space that their Manhattan apartment does not.

WangShui and I were having this conversation in a place that looks as far removed from data input as it’s possible to get these days, at least in the northeastern US. We were deep in the countryside, a hundred miles from New York City, in a converted barn that’s surrounded by a cow pasture. The barn is red, as barns in America are supposed to be, but it is sprawling and ungainly, like an overgrown shed. The nearest urban center, if you can call it that, is a hamlet half a mile down the road that boasts a few frame houses and a tiny Protestant church. Just beyond the cow pasture are woods in every direction; except for a couple of tumbledown structures flanking the barn, there’s not a house in sight. It’s an unlikely place to be working with AI, WangShui admitted. But it does offer the kind of soaring interior space that their Manhattan apartment does not.

“AI is a tool to simulate and mirror dimensions of consciousness. It should be a tool to help evolve our species. I think it could save our species.”

WangShui doesn’t think much of binary opposition, whether it’s humans versus machines, or humans versus other humans. They identify as non-binary, and many aspects of their being seem an expression of that: the extreme variety of their work, which can range from a cascade of LEDs to an oil painting on aluminum to a habitat for silkworms; their resistance to being attached to some sort of narrative; even their past reluctance to be photographed. “The contemporary conception of identity is that you are this. You have a fixed identity,” they said. “And in the art world it’s really become a thing—you’re an artist that fits in this category, which means you produce this type of work. It really is this kind of trap. If we all kind of orient ourselves to expand our perceptive structures, we won’t be trapping each other. We’ll actually be seeing each other more fully.”

Does this attitude have something to do with their being queer, being trans?

“Yeah. I mean, it’s that same kind of oscillation. To me, being trans, it’s not about any point of arrival. It’s about this constant practice of being aware and shifting, and being comfortable with that fluidity. It’s not about getting somewhere.”

“Cathexis I, II and III,” 2024, hand-etched aluminum. Installation view, 60th Venice Biennale. Photo: Nick Ash

THOUGH WANGSHUI OFTEN appears quite glamorous in photo shoots, this was a workday, a Tuesday afternoon in February with a rapidly approaching deadline for the Venice Biennale, where their installation is being featured in the international exhibition. They were dressed for work: black running pants and a dark gray zip-up Protémoa sweater, with their long black hair tied back and up and out of the way.

Art Starsand the machinery behind them. |

WangShuiObsessed with the origins of consciousness and humanity’s preoccupation with violence, WangShui hopes that, through AI, love will find a way.

|

A ‘Holopoem’ for the CosmosEduardo Kac found an unusual public space for his artwork — orbiting the sun.

|

Making Art Out of Bombshells and Memories in VietnamTuan Andrew Nguyen’s videos and sculptures uncover haunting artifacts and stories from the Vietnam War.

|

David Byrne Is Totally ConnectedThere’s a new gallery show of his whimsical drawings — and coming this summer, an immersive art-and-science experience.

|

A.I. Meets Fatherhood in an Artist’s New WorkIan Cheng’s latest: a narrative animation powered by a game engine and partly inspired by his two-year-old.

|

Frank Gehry’s Disney Hall Is TechnodreamingData artist Refik Anadol creates a swirling projection on steel for the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

|

Alan Vega Ignored the Art World. It Won’t Return the Favor.A year after his death, the lead singer of Suicide looms over the downtown art scene.

|

The Whitney After AllThe Whitney Museum never really fit in uptown. Now it has relocated to a part of the Village that until recently was a reeking abattoir. Home, sweet home.

|

A Palace of WondersThe Panza Collection mounts a show challenging perceptions.

|

Last LaughJay Gorney sells art that sends up collectors. “They hear tom-toms in the distance,” says a curator, “and they get out their checkbooks.”

|

Cool John B.John Baldessari got rid of all the extraneous stuff, like form and beauty. Now he’s the éminence grise of conceptualism, in the spotlight at last.

|

As the Art World TurnsThe mix of art, big bucks and hype has turned the art world into a soap opera. Which brings us to Julian Schnabel . . .

|

The floor of the barn was unpolished concrete. In front of an oversized garage door sat a plywood worktable scattered with stuff—magazines, water bottles, a MacBook, a printer, Philip Ball’s lavishly illustrated Patterns in Nature, Franco Berardi’s semiotext(e) book Breathing: Chaos and Poetry. Above the table, the garage door’s lone row of glass panes was buzzing with flies—a feature WangShui has learned to live with. On the wall across from the table, the artist had taped little digital printouts of paintings they’d made for their solo exhibition Window of Tolerance at the Haus der Kunst in Munich. But the studio was dominated by three four-meter-high aluminum panels, each of them incised with a swirling, cryptic design. Arched at the top, these panels looked like vastly overscaled altarpieces bearing the marks of some primitive, possibly gnostic gospel. Their titles are Cathexis I, II, and III.

The panels were bound for the Arsenale, Venice’s 900-year-old naval shipyard, where they would be fitted into a trio of enormous, arched windows in the 16th-century Artiglierie. The three pieces would get almost imperceptible traces of pigment before being shipped off a week from now. “I’ve been in this process in the past three years of just really creating different types of marks,” they said, walking up to the panel with the most elaborate design. “This is probably the most complicated one I’ve made. Like this, for example, is done with a certain grade of sandpaper.” They pointed to an abraded part of the surface, then to a nearby section incised with small, overlapping circles. “This is done with a metal brush. This is kind of like a circular motion. And these rings”—they pointed to a series of widely separated oval shapes—“I use, like, these dental tools. It actually can sound like nails on a chalkboard, right? But somehow it felt so good.”

Stepping back, I registered in this intricate design a long, coiled presence—more than one, actually.

“I don’t know, I think this snake just appeared and kind of took over the painting,” said WangShui. “And since then I’ve been trying to kind of trace where that comes from in terms of consciousness.” This has led them down some rather esoteric paths. They mention The Cosmic Serpent, a 1998 book by Jeremy Narby, a Canadian anthropologist who went to Peru, got down with the native culture, and ended up—“it’s kind of like shamans and ayahuasca ceremonies, it’s that kind of book,” said WangShui. One of its main lessons is that “nature has its own language, and that language is form. So he needed to stop over-thinking everything and just follow the form.” Eventually, after various hallucinations and a significant amount of form-following, Narby began to register the resemblance of twin snakes—a universal symbol of knowledge, death, rebirth—to the twisting strands of DNA. “So I’ve become really fascinated with it as a kind of symbol that’s related to what they call the origin of knowledge,” WangShui went on. “It just came to me that these works should be about snakes somehow.”

Not that you have to go to the Peruvian Amazon and drink ayahuasca to find snake symbolism that’s tied to the origin of knowledge. WangShui is Chinese-American, born in Dallas in 1986 to Christian parents. Fervently religious and deeply conservative, they moved to Thailand when WangShui was little and served as missionaries there. They were hardly supportive of WangShui’s emerging identity as a trans person. Masculine/feminine, Asian/American—“I was always in this very liminal kind of space,” they said, a space of perpetual transition. “I was having to, you know, deal with and resist my parents, their ideologies. And there was this whole other world in front of me—that was where I was heading, but I almost didn’t have enough agency to have it.”

Eventually, though, they turned 18. Back in California, they enrolled in Pasadena City College, then transferred to the University of California, Berkeley, to study art and social anthropology. This led to another problem, however. “When I got to Berkeley, I got all these grants and fellowships and things where I was always having to narrativize my biography. And everyone wanted a very simple story that was, you know, logical or digestible. They want to place you or label you. And so much of my work is about evading those structures.”

“Cathexis II,” 2024, hand-etched aluminum. Installation view, 60th Venice Biennale. Photo: Nick Ash

EVADING INDEED. What WangShui calls liminal, others might consider fugitive. No great surprise, then, that they should appear in Going Dark, a recent group exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York that featured mostly Black artists— Glenn Ligon, Kerry James Marshall, Faith Ringgold, Carrie Mae Weems, and Charles White among them—and the “strategies of concealment” they have pursued. WangShui’s strategy has to do with what they call “these in-between spaces,” “this negative space.” That’s where they feel comfortable, where they wish to dwell, in a realm where neither they nor their work can be pinned down. “That’s why I always want to keep it moving between these many different formats,” they said. “Every project that I did I presented in a different medium, because I wanted people to know that they weren’t going to get one thing. It was about building a freedom into it for myself.”

“That’s the time that I feel like we’re living in. There are these dual narratives about progress and inclusion, but there’s also this intense dimension of violence.”

Before snakes, it was reality TV. WangShui spent the couple of years after the pandemic hit in thrall to The Bachelor, the ABC reality show that pits a dozen or so seductive women against each other in an increasingly desperate bid to win the affections of a studly man, or at least persuade him not to dump them next. The show trucks in shock and randiness and hope and heartbreak, and what it doesn’t provide—any actual sense of reality, for example—was for several seasons more than made up for by UnREAL, a fictional counterpart co-created by a former producer on The Bachelor. “It’s about these two powerful women who are kind of like really manipulative and just create all of this drama,” WangShui said of UnREAL. “It’s kind of about this way that we’re exploiting people’s identities. That’s the time that I feel like we’re living in. There’s these dual narratives about, like, progress and inclusion, but there’s also this intense dimension of violence.”

WangShui’s response was on display in the exhibition at the Haus der Kunst. In the first room, a series of oil-on-aluminum paintings created in partnership with an AI—each one a comment on some aspect of reality TV. Pillow IV (Amazing Taste) (2023) alluded to the air of sensuousness and luxury that reality shows project, while the clutch of champagne glasses in the painting Window of Tolerance (2023) suggested not just extravagance but inebriation and lowered inhibitions. Over in the second room, playing out on a large screen, was Certainty of the Flesh (2023), an AI-driven simulation of the “reality” dynamic at work, a breathless sequence of OMG! moments masking the true reality of exploitation and sleaze.

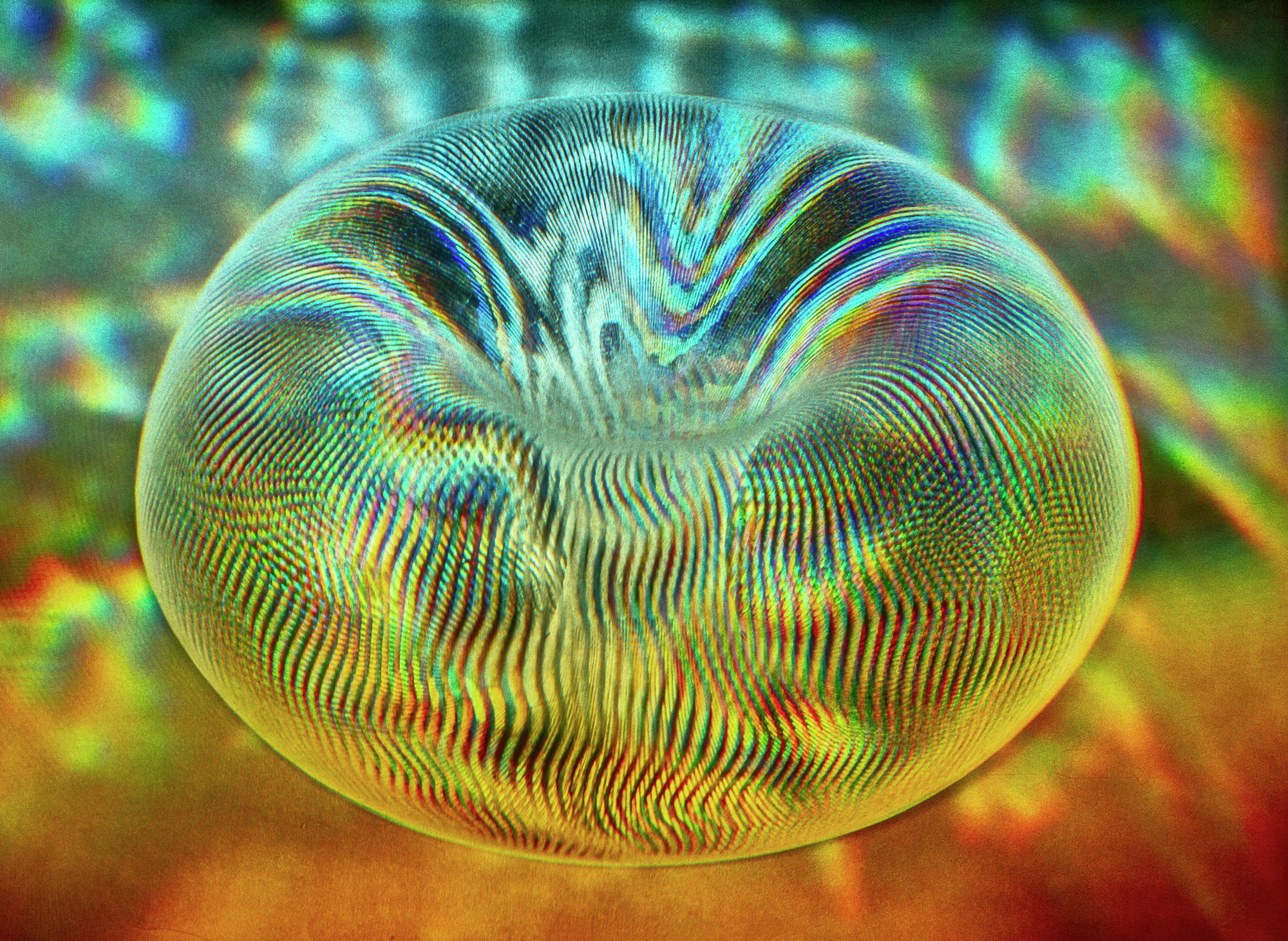

“Lipid Muse,” 2024, multichannel simulation with woven LED screens, sensors and sound. Installation view, 60th Venice Biennale. Photo: Nick Ash

April 22, 2024

April 22, 2024