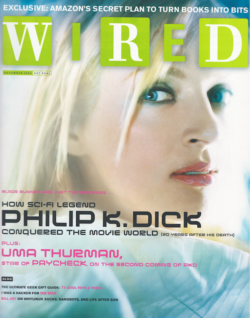

Twenty years after the release of Blade Runner, Philip K. Dick was the hottest scribe in Hollywood. How did that happen? Wired went to the set of Paycheck in Vancouver and sat down with his daughters in Palo Alto to find out.

Photo: Nicole Panter

THE UNBILLED COSTAR of Paycheck, the latest Hollywood thriller from the battered typewriter of Philip K. Dick, is a bullet. A crack engineer named Jennings, played by Ben Affleck, finds himself in a jam, as Dick’s characters invariably do, and the bullet is headed his way. Spiraling through the air in super-slow motion, it pierces his chest in a plume of red and bores into his heart. Or does it? Though the image recurs throughout the film, it’s hard to tell whether it’s actually happening or not. Philip K. Dick liked nothing better than to toy with the fundamentals of human existence, reality chief among them, so what better for the movie than a bullet that may or may not be tearing through the main character’s flesh? Like other Dick protagonists—Tom Cruise in Minority Report, Arnold Schwarzenegger in Total Recall, Harrison Ford in Blade Runner—Affleck finds himself struggling for equilibrium in a world where even the most elemental questions are almost impossible to answer. Can the senses be trusted? Are memories real? Is anything real?

Paycheck, directed by John Woo and set to open Christmas Day, is the latest in a run of films based on Philip K. Dick stories that began 21 years ago with Blade Runner. The writer’s hallucinatory tales make for suspense with an epistemological twist: full-bore action pics that turn on questions of perception versus reality. Having agreed to have his memory erased after completing a super-sensitive job, Jennings learns that he apparently signed away his $4.4 billion paycheck in exchange for an envelope of trinkets. Armed men are chasing him, but he has no idea why until he teams up with Rachel (Uma Thurman), whom he vaguely recalls meeting just before he started the job. Jennings, it turns out, is a man who has seen the future but can’t remember it.

Dick died shortly before Blade Runner’s release in 1982, and, despite a cult readership, he spent most of his life in poverty. Yet now, more than two decades later, the future he saw has made him one of the most sought-after writers in Hollywood. Paycheck, based on a 1953 short story Dick sold to a pulp magazine for less than $200, will bring close to $2 million to his estate. And movies based on more than a half-dozen other stories and novels are in the works—among them “The King of the Elves” at Disney, “The Short, Happy Life of the Brown Oxford” at Miramax, and A Scanner Darkly at Warner Bros.

Like the babbling psychics who predict future crimes in Spielberg’s “Minority Report,” Dick was a precog.

Dick’s anxious surrealism all but defines contemporary Hollywood science fiction and spills over into other kinds of movies as well. His influence is pervasive in The Matrix and its sequels, which present the world we know as nothing more than an information grid; Dick articulated the concept in a 1977 speech in which he posited the existence of multiple realities overlapping the “matrix world” that most of us experience. Vanilla Sky, with its dizzying shifts between fantasy and fact, likewise ventures into a Dickian warp zone, as does Dark City, The Thirteenth Floor, and David Cronenberg’s eXistenZ. Memento reprises Dick’s memory obsession by focusing on a man whose attempts to avenge his wife’s murder are complicated by his inability to remember anything. In The Truman Show, Jim Carrey discovers the life he’s living is an illusion, an idea Dick developed in his 1959 novel Time Out of Joint. Next year, Carrey and Kate Winslet will play a couple who have their memories of each other erased in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. Memory, paranoia, alternate realities: Dick’s themes are everywhere.

Welcome to Hollywood |

How does the movie business work? Or (spoiler alert) does it work at all? |

The Blockbuster SyndromeWill Hollywood’s road to success be paved with ever-fewer, ever-more-expensive mega-movies?

|

Movies of the FutureGoodbye, passive viewing. Soon, every moviegoer will be a player.The New York Times | June 23, 2013 |

‘Avatar’: The CreationBuilding the world of “Avatar” meant inventing effects you’ve never seen before.Wired 17.12 | December 2009 |

A Second Chance for 3-DTrilogies are done. CGI is ho-hum. Now Hollywood directors are tapping into the third dimension — starting with Angelina Jolie in ‘Beowulf.’

|

Close Encounters of the Worst KindThis time, E.T. wants to kill us. How Steven Spielberg reinvented ‘War of the Worlds’ in 72 days and learned to love digital filmmaking—fast.

|

The Second Coming of Philip K. DickThe inside-out story of how a hyper-paranoid, pulp-fiction hack conquered the movie world 20 years after his death.

|

No Flowers, Send MoneyProducer Barry Navidi had it all—$13 million to play with and Marlon Brando, Debra Winger, Johnny Depp and John Hurt signed. Yet the picture folded two weeks into the shoot. What went wrong?Los Angeles Times | December 17, 1995 |

At a time when most 20th-century science fiction writers seem hopelessly dated, Dick gives us a vision of the future that captures the feel of our time. He didn’t really care about robots or space travel, though they sometimes turn up in his stories. He wrote about ordinary Joes caught in a web of corporate domination and ubiquitous electronic media, of memory implants and mood dispensers and counterfeit worlds. This strikes a nerve. “People cannot put their finger anymore on what is real and what is not real,” observes Paul Verhoeven, the one-time Dutch mathematician who directed Total Recall. “What we find in Dick is an absence of truth and an ambiguous interpretation of reality. Dreams that turn out to be reality, reality that turns out to be a dream. This can only sell when people recognize it, and they can only recognize it when they see it in their own lives.”

Like the babbling psychics who predict future crimes in Minority Report, Dick was a precog. Lurking within his amphetamine-fueled fictions are truths that have only to be found and decoded. In a 1978 essay called “How to Build a Universe That Doesn’t Fall Apart Two Days Later” he wrote: “We live in a society in which spurious realities are manufactured by the media, by governments, by big corporations, by religious groups, political groups. I ask, in my writing, What is real? Because unceasingly we are bombarded with pseudorealities manufactured by very sophisticated people using very sophisticated electronic mechanisms. I do not distrust their motives. I distrust their power. It is an astonishing power: that of creating whole universes, universes of the mind. I ought to know. I do the same thing.”

DICK’S CAREER IN MOVIES did not begin with a bang. It was 1977, and a small-time actor named Brian Kelly wanted to option the 9-year-old novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? For a mere $2,500, he got it. “The works of Philip K. Dick were not exactly in demand,” recalls the writer’s New York literary agent, Russell Galen, “and for Phil”—then 49 and living in suburban Orange County—“that was enough to make the difference between a good year and a bad year.” Kelly’s partner wrote a screenplay and shopped it around. Eventually it landed on the desk of Ridley Scott, who’d just directed Alien. Scott brought in a new writer and sent it to Alan Ladd Jr., one of the top players in Hollywood.

“I liked the project,” says Ladd, a quiet, deliberate man whose Beverly Hills offices are lined with posters for the films he’s made: Star Wars, The Right Stuff, Chariots of Fire, Braveheart. “It was a good old-fashioned detective story set in the future.” Ladd thought Harrison Ford, who’d costarred in Star Wars, would be good as a Humphrey Bogart-type sleuth. Blade Runner was a go.

Just a few months before the movie’s release, Dick suffered a massive stroke. Blade Runner proved only a modest success at the box office; if not for two other developments, Dick’s career might have died with him. The first was the emergence of home video, which gave new life to small films with cult followings. Throughout the ’80s, Blade Runner‘s reputation as a noirishly futuristic gem continued to build. The second was the interest of Ron Shusett, a screenwriter who’d worked on Alien. Before Dick died, Shusett bought the film rights to “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale,” a story about a nebbishy clerk with dreams of going to Mars. He retitled it Total Recall and took it to Dino De Laurentiis, who put it into development.

Cronenberg wrote a dozen drafts of “Total Recall.” Finally they said, “You know what you’ve done? You’ve done the Philip K. Dick version. We want ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark Go to Mars.’”

Total Recall languished for years before all the elements—producer, director, star—came together. At one point, Richard Dreyfuss was attached. At another, David Cronenberg was going to direct and wanted William Hurt for the lead. “I worked on it for a year and did about 12 drafts,” Cronenberg recalls. “Eventually we got to a point where Ron Shusett said, ‘You know what you’ve done? You’ve done the Philip K. Dick version.’ I said, ‘Isn’t that what we’re supposed to be doing?’ He said, ‘No, no, we want to do ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ Go to Mars.’” Cronenberg moved on. Arnold Schwarzenegger wanted to star, but De Laurentiis refused: Even in an overamped Hollywood bastardization, he couldn’t see Schwarzenegger in the part. Instead, it went to Patrick Swayze, with Bruce Beresford directing. They were building sets in Australia when De Laurentiis’s company went bankrupt.

This gave Schwarzenegger his chance. He got Carolco, the high-flying mini-studio behind the Rambo series, to buy the property, and Paul Verhoeven to direct it. The henpecked clerk named Quail became a muscle-bound construction worker named Quaid, and a new ending was written to make up for what many filmmakers see as the problem with Dick’s short stories: their lack of a third act that will take a movie to 90 minutes or more. But while Verhoeven’s film was an interplanetary shoot-’em-up that bore little resemblance to Dick’s story, it did retain the tale’s essential ambiguity: At the end, we’re not sure whether the main character actually went to Mars or only thought he did, thanks to some memory implants he bought. “This was extremely innovative, coming from a Hollywood studio,” says Verhoeven. “To dare to say, Everything you see could be a dream, or everything you see could be reality, and we won’t tell you which is true—I thought that was pretty sensational.”

Read . . .

Philip K. Dick Goes Legit

How Jonathan Lethem wrestled the most outré science-fiction writer of the 20th century into the canon of American literature.

Wired 15.06 | June 2007

Total Recall was one of the biggest hits of 1990, grossing $118 million in the US alone. That was good for Carolco, even better for Dick. “The whole phenomenon of Philip K. Dick short stories selling for a lot of money started with Total Recall,” says Russell Galen, the literary agent, who now represents his estate. Before Total Recall, Dick was a Hollywood unknown; afterward, screenwriters and producers saw his stories as properties they could build action movies around. And there were dozens of these properties—36 novels and more than 150 short stories, most as-yet unoptioned.

It would be a while before anything was available. Dick had died without a will, and his estate was in probate for 11 years. When it was finally settled, however, Galen had work to do. Warner Bros. bought the novel Time Out of Joint for Joel Silver (who went on to produce the Matrix series) and optioned A Scanner Darkly for George Clooney and Steven Soderbergh’s production company, Section 8. The Jim Henson Company optioned “The King of the Elves” and set it up as a children’s film at Disney. Spyglass Entertainment, makers of M. Night Shyamalan’s The Sixth Sense, took an option on “Paycheck.” Business got so heavy that Galen had to devise a computerized chart showing what’s available, what’s been optioned and will become available in the future, and what’s been sold outright.

Verhoeven envisioned “Total Recall II: The Minority Report” as a whiz-bang, action-packed, “theological-philosophical challenge” to the idea of predestination. But the studio went bankrupt before he could make it.

One of the first to go was “The Minority Report,” a short story published in the January ’56 issue of Fantastic Universe, about a police commander who uses clairvoyants to arrest people before they actually commit a crime. Gary Goldman, the screenwriter who’d reworked Total Recall for Verhoeven, brought it to the director, who decided it would make a great sequel. This was a story in which Dick’s obsession with alternate realities dovetailed with a fascination with fate: If we can see into the future, does that mean the future is set? That humans have no capacity for free will? Verhoeven envisioned Total Recall II: The Minority Report as a whiz-bang, action-packed, “theological-philosophical challenge” to the Calvinist concept of predestination. But Carolco went bankrupt before he could make it. So Goldman took it to director Jan de Bont, Verhoeven’s former cinematographer, who showed it to Tom Cruise, who’d been thinking for some time about doing a science fiction picture with Steven Spielberg.

To Galen, the 1998 announcement that Cruise and Spielberg would team up to make Minority Report was electrifying. Three years passed before they actually got to it, and when they did the movie departed significantly from the short story, which was a paranoia-soaked potboiler in which the police commander in charge of “pre-crime” is framed by his new deputy, or his wife, or an ex-general, or all or none of the above. “I don’t think Phil was all that interested in the morality of pre-crime,” says Goldman, an executive producer of the film. But Spielberg was, and the movie ends with a ringing endorsement of the American justice system. “It’s very difficult to be true to Phil Dick and make a Hollywood movie,” Goldman observes. “His thinking was subversive. He questioned everything Hollywood wanted to affirm.” No matter. With the release of Minority Report, Dick became an A-list Hollywood scribe, a player, a member of the club.

“Paycheck” director John Woo made his name with violent ballets of bullets. His new inspiration: Hitchcock. Photo: Art Streiber

VANCOUVER, JUNE 2003. The Paycheck shoot is well under way, and this morning Woo is rehearsing one of the opening scenes. A vast soundstage on the edge of town has been converted into the headquarters of Allcom, a company that seems to be an unholy marriage of Microsoft, Monsanto, and GE. On one side of the soundstage is the bio lab, a rainforest of orchids and bromeliads and water lilies and trees reaching up to the ceiling, interspersed with catwalks and robot arms. This is Uma’s domain. On the other side, behind an enormous door, is the computer lab Ben is about to disappear into. When he emerges, three years later, it will be with his memory wiped. But on his way in, he captures Uma’s attention. Mischievously, she hits him with a blast of air almost strong enough to bowl him over. “I give up! I give up!” he cries, slicking back his hair. In a flash a robot arm swings in front of him, halting an inch or two from his face. In its pincers, a yellow orchid.

“Don’t give up,” Uma says softly.

There are plenty of action sequences in Paycheck—a motorcycle chase through the streets of Vancouver, a climactic fight scene replete with explosions, gunfire, and people diving through the air. But for Woo, that’s not the point. Woo made his name in Hong Kong in the ’80s with hyperviolent cult films like A Better Tomorrow and The Killer—maximum spatter rendered with balletic grace. Transplanted to Hollywood in the ’90s, he graduated to big-budget action-adventure tales, most notably Face Off and Mission: Impossible 2, the second-highest-grossing film of 2000. But like other genre directors, he dreams of greater things. “Paycheck is a suspenseful movie, but also it is a love story,” he says in heavily accented English while the crew preps the next shot. “Usually, science fiction movies are pretty cold. I am trying to make this one more human. Some of the scenes are a tribute to”—he claps a hand over his mouth, pretending he’s afraid to utter the word—”Hitchcock.”

Woo cites Hitchcock—along with ’30s musicals, Francis Ford Coppola, and the blood-soaked Westerns of Sam Peckinpah—as a major influence. “Hitchcock’s movies are so precise,” he says admiringly. “Every shot is calculated. And they’re not only about suspense—I also find them very romantic.” He mentions the scene in The Birds when Tippi Hedren is driving to meet Rod Taylor, a pair of lovebirds in a cage on the floor: There are lovebirds in Paycheck, too. He mentions the scene in North by Northwest when Cary Grant is chased by a crop duster in an Indiana cornfield: In Paycheck, Affleck is chased by a train. “Ben plays an ordinary man, not a superhero,” Woo says. “Just like a young Cary Grant—that’s how I want him to be.”

Dick appeals to studio execs because the humans take precedence over the science fiction — the robots, the gizmos, the spaceships that take you to Mars. The ideas are a bonus.

“This is a part I went after really aggressively,” says Affleck. “I’ve always been a fan of Philip K. Dick, both his writings and the movie adaptations. They’re big-budget movies for smart people.” Too often, Affleck admits, that’s an oxymoron: “There’s a tendency to dumb these movies down—they’re spending so much money on them, and conventional wisdom dictates that you have to go for the lowest common denominator. But his ideas prevent that. To anybody who’s ever thought, Did that happen or did I dream it?—you’d have to have a PhD in philosophy to get too deep into this, but it has to do with wanting to validate our own first-person experience.”

Just as Spielberg was dismissed by hardcore Dick fans, Woo strikes many as unworthy. They probably don’t realize that the Matrix series contains almost as many references to Woo as to Dick. (Fluttering pigeons heralding a fight, a shooter with two guns blazing—pure Woo.) And though he makes exceptions for Star Wars and Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Woo thinks most science fiction is limited in scope.

Ben Affleck: “I’ve always been a fan of Philip K. Dick, both his writings and the movie adaptations. They’re big-budget movies for smart people.”

But then, so did Dick. In response to a 1969 “questionnaire for professional science fiction writers and editors,” Dick described SF’s greatest weakness as “its inability to explore the subtle, intricate relationships that exist between the sexes,” adding that as a result it “remains pre-adult, and therefore appeals—more or less—to pre-adults.” The male-female relationships in Dick’s work tend to be more dysfunctional than romantic, but the idea of Woo interpreting Dick through Hitchcock makes sense: These are three genre artists who’ve transcended their category. Certainly if Hitch had tackled science fiction, his trademark combination of paranoia and suspense would have fit Dick perfectly.

Philip K. Dick appeals to Woo, and to studio execs as well, because the humans take precedence over the science fiction elements of his stories—the robots, the gizmos, the spaceships that transport you to Mars. The ideas are a bonus, though in “Paycheck” and other early pulp-fiction stories, they’re not always well developed. “One thing he didn’t go into,” observes Dean Georgaris, who wrote the Paycheck screenplay, “is what kind of person would agree to have a large portion of his memory erased. For me, that was the key that opened the door to the movie. It’s about what’s important in life—is it the great moments, or the little things that add up?” But the big question Dick only hinted at was what people would do if they had the machine Jennings built before his mind was wiped—a machine whose nature only gradually becomes apparent in the movie. “Would we become addicted to it, like we’ve become addicted to TV?” Georgaris wonders. Movies like The Terminator and The Matrix are about machines that attack humans. The more likely scenario, Georgaris thinks, is that humans will submit voluntarily.

[Main article continues below]

The Hollywood Treatment

Why do filmmakers love Philip K. Dick? Credit his mix of head-spinning imagination and high-concept action—not to mention big fans like Tom Cruise. Of course, Dick’s paycheck was a bit smaller. Here’s a breakdown of Philip K. Dick movies so far.

Harrison Ford in “Blade Runner”

| BLADE RUNNER (1982) |

TOTAL RECALL (1990) |

SCREAMERS (1996) |

IMPOSTOR (2002) |

MINORITY REPORT (2002) |

PAYCHECK (2003) |

|

| PLOT | A bounty hunter chases down and kills remarkably human androids, then begins to suspect he might be one himself. | A man tries to take a virtual vacation on Mars, only to learn he’s actually a secret agent fighting a brutal dictatorship there. | An army commander on a distant planet battles androids that can be distinguished from humans only by their screams. | A scientist who has developed killer androids is arrested and charged with being one. | A police officer in a unit that captures murderers before they strike is then accused of a future crime himself. | An engineer whose memory is erased races to find out why he traded a huge payday for seemingly useless trinkets. |

| DIRECTOR | Ridley Scott | Paul Verhoeven | Christian Duguay | Gary Fleder | Steven Spielberg | John Woo |

| STAR | Harrison Ford | Arnold Schwarzenegger | Peter Weller | Gary Sinise | Tom Cruise | Ben Affleck |

| GROSS (US) | $28 million | $119 million | $6 million | $6 million | $132 million | opens Dec. 25 [$54 million] |

| BASED ON | Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) | “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale” (1966) | “Second Variety” (1953) |

“Impostor” (1953) | “The Minority Report” (1956) | “Paycheck” (1953) |

| WHAT DICK GOT PAID | $1,250 |

NA |

$375 |

$75 |

$130 |

$195 |

Uma Thurman as Rachel: “I wouldn’t trade our time for anything. It’s all we are: the sum of our experiences.”

IT MAY BE FOR THE BEST that Dick’s career in Hollywood took off only after his death, because he’d certainly have had a hard time handling it in life. Psychologically, the guy was a mess. His fear of going out in public was so bad it’s difficult to imagine him taking a meeting at a film studio. According to Isa Dick-Hackett, one of three children he produced in five marriages, he couldn’t even make good on a promise to take her to Disneyland when she was little. “Twenty or thirty minutes into it, he started to complain of back pain and had to leave,” she says. “Later, I realized the crowds just freaked him out.”

The Philip K. Dick estate has no such problems. Isa and her older half-sister, Laura Leslie, are upstanding Bay Area citizens, both intelligent and obviously competent. Together with their younger half-brother, Chris, who works as a martial arts instructor in Southern California, they control their father’s legacy. Russell Galen advises them from New York. The four take their stewardship seriously: They’re fine with repackaging a novel to tie in with a movie, for example, but novelizations of short stories are out. And thanks to Vintage Books, every word of his fiction will soon be in print—as you’d expect for an author who’s now taught in colleges and cited by the French post-structuralist philosopher Jean Baudrillard.

As for film deals, the estate has become increasingly choosy. “We sort of feel like we have to protect Philip K. Dick’s brand image,” says Galen. “So we set very, very high prices, and we’ll only do business with people who are established. It’s ironic, because the films that created the phenomenon started with options that were granted to struggling filmmakers. Today, we shun people like that.” Not every movie based on Dick’s writings has been a hit: The 1996 film Screamers, starring Peter Weller, and last year’s Imposter, with Gary Sinise in the lead, grossed only $12 million between them. “But in Hollywood, what matters is getting the movie made,” explains Galen. “If somebody options a story and it’s not made, that spoils the track record.”

Dick’s kids grew up poor—no health insurance, clothes from Goodwill. While Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke were writing best-sellers, he felt lucky not to be getting rejection slips.

Still, most Hollywood writers, even successful ones, live mainly off properties that are sold but not developed, and the Dick estate is no exception. Of the more than half-dozen film projects currently in the works, some are inching forward while others are caught in limbo. John Alan Simon, who produced The Getaway with Alec Baldwin and Kim Basinger, and his partner, Dale Rosenbloom, are trying to get studio backing for films based on three Dick novels—Radio Free Albemuth, VALIS, and Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said. Miramax has a script and is looking for a director for “The Short Happy Life of the Brown Oxford,” a story about a shoe that comes alive. (“With the right actor and the right filmmaker, it will be memorable,” says development exec Michael Zoumas. “Without them it will be, what were they thinking?”) Both Joel Silver’s Time Out of Joint and Steven Soderbergh’s A Scanner Darkly are idling while the producers work on other projects. As Galen puts it, “To have Minority Report and Paycheck back-to-back like that”—big-budget films with big-name stars and a top director—”requires an incredible planetary alignment.”

Dick’s kids grew up poor—no health insurance, clothes from Goodwill. Laura recalls how grateful she was to get braces. But the hard-scrabble life was critical to Dick’s sensibility. “Phil’s work came out of an atmosphere of want and struggle,” Galen observes. Science fiction was a ghetto in the ’50s and ’60s, and Dick was one of its least fashionable residents: While Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke were writing best sellers, he counted himself lucky not to be collecting rejection slips. “From the day he wrote his first story, he was worried would he ever get another sale,” Galen says. “Certainly he was as prolific as he was because he needed money. We have 30-odd Philip K. Dick novels and not 10 because he was not that well paid.”

How celebrity would have affected him is a different question. “He would never have been that Hollywood thing, ever,” says Laura, sitting with Isa on the patio of Spago in Palo Alto. The closest he came was buying a sports car, shortly before he died. But he was afraid to drive it, and apparently with good reason: “6,000 miles, and it had dents all over it,” Laura observes. In most ways, they agree, he wouldn’t have changed. He wouldn’t have gotten health insurance. Instead of filing his income taxes, he’d have continued to claim he was handing everything over to “Mrs. Frye” at the IRS. (As far as the daughters know, Mrs. Frye never existed.) This is a guy who had to have a friend take Isa to the toy store because he couldn’t handle the anxiety. “The thought of the general public knowing who he was,” she says now—”he would have been out of his mind.”

Laura’s world was full of Philip K. Dick moments. “That was just my dad. The concept of alternate realities—I thought that was the way everybody talked.”

As things turned out, he never had to worry about it. Instead, it’s Laura and Isa who deal with his fame. The two daughters had quite different upbringings, and as primary guardians of the estate they play equally divergent roles. Laura, trim and proper and blond, saw her father only four times after the age of 3, but she read all his books when she was 12, and the two corresponded and talked on the phone constantly. Today she shuns publicity and focuses on the deals. Isa was brought up in a fundamentalist Christian home; every book her father sent was burned because it contained swear words. Outgoing and enthusiastic, with dark curls cascading almost to her shoulders, she likes to reach out to the fans. Now, for example, she’s working with Jason Koornick, who runs the fan site PhilipKDick.com, to convert it into an official one—a place where they can post unpublished letters and other documents.

Neither of the daughters was prepared for the Spielberg effect. “The whole Minority Report thing blew us away,” says Laura. “It was so unexpected”—the hubbub of the New York premiere, the glamorous party at Cipriani, the effusive praise from stars like Tom Cruise and Colin Farrell. “We didn’t realize what a phenomenon our dad was.”

“He’s a question on Jeopardy!” Isa interjects.

Laura recalls a Dean Koontz story that contains a remark about “having a Philip K. Dick moment.” She finds the notion a little unsettling: Her world was full of Philip K. Dick moments. “That was just my dad,” she says. “The concept of alternate realities—I thought that was the way everybody talked.”

In his 1974 novel Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said, Dick wrote about the sudden shift experienced by Jason Taverner, a world-famous talk-show host who wakes up one morning to find that no one has heard of him and no record of his identity exists. Dick’s own experience of celebrity is almost the reverse: For decades, no one outside the science fiction ghetto had heard of him, and now he’s world-famous, the kind of guy Tom Cruise and Steven Spielberg talk about on Oprah. All this fame came at the stage in life when he was best able to handle it—after he was dead. “I feel so happy for him,” Isa declares. “He was so afraid of death—and how amazing for him.”

“He’s going to live forever,” says Laura, continuing Isa’s thought.

“Every day, more and more people know him.”

“He transcended death,” Laura says, a note of wonder in her voice—half awe, half bemusement. As if to say: How very Philip K. Dick. ◆

Reality Check

Uma Thurman on the surreal world of Dick, karmic paybacks, and working with mind-bending auteurs.

December 1, 2003

December 1, 2003

“IT’S ALL VERY BUDDHIST,” says Uma Thurman, sitting in a dressing room as a makeup artist dabs at her face. She means Philip K. Dick, of course. Her father, Columbia University professor

“IT’S ALL VERY BUDDHIST,” says Uma Thurman, sitting in a dressing room as a makeup artist dabs at her face. She means Philip K. Dick, of course. Her father, Columbia University professor