The new home of the Whitney Museum of American Art at dusk, viewed from the east. In the foreground is the southern terminus of the High Line, the public park built on an elevated freight railway in a formerly industrial zone on Manhattan’s West Side. Photo: Ed Lenderman

Cover: “Hudson Street,” by George Ault, 1932. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

SOME THINGS JUST AREN’T MEANT to fit in. The Whitney Museum of American Art certainly sounds like an august institution. But it was born on a scruffy back street in Greenwich Village at a time when “bohemian” meant “disreputable,” and during its six decades uptown—most of them at Madison Avenue and Seventy-Fifth Street, in the moneyed precincts of the Upper East Side—it never really outgrew its origins. It did, however, outgrow its starkly modernist home, Marcel Breuer’s inverted ziggurat from 1966. In addition to the usual curatorial squabbles and courting of benefactors and some epic board disputes, the Whitney spent decades trying to assuage its neighbors while somehow finding a way to expand. The task was hopeless. So it was with a feeling not just of relief but of joy that last spring, having renounced its uptown location, the museum opened the doors to an expansive new building in the part of downtown Manhattan that until a few years ago was a reeking abattoir. Home, sweet home.

“Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney” by Robert Henri (1865–1929), 1916. Oil on canvas, 50 by 72 inches. Gift of Flora Whitney Miller.

The Whitney has never been just a museum. It was founded as an outgrowth of a campaign to champion and support American art. Today this cause is as dominant as the Whitney’s new location in the Meatpacking District is chic. But when Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, the museum’s founder, embarked on her crusade a little more than a century ago, American art and Greenwich Village seemed equally dodgy. What’s most surprising about the new Whitney may be its ability to remind us that in some ways, they still are.

Art Starsand the machinery behind them. |

WangShuiObsessed with the origins of consciousness and humanity’s preoccupation with violence, WangShui hopes that, through AI, love will find a way.

|

A ‘Holopoem’ for the CosmosEduardo Kac found an unusual public space for his artwork — orbiting the sun.

|

Making Art Out of Bombshells and Memories in VietnamTuan Andrew Nguyen’s videos and sculptures uncover haunting artifacts and stories from the Vietnam War.

|

David Byrne Is Totally ConnectedThere’s a new gallery show of his whimsical drawings — and coming this summer, an immersive art-and-science experience.

|

A.I. Meets Fatherhood in an Artist’s New WorkIan Cheng’s latest: a narrative animation powered by a game engine and partly inspired by his two-year-old.

|

Frank Gehry’s Disney Hall Is TechnodreamingData artist Refik Anadol creates a swirling projection on steel for the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

|

Alan Vega Ignored the Art World. It Won’t Return the Favor.A year after his death, the lead singer of Suicide looms over the downtown art scene.

|

The Whitney After AllThe Whitney Museum never really fit in uptown. Now it has relocated to a part of the Village that until recently was a reeking abattoir. Home, sweet home.

|

A Palace of WondersThe Panza Collection mounts a show challenging perceptions.

|

Last LaughJay Gorney sells art that sends up collectors. “They hear tom-toms in the distance,” says a curator, “and they get out their checkbooks.”

|

Cool John B.John Baldessari got rid of all the extraneous stuff, like form and beauty. Now he’s the éminence grise of conceptualism, in the spotlight at last.

|

As the Art World TurnsThe mix of art, big bucks and hype has turned the art world into a frothy soap opera. Which brings us to Julian Schnabel . . .

|

Born in 1875 to the richest family in America and married in 1896 into yet another great fortune, Mrs. Whitney was surrounded by almost unfathomable wealth. Her great-grandfather, who died just before she turned two, was the man who inspired the term “robber baron.” She resided in an opulent Fifth Avenue mansion when she wasn’t at the estate on Long Island or the “cottage” in Newport or her husband’s hunting plantation in South Carolina. But after a trip to Paris in 1901 unleashed a passion for art, she contracted some rather queer notions. Rejecting the life of a corseted and cosseted bauble, she studied sculpture and became an artist herself. She opened a studio in a converted stable in MacDougal Alley, which at the time was hardly the flower-bedecked cul-de-sac it is today. In 1916, when her friend Robert Henri painted a glamorous portrait that showed her lounging odalisque-like in silk pajamas, her husband refused to hang it because it showed her, as he put it, “in pants.” So much for the “palace of art,” as their Stanford White mansion at Sixty-Eighth and Fifth had come to be known. By then Gertrude was spending much of her time downtown anyway, making art, consorting with other artists, and along the way assembling a collection that ran directly counter to the prevailing taste for European masters, old or otherwise.

This collection is the Whitney Museum’s entire reason for being. In 1929 Mrs. Whitney, having bought American paintings and sculptures for years and displayed them from time to time in a row of town houses she bought on West Eighth Street abutting her studio, sent her associate Juliana Force to offer them to the Metropolitan, along with the money to build a new wing. “What will we do with them, dear lady?” the Met’s director famously responded. “We have a cellar full of those things already.” Two years later, the newly chartered Whitney Museum opened its doors in the reconfigured Eighth Street town houses.

“A museum’s collection is like its DNA,” I was told by Adam D. Weinberg, the Whitney’s director since 2003. “It’s the springboard from which your mission begins.” Mrs. Whitney’s collection—adventuresome, controversial, deliberately unsafe—set the Whitney on its quest. And yet the Breuer building was so cramped that even as the collection grew, it spent most of its time locked away in storage. “There were times when we only had thirty or forty works on view,” Weinberg says. Now, with nearly double the exhibition space the museum had uptown, “we can have a couple hundred.” The opening show, a vast survey drawn entirely from the collection and titled (after a line in a Robert Frost poem) America Is Hard To See, signaled the Whitney’s new priorities. Now that it has come down, Weinberg and his chief curator, Donna De Salvo, plan to devote the entire sixth and seventh floors to works the museum owns.

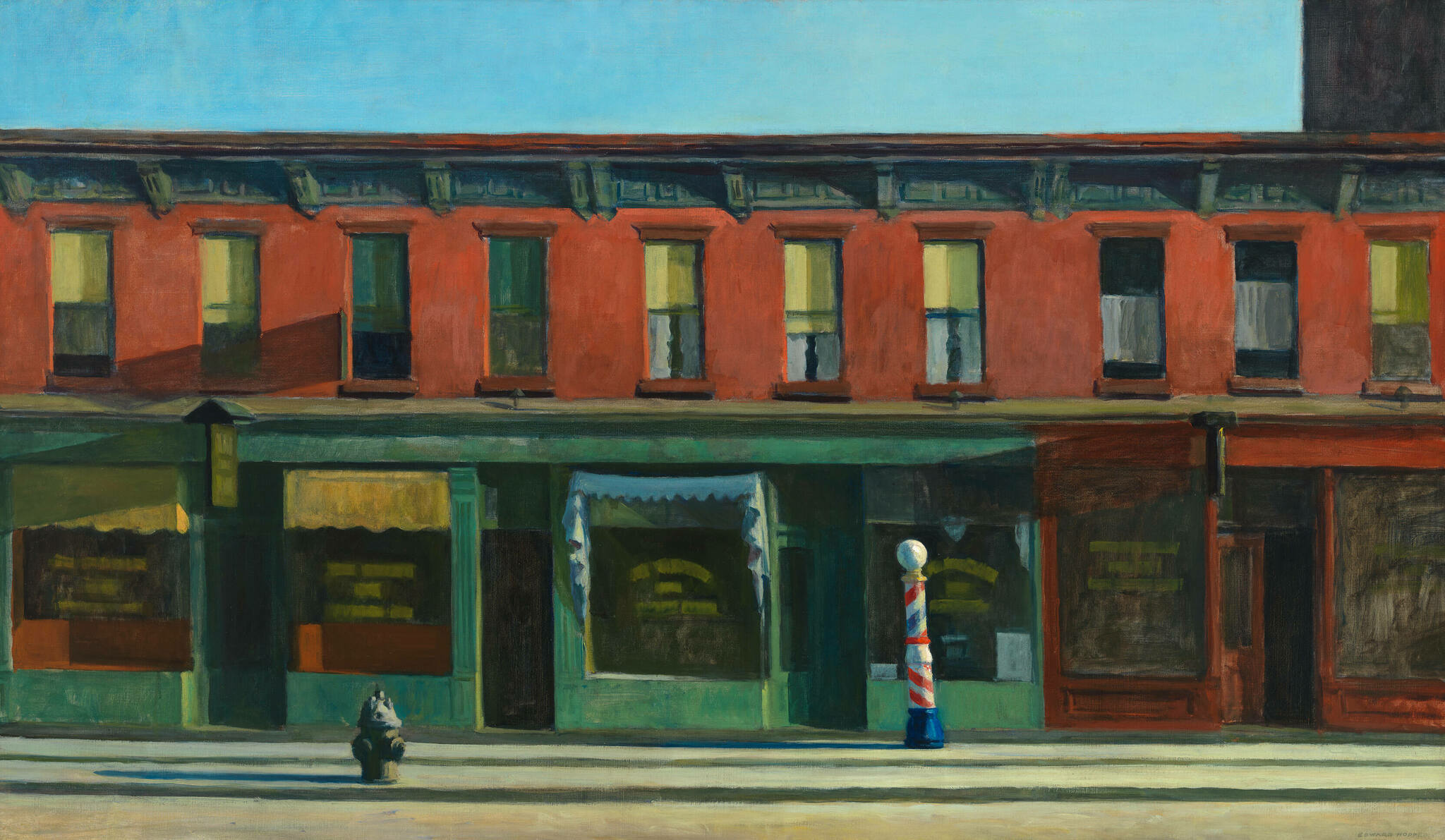

What’s remarkable about the Whitney’s collection is not just how many iconic works of art it contains—George Bellows’s Jazz Age knockout Dempsey and Firpo, Edward Hopper’s Seventh Avenue storefront reverie Early Sunday Morning, Jasper Johns’s pop emblem Three Flags, to name a few—but how many were bought almost before the paint was dry. “Mrs. Whitney was buying works right at the time the art was being made,” Weinberg says. She purchased Early Sunday Morning in 1931, months after Hopper painted it. She acquired Georgia O’Keeffe’s The White Calico Flower in 1932, the year after O’Keeffe made it. “Some of the work was great, some a little less interesting,” Weinberg admits, “but she was there. She was taking risks, not waiting for somebody else to stand up.”

“Dempsey and Firpo” by George Bellows (1882–1925), 1924. Oil on canvas, 51 ⅛ × 63 ¼ inches. Purchase, with funds from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney.

It’s largely because of her support that Hopper is considered a major artist today. But the risk-taking hardly stopped there. Particularly significant was the backing she gave African Americans and women. Among her most striking acquisitions is Congolais, a carved head by Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, who lived in Paris and was a key figure in the New Negro Movement, as the Harlem Renaissance was known in its day. Elsie Driggs’s Pittsburgh, a stark, precisionist view of a nightmarish-looking steel mill, was another early acquisition. Mrs. Whitney extended her support to artists as diverse as Isabel Bishop, whose etchings and drawings documented the street life around Union Square, and Charles Sheeler, whose brooding River Rouge Plant captured the power of America’s burgeoning industrial might. Male or female, black or white, all benefitted from her patronage.

“Early Sunday Morning” by Edward Hopper (1882–1967), 1930. Oil on canvas, 35¼ by 60 ¼ inches. Purchase, with funds from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney.

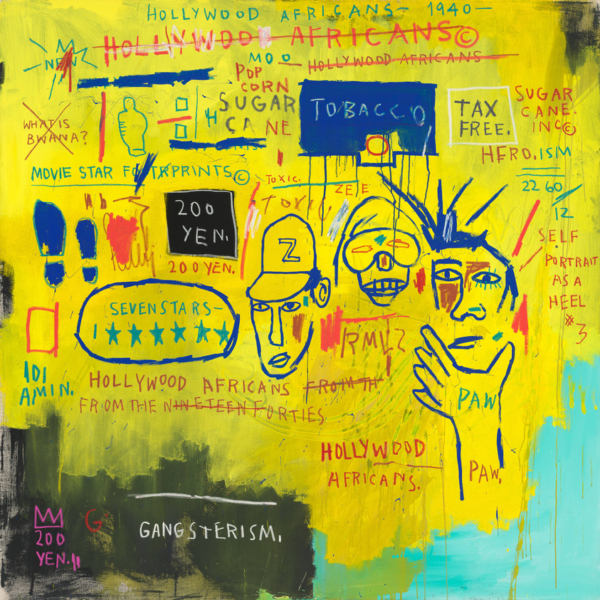

AFTER HER DEATH IN 1942, that support became considerably more erratic. Ironically, the post-Whitney Whitney seemed to lose its way just as American art was on the verge of triumph. Its ongoing commitment to the realism of Mrs. Whitney’s day made it slow to embrace abstract expressionism and pop. On occasion, it was still adventurous enough to acquire major artworks shortly after they were made: Franz Kline’s abstract expressionist gem Mahoning from 1956, Wayne Thiebaud’s Pie Counter from 1963, not to mention Jean-Michel Basquiat’s disturbingly primitive Hollywood Africans from 1983 or Mike Kelley’s 1987 stuffed-dolls-and-afghans assemblage More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid—a mordant send-up of sentimentality that today seems iconic. But a telling incident was the 1977 firing of Marcia Tucker, a curator who championed women painters like Lee Krasner and Joan Mitchell, for organizing a Richard Tuttle show that conservative critics saw as rubbishy doodads masquerading as art. (A few inches of old cord? “Pathetic,” thundered Hilton Kramer, the Antonin Scalia of art critics, in the New York Times.) Tucker went on to start the New Museum in lower Manhattan. And then there was Thomas N. Armstrong, the director who fired her—and whose own dismissal in 1990 triggered such bad feelings that Mrs. Whitney’s granddaughter, Flora Miller Biddle, eventually resigned from the board.

“My Egypt” by Charles Demuth (1883-1935), 1927. Oil, fabricated chalk, and graphite on composition board; 36 x 30 inches. Purchase, with funds from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney.

Despite his handling of the Tuttle contretemps, Armstrong was largely responsible for transforming the Whitney from the somewhat amateurish establishment it had become after Mrs. Whitney’s death into a modern museum—the kind of place that could fill in the holes in its collection with such dramatic gestures as the 1980 purchase of Johns’s Three Flags for $1 million, a sum that was unheard-of at the time. By 1989 the permanent collection had grown from two thousand works when he arrived to eighty-five hundred. But where to put them? Instead of being defined by the collection, the Whitney’s identity became bound up with the misdirection and confusion that characterized its long struggle to expand beyond its Breuer box—a struggle that would claim first Armstrong and later a second director.

The main problem was its neighborhood. Women in pants were no longer verboten, but bold architectural statements were not allowed. The Breuer building had hardly been a welcome addition when it went up—Ada Louise Huxtable, writing in the Times, resorted to understatement when she called it “the most disliked building in New York”—but that was before historic preservation and neighborhood activism congealed into the neophobic juggernaut they are capable of forming today. By 1985, when Armstrong announced a ten-story addition by the postmodern architect Michael Graves that would require the demolition of a row of neighboring nineteenth-century brownstones, the Whitney was sitting in the midst of a city-designated historic district. Graves’s plan was greeted with towering outrage: modernists hated it for diminishing the Breuer building, while traditionalists hated it for daring to exist at all. Both camps might have been forgiven for concluding that Graves was perhaps better suited to designing tea kettles. He produced first one redesign and then another, to no avail. In 1989 the plan was finally scrapped. Armstrong quickly followed.

“Three Flags” by Jasper Johns (1930-), 1958. Encaustic on Canvas, 30 ⅝ by 45 ½ by 4 ⅝ inches. Purchase, in honor of the museum’s 50th anniversary.

During the tenure of his successor, David A. Ross, the Whitney experienced what would later be recognized as a defining moment: the 1993 Biennial. The museum had been holding biennial surveys of contemporary American art since 1973 (before that they were staged annually), and inevitably these shows would be condemned as trendy or, if that was evidently not the case, incoherent. But the 1993 Biennial surpassed all expectations in this regard. Big paintings by men in big suits—the staple of art in the 1980s, a heady throwback to the postwar glory years of abstract expressionism—had seemingly gone missing. In their place, visitors encountered caustic installations, puzzling videos, and challenging conceptual works, many by women and most bearing some sort of political freight. AIDS and race were big. Luscious brushstrokes were out.

The response from critics was a sustained, collective howl. Robert Hughes dismissed the entire undertaking as “preachy and political.” Los Angeles Times critic Christopher Knight used the words “almost excruciating.” “I hate the show,” Michael Kimmelman declared flatly in the New York Times. Roberta Smith, also writing in the Times, described it as “a pious, often arid show”—but she also called it “a watershed,” which turned out to be prescient. For the 1993 Biennial marked a turning point: out with cigar-puffing and bombast (Julian Schnabel had been a star of the previous biennial, and of two others before); in with personal expressions of pain, loss, remembrance, and sometimes wonder. Twenty years later, Jerry Saltz would recall it in New York magazine as “the moment in which today’s art world was born.”

The response from critics was a sustained, collective howl. Robert Hughes dismissed the entire undertaking as “preachy and political.” Los Angeles Times critic Christopher Knight used the words “almost excruciating.” “I hate the show,” Michael Kimmelman declared flatly in the New York Times. Roberta Smith, also writing in the Times, described it as “a pious, often arid show”—but she also called it “a watershed,” which turned out to be prescient. For the 1993 Biennial marked a turning point: out with cigar-puffing and bombast (Julian Schnabel had been a star of the previous biennial, and of two others before); in with personal expressions of pain, loss, remembrance, and sometimes wonder. Twenty years later, Jerry Saltz would recall it in New York magazine as “the moment in which today’s art world was born.”

“Hollywood Africans” by Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–1988), 1983. Acrylic and oil stick on canvas, 84 inches square. Gift of Douglas S. Croner.

November 1, 2015

November 1, 2015