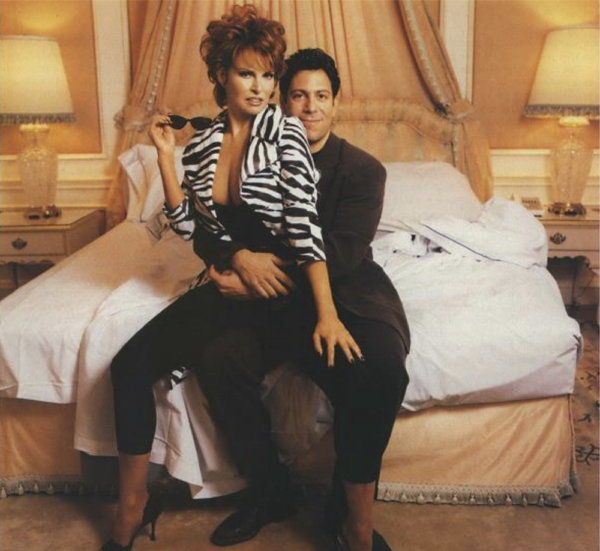

Strange Bedfellows: CBS threw out his premise and his demographics, but Darren Star was still holding on. Photograph by Timothy White

IT WASN’T SUPPOSED TO BE this way. When Darren Star, the shaggy-haired young creator of the television hits Beverly Hills 90210 and Melrose Place, landed his seven-figure, thirteen-episode, no-questions-asked deal with CBS, he was supposed to bring people with him. Not just people, but young people—viewers in the free-spending, hard-to-reach eighteen-to-thirty-four demographic. This was the “Ponce de León of prime time,” and CBS—long a haven for the gray-haired and the forgetful—was ready to step up to the fountain and drink. Yet here we are in a little patisserie in Greenwich Village, talking about Central Park West, the dud of the season, and Darren is understandably defensive. “I can only take so much responsibility for anything,” he says. “I can’t get people to turn on their television.”

Only last summer, in the weeks leading up to its premiere, Central Park West seemed unstoppable. Billboards crisscrossing Manhattan on buses, flashy promos on CBS and MTV, fawning spreads in glossy magazines, a gathering buzz among the media elite, Hard Copy vans parked outside the production office—all heralded the imminent arrival of the latest Darren Star production, a look at the high-glam/hot-sex/big-money world of New York City magazines. Helicopter rides to the Hamptons! Jogging in Central Park! A fashion editor who handcuffs her boy toy to the bedpost! Here was the show to put sparkle back into the sadly tarnished Tiffany Network, a distant third in the ratings, shorn of its record labels and many of its best affiliates, brutalized by Rupert Murdoch and his upstart Fox Broadcasting Company, hemorrhaging executives and talent, just sold to a Pittsburgh parts conglomerate by a billionaire who’d milked it for cash while its lifeblood spiraled down the drain.

Then the numbers came in.

Central Park West, which people inside the production were giddily saying might be watched by 22 percent of all viewers, debuted instead to a miserable 12 share. The following week, it got only a 9 share, a mere 5.75 million households. Watch Mariel Hemingway play the wooden-faced editor of a supercool magazine while vacuous nonentities slide carnally to the floor all around her? No, thanks.

Not that Central Park West was the only debacle on CBS. Eleven new shows were unveiled last September; eight of them tanked. Two weeks into the season, CBS was actually in fourth place, trailing Fox. The other networks weren’t doing so well, either: With more new shows than ever and viewership dropping to an all-time low, this was the most dismal season in broadcasting history. But because it had been so relentlessly hyped, the centerpiece of a much-ballyhooed CBS campaign to grab the younger viewers whom advertisers pay a premium to reach, Central Park West was the flop that defined the season. Here was a case study in cluelessness.

Six weeks after Central Park West went on the air, the folks at CBS Entertainment—the division in charge of prime-time programming—ordered some changes. As Star, still boyishly enthusiastic at thirty-four, explains it, “The network sort of said, ‘We don’t want the show to be about young people, we don’t necessarily care if it takes place in a magazine, we don’t necessarily want your leading lady on it anymore,’ and it’s like, whoa! I’m thinking the whole premise of the show is getting thrown out the window.

“I dunno. You lose the whole pretext for my coming over to CBS. Now what?”

IT WAS SPRING 1994, AND CBS WAS SEEMINGLY on a roll: It was number one in daytime and late night, and with hits like Murphy Brown and Northern Exposure, its prime-time lineup had shot from the bottom to the top and stayed there for three straight years. Yet its triumph was illusory. More households were tuned to its shows than to those of the other networks, but they were the wrong households.

Madison Avenue has been preoccupied with youth since the fifties, when CBS and NBC were the established networks and ABC was the upstart that appealed to young families. So while CBS delivered older viewers, many of them in rural areas, ABC convinced advertisers that its unformed young Levittowners were more desirable. CBS remade itself once, in the early seventies, when then-president Robert Wood decided to “get the wrinkles out” by canceling such older-skewing hits as Mayberry, R.F.D. and The Beverly Hillbillies. Wood was lucky: He picked up All in the Family, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, and M*A*S*H. But his success was short-lived.

CBS has tried to persuade Madison Avenue ever since that twenty-five to fifty-four-year-olds—its natural constituency—are a good buy: that older people have more discretionary income, that their buying patterns aren’t necessarily locked in, that the baby boomers will soon start hitting fifty. Network execs peddled the company line tirelessly. No one was buying.

“Everyone is aware of the graying of America,” says a senior executive at a large New York advertising agency. “But most advertisers also know that older viewers are the heaviest consumers of network TV. So you target the most elusive end of the audience spectrum on the theory that you’re going to get older viewers anyway.” For CBS, this meant that Murder, She Wrote was barely breaking even while ABC’s Superman update, Lois & Clark, which averaged about 10 share points fewer in the same time period, earned two and a half times as much money.

The 1994 affiliates’ meeting was a turning point. Murdoch had outbid CBS chairman Laurence Tisch for rights to the National Football League games, a staple of CBS programming since 1956. A major station group, with affiliates in Milwaukee, Detroit, Cleveland, Atlanta, Dallas, and Phoenix, had just gone over to Murdoch’s Fox network. Even though CBS was once again number one, the remaining affiliates were unhappy because the demographics were dragging down their ad rates for news and other local shows. The sales force had been saying for years that Madison Avenue wanted youth. Finally, Tisch was ready to listen.

To Peter Tortorici, a network veteran who’d just been named head of CBS Entertainment, the task seemed doable. Programmers are like tailors, one network exec joked: You want cuffs, you get cuffs; you want a bigger waist, you get a bigger waist; but you have to tell us what you want. So Tortorici started retailoring the schedule to accommodate the eighteen to thirty-four-year-olds. It was assumed going in, he says, that CBS would drop to number three in households and stay there for several years. “To avoid third place was no longer the mission. To start to broaden the audience—that was the mandate I was given.”

All this took place within a larger debate at CBS, one over brand identity. Television networks, the thinking goes, have their own images, just like the minivans and soft drinks that are hawked on them. In the future, as channel choices continue to multiply and technology enables us to see what we want when we want, the networks’ scheduling function will disappear and the only thing they’ll have to draw viewers with will be brand identity. “Ultimately, it’s not about what’s on at eight,” says Larry Sanitsky, who became Tortorici’s deputy. “It’s, Do you want to watch a Disney show or a CBS show? Central Park West was what CBS was aspiring to be.”

But changing your identity is more difficult than retailoring a suit. Many in Hollywood feel that in assuming that it could grab younger viewers without turning off its older audience, CBS succumbed to a bad case of hubris. “Central Park West,” says Sandy Grushow, who was president of Fox Entertainment when Star left for CBS, “really is the monument to all this.”

BEHIND CENTRAL PARK WEST LIES THE SPECTER of Fox. Much as ABC targeted young viewers with no network loyalties in the fifties, 20th Century-Fox chairman Barry Diller used youth-oriented shows—The Simpsons, In Living Color, Married… with Children—to make Fox a viable fourth network in the late eighties, creating in the process a brand identity that was edgy and contemporary. Diller, a graduate of Beverly Hills High, had long nurtured the idea of a series set in his old school. To create it, he turned to Aaron Spelling—the sexagenarian creator of Charlie’s Angels, The Love Boat, and Dynasty—then widely regarded as washed-up. Diller wanted to throw him a bone; he had just canned Spelling’s latest pilot, but the two of them went back to the sixties, when Diller was a fledgling ABC exec and Spelling was producing hits for the network. Spelling says he told Fox he didn’t know how teenagers thought, but Fox had someone else to worry about that—a twenty-eight-year-old film writer named Darren Star.

A UCLA grad from the upscale Washington suburb of Potomac, Maryland, Star had grown up addicted to screens— movie screens, television screens, trade papers that report on the business of screens. He saw the show as a chance to make thirtysomething for teens, a series that would tackle the big questions of high school—drinking, condoms, pregnancy, AIDS—head-on. Unfortunately, Beverly Hills 90210 languished in the Nielsens for months as Spelling, Star, and executive producer Charles Rosin—brought in to make up for Star’s lack of experience—struggled to find the right balance. “But with Fox, there was always this sense that it wasn’t a real network,” Star recalls. “It was like, well, we have nothing else, so we’re leaving you on.”

Then Fox decided to relaunch the show in midsummer, when the other networks were airing reruns. By August, thousands of screaming high school girls were turning out to meet Jason Priestley and Luke Perry, the resident heartthrobs. “That taught me a lesson,” says David Stenn, a writer and producer on the show, as he’d later be on Central Park West. “Don’t ever assume that the way something begins is the way it will end.”

“Was the hype too much?” asks Star. “Perhaps. Misdirected? I dunno.”

Next came Melrose Place, a serial drama about a bunch of free-floating twentysomethings in a cheapo West Hollywood apartment court. The premiere drew good numbers, but when subsequent episodes collapsed, Rupert Murdoch was ready to pull the plug. Fox execs went into a huddle, though, and their efforts to turn a formless ensemble show into an oversudsed nighttime soap are said to have sparked a bitter protest from Star. Not until late in the season, when Spelling star Heather Locklear brought her blond bitchery to the cast (despite Star’s vehement objections, some say), did the show begin to click.

Insiders saw little to suggest that Star should strike out on his own. “Darren has limitations as a writer,” says a former colleague. “So many people were responsible for his shows that it’s hard to say that everything he touches goes to the moon.” From the outside, however, it didn’t look that way at all. From the outside, it looked as if Darren Star had given Aaron Spelling a much-needed collagen injection. Maybe he could do the same for CBS.

“DARREN WAS EXHAUSTED,” recalls Nancy Josephson, Star’s agent at International Creative Management. Rich—with a sprawling hacienda in the Hollywood Hills and a Range Rover in the driveway and millions coming in from royalties and merchandising fees—but exhausted. He was resting up on the Mediterranean when Josephson phoned him with big news: She’d pitched CBS on a new series, and it had come back with an offer for thirteen episodes. Spelling was also after Star to renew his contract, which was expiring just as the networks’ lust for the eighteen-to-thirty-four demographic was reaching a frenzy. “There was a lot of heat on him,” Josephson explains—so much heat that he had to fly home and take meetings.

It was June 1994, weeks after the about-face at CBS. “Running a network is like culture surfing,” explains Sanitsky. “You’ve got to keep paddling out there and hope you catch a wave. Darren is not a bad surfboard to have.” CBS was willing not only to commit to a series, any series, but to provide deficit financing—to cover the difference between what the network would pay to license the show and the actual cost of making it. Star wouldn’t need a well-heeled middleman like Spelling to cover his losses while waiting for a payoff years later in the rerun market. And psychologically, he was ready to leave.

“It struck me that Darren felt he had something to prove,” says Grushow. “I don’t know if it was to himself or to others.” And where better to prove it than at CBS, where he’d be doing the show that would remake the network?

Here was an opportunity for culture surfing at its finest: L.A. = old (earthquakes, riots, fires, floods). N.Y. = bold! Abandoning the sunny-Califomia locale of his first two shows, Star quickly developed a serial drama built around a glamorous Manhattan magazine and its youthful staff—a jaded little rich girl nightclub columnist and her JFK Jr. lookalike brother, a fresh-from-Seattle editor and her hopeful novelist husband. “It seemed to capture the next thing,” says Sanitsky. “For us, it was a way into a more urban thing, too”— the factor that distinguished NBC hits like Seinfeld and Friends.

Star, who’d lived in New York briefly before and always felt slightly cheated at being called back to Los Angeles, quickly settled into a soaring triplex loft in the Village with his golden retriever, Judy, and began hanging out with boldface names like author Bret Easton Ellis. Working in New York gave him a limited pool of TV actors and writers, but it also gave him first shot at Mariel Hemingway, whose husband is a New York restaurateur. He was thrilled when they landed her.

CBS execs were equally happy when they saw the first episode last May. “It had a very big eye-candy quality to it,” says Sanitsky. “You looked at those sets, the city, the people, the clothes—I said afterward I wanted to go shopping.” The new schedule got a guardedly positive response from advertisers; that June, CBS sold some 88 percent of its available air time for the coming year, almost as much as ABC or NBC.

Meanwhile, the network was foundering, its president jumping ship, its prime-time lineup slumping back to third place. And by June, Tortorici was out. For weeks, Larry Tisch had been talking with Leslie Moonves—the head of Warner Bros. Television, the studio that made ER and Friends for NBC—about taking over CBS Entertainment. Moonves, at forty-five the most successful development exec in television, was a great catch, especially with Tisch positioning the network for a sale. But before Moonves could be extricated from his contract, Tortorici got word of the deal and resigned.

For six weeks, CBS Entertainment was left with no one at the top—six weeks during which it was developing a razzle-dazzle marketing campaign with Central Park West as the centerpiece, even though the network’s own research suggested that it was far from an automatic hit. Nobody worried, though. “When you saw those spots, you said, ‘Wow, they really did it,’ ” says David Poltrack, chief of research. “So people stopped asking, ‘Does the product live up to the claims of the promotion?’ ”

CPW, its sets and production offices stacked into four ratty-looking floors of a Greenwich Village loft building, was moving ahead in a blur of excitement. Mariel was a dream—a tad limited in her range, perhaps, but delightful to work with. Over Labor Day weekend, she and Darren even threw a party together at the beach house he’d rented in East Hampton. There was a press party at the Museum of Modern Art and a fabulous Condé Nast launch party at the Royalton Hotel and a premiere telecast on the Sony JumboTron high above Times Square.

And then, the morning after.

“I think we were all pretty shocked,” Star says of the ratings. “Really stunned that they were as bad as they were.” We’re sitting in his office, a large room whose thrown-together appearance is the antithesis of the high-gloss Manhattan fantasy the show projects. Just outside is a poster for Breakfast at Tiffany’s, one of the two films whose aura of glamour and sophistication he claims as inspiration for the series. (The other is All About Eve.) “I was happy with the show,” Star is saying. “In terms of what I set out to do, I feel like I did it. Was the hype too much? Perhaps. Was it misdirected? Perhaps. I wonder if all that hype reached the younger audience. I’m not sure.” His voice grows smaller. “I dunno.”

The idea that the hype somehow failed to connect is a popular one at CBS. Yet a top executive at a competing network says his research shows that the campaign actually reached some 70 percent of the target audience: “They just chose not to watch it.” Sandy Grushow, now president of Tele-TV Media, thinks the show’s fate was foretold by the failure the year before of Fox’s Models Inc., another wan imitation of Melrose Place. “The younger audience saw this train coming down the track,” Grushow says, “and got out of the way.”

FOR MOONVES, SETTLING INTO HIS NEW OFFICES at CBS Television City in Los Angeles, that meant the train was coming through his wall. He’d liked the campaign and the show, despite doubts they’d work on CBS. Not that his opinion mattered. “By the time I came in,” he says, “the ship had really sailed.” Now, all over the schedule, CBS shows—several of them developed by Moonves himself at Warner Bros.—were crashing. Dweebs, Bonnie Hunt, New York News, The Client—hopeless. Wednesday night, from Bless This House (Andrew Dice Clay’s dismal Honeymooners wanna-be) to CPW to the ludicrously misconceived Courthouse (Robin Givens as a public defender?), was a disaster. Sunday night, for years a CBS stronghold, was virtually wiped out by the loss of football and the decision to move Murder, She Wrote to Thursday. Older viewers, unable to find longtime favorites, were surfing over to cable, where they could at least watch reruns. Younger viewers had better things to do.

The younger audience saw this train coming. They just got out of the way.

That fall, as CPW sputtered in the ratings, Moonves and his second-in-command, Billy Campbell, did regular postmortems with Darren Star, who tried to console himself with a graph comparing CPW‘s numbers with the early returns for 90210 and Melrose. But Moonves knew the genre better—he was at Lorimar when Dallas, Knots Landing, and Falcon Crest were made there—and six weeks into the season, he concluded that the show needed a total overhaul.

Cancellation? “It was considered,” he replies. “But you don’t like striking out that quickly. You put all this time, effort, and promotion into a show, it’s on for six weeks, and you yank it; it doesn’t say much about you, your faith in your shows, or your respect for the creative community.”

The first casualty was Mariel Hemingway. “The character wasn’t taking off as our heroine,” Moonves says. “Wasn’t her fault. Lose the character.” For Star, who considered her a good friend, the news was horrible. He phoned her in Los Angeles. The show was being reconceived, he told her; her character would no longer be the lead. She could stay if she wanted, but. . .

Soon Star was back on the phone with CBS. He needed a good guy, since test audiences were saying the show had no one worth rooting for. When they suggested Gerald McRaney, the forty-seven-year-old ex-star of the CBS sitcom Major Dad, Star began to wonder. But Moonves and Campbell were adamant. “We need a CBS star,” they told him. Other producers might have walked; Star’s biggest asset, however, may be not his creative vision but his willingness to adjust it. “Television,” he says, “is very malleable.”

Star began conjuring a southern media tycoon (think Ted Turner) who comes to New York on a takeover scheme. Soon Star was culture surfing out of the gnarly waters of New York magazines and into the wide-open world of media combines, where titans rule. But while he and his writers frantically developed new characters and story lines and plotted the demise of old ones, the chaos in their offices was played out upstairs, where episode thirteen—the last of the network’s original order—was being filmed with Hemingway going out and McRaney coming in. When Hemingway said her farewell to the cast and crew, the show’s production manager burst into tears and had to leave the set.

“Who’s leaving, who’s dying—sometimes I felt like saying, ‘The camera is pointing the wrong way,’ ” recalls Ron Leibman, who plays the magazine’s owner, reprising the Roy Cohn/lizard-king characterization that won him a Tony for Angels in America. “ ‘If you wanna see a soap opera, turn the camera around.’ ”

But the real melodrama was being played out at CBS, where network executives were desperately confronting a youth strategy in meltdown. CBS had not only fallen to third in total households, it was now fourth in the all-important eighteen-to-forty-nine demographic. Moonves had already placed an order for nine more episodes—a commitment of some $12 million—when he pulled the show off the schedule in mid-November. Then, on November 30, Star got another call from Los Angeles: They’d decided to relaunch the show at midseason.

But relaunch what, exactly? Getting Gerald McRaney was one thing. “But then you have to start reconceiving the show,” Star says, flashing a toothy grin, “because who’s he going to sleep with?”

Star thought of Lauren Hutton, the fifty-two-year-old ex-supermodel who plays the socialite mom of the JFK Jr. look-alike and the evil nightclub columnist and the wife of Ron Leibman, whose media company is McRaney’s takeover target. Then he called the network and said they needed someone to stir the pot—say, Raquel Welch?

As one of the great sex symbols of the sixties, underemployed of late but smashing to look at, Welch figured to be a pull with the baby-boomer constituency: “She’s the icon of that demographic,” Star declares. “More than anybody.” Within days, he and his writers gave McRaney a greedy, manipulative ex-wife who flies in unannounced from Monte Carlo.

Moonves deflects criticism like a tank. “You don’t have to be hip to be young.”

“You could say I’ve been studying up for this part all my life,” Raquel says breathily, her voice a velveteen purr with muscle underneath, “which in some circles would be agreed upon all too quickly.” She’s probably thinking about that New York Post item that accused her of snapping her fingers at the crew and demanding a couch for her dressing room instead of a futon. “Racula,” they took to calling her on the set. But that little unpleasantness seems far away as we lounge in the flower-bedecked lobby of the Mayfair Hotel in New York, sipping tea.

It’s been snowing for two days now, but Raquel, svelte and glowing at fifty-five, is looking quite comfy in an oversize cotton sweater, black tights, and fur-covered Billy Martin après-ski boots. “I know what you’re going to say—that these are the boots from One Million Years B.C.,” she quips, referring to the 1966 caveman epic in which she wore a fur bikini—an evolutionary leap of stunning proportions.

Actually, I’d been wondering where she’s been all these years. For someone so iconic, la Welch has starred in surprisingly few hits: There was Fantastic Voyage, of course, and Myra Breckinridge and The Three Musketeers, but mostly she is famous for being famous, the California sex goddess whose impossible beauty and instant popularity were taken as proof that she couldn’t act.

“I was coming in at a time when women were in a certain mold that was epitomized by Marilyn Monroe,” she says. “That was the swan song of a certain kind of submissive woman, a woman who was there to please. From that point on came the woman you had to deal with. I’ve been the woman you have to deal with. The sex symbol you have to deal with.” She fluffs her hair, which is spiky yet bouffant.

Just as Joan Collins turned up on Dynasty late in the first season as Alexis Carrington, so Raquel Welch is set to materialize on Central Park West, as the spiteful ex who tangles with McRaney, dallies with Leibman, and goes mano a mano with Lauren Hutton. As David Stenn puts it, “We hope they’ll become the Alexis and Krystle of the nineties.”

So much for the youth strategy that was supposed to reposition CBS.

May 1, 1996

May 1, 1996