This is an expanded version of the interview that appeared in WIRED 15.06

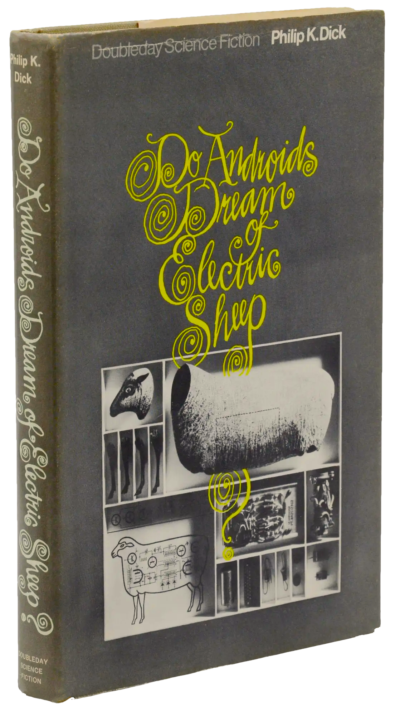

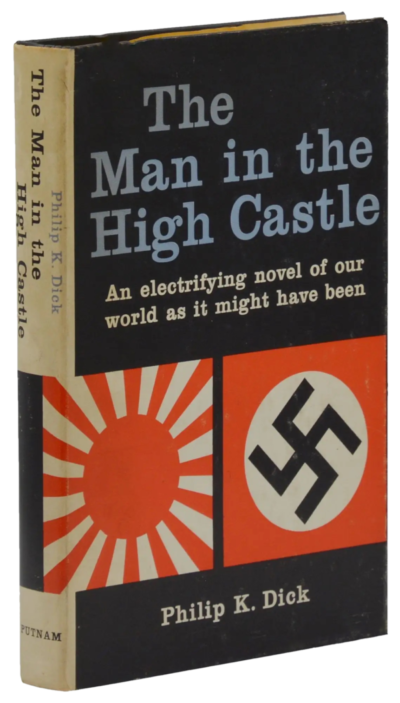

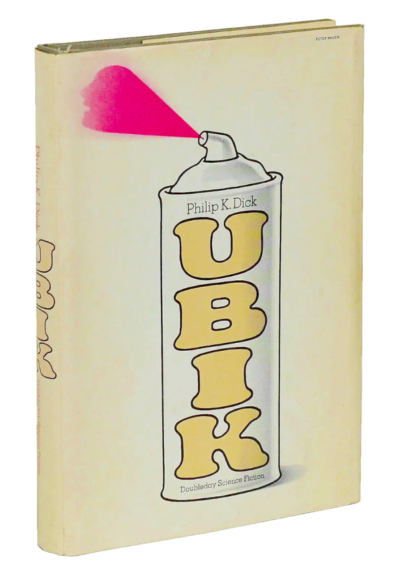

IT’S OFFICIAL: With the Library of America’s publication of Philip K. Dick: Four Novels of the 1960s, the most outré science-fiction writer of the 20th century has finally entered the canon. Yet this volume—edited by Jonathan Lethem, the Brooklyn novelist and MacArthur fellow whose own early fiction owes a lot to Dick’s—is a lit fuse to the orthodoxies of convention. The Man in the High Castle (1962), Dick’s coolly rendered imaginings of Japanese-Nazi confrontation in occupied America, was his breakthrough work. The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (1965) and Ubik (1969) established him as one of the most hallucinatory yet insightful critics of late-capitalist American civilization. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) became the basis for Blade Runner, the film that ultimately made him famous. WIRED caught Lethem as he was promoting his latest novel, You Don’t Love Me Yet, to ask about this sanctification of Dick’s oeuvre—or as Lethem once called it, his “irv.”

IT’S OFFICIAL: With the Library of America’s publication of Philip K. Dick: Four Novels of the 1960s, the most outré science-fiction writer of the 20th century has finally entered the canon. Yet this volume—edited by Jonathan Lethem, the Brooklyn novelist and MacArthur fellow whose own early fiction owes a lot to Dick’s—is a lit fuse to the orthodoxies of convention. The Man in the High Castle (1962), Dick’s coolly rendered imaginings of Japanese-Nazi confrontation in occupied America, was his breakthrough work. The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (1965) and Ubik (1969) established him as one of the most hallucinatory yet insightful critics of late-capitalist American civilization. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) became the basis for Blade Runner, the film that ultimately made him famous. WIRED caught Lethem as he was promoting his latest novel, You Don’t Love Me Yet, to ask about this sanctification of Dick’s oeuvre—or as Lethem once called it, his “irv.”

ROSE: Vintage has some three dozen Philip K. Dick novels in print. Why collect a few of them here?

LETHEM: For a great writer, the marginal stuff should be available—and I believe Dick’s a great writer, so that’s fine. But because Dick was so prolific and there’s been such an appetite for his work, Vintage has reached into the furthest reaches of his “irv” and put them in this irresistible package, so the masterpieces nestle up alongside books that Dick himself might have been horrified to see back in print. So you cringe on behalf of the potentially receptive reader who has earnestly wandered over to the shelf and come away with Dr. Futurity or The Cosmic Puppets instead of the kind of books we’re collecting in this volume, or the other titles I would argue over when I have these impossibly geeky which-books-would-you-take-to-a-desert-island conversations. Believe me, Dr. Futurity does not come into those conversations. So it can be a real turnoff. And that’s what you’re afraid of—someone who’s ready to be converted, but instead of picking up The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch or Martian Time-Slip, they’ll get one of those 1950s novels.

ROSE: Many of his short stories from the ’50s are wonderful. What was it that made his early novels so bad?

LETHEM: It’s not that there aren’t any good novels from the ’50s. There are things to be said for his first novel, Solar Lottery, and Time Out of Joint is a masterpiece. But the real reason the ’50s books are so bad is because his creative energies were elsewhere. There’s a handful of books Dick wrote while holding his own nose as he was expending very serious energies on these unpublished realist novels. It’s an oversimplification, but one compelling argument you can make for Dick is that what happened with The Man in the High Castle and then Martian Time-Slip and then Stigmata and so many others so quickly was that he unified what had been two avenues of pursuit. He invigorated the science fiction motif with all of the emotion and ambition that he’d been reserving for his mainstream efforts. It’s by feeding all his effort into one stream that he suddenly vaulted up to this other level.

LETHEM: It’s not that there aren’t any good novels from the ’50s. There are things to be said for his first novel, Solar Lottery, and Time Out of Joint is a masterpiece. But the real reason the ’50s books are so bad is because his creative energies were elsewhere. There’s a handful of books Dick wrote while holding his own nose as he was expending very serious energies on these unpublished realist novels. It’s an oversimplification, but one compelling argument you can make for Dick is that what happened with The Man in the High Castle and then Martian Time-Slip and then Stigmata and so many others so quickly was that he unified what had been two avenues of pursuit. He invigorated the science fiction motif with all of the emotion and ambition that he’d been reserving for his mainstream efforts. It’s by feeding all his effort into one stream that he suddenly vaulted up to this other level.

ROSE: Why were his attempts at conventional fiction unsuccessful?

LETHEM: He was working with some disadvantages. He was such an untutored writer, and there were inconsistencies to which he was prone almost to the end of his career that would undermine a realist novel of suburban ennui but could almost be seen as an advantage in his other work. The dislocation that people suffer, the way they suddenly slip out of context into this galactic alienation—that’s not accounted for by the fact that their job is bad or their marriage is bad. It sometimes makes these novels seem very arbitrary. But he came close, and you can speculate that if one of them had been picked up by a sympathetic editor and published, as opposed to almost published, he might have applied his genius to working out some of these problems and improving the quality of his sentences.

The Man in the High Castle is as beautifully written as a novel can be, and many many sequences in the last few novels are elegantly written. He could have cultivated that if he were working in an arena where that was what was rewarded. But he worked with editors who wanted him to be a brilliant extrapolator—that was the criterion he was meeting, and he met that and then some. He became a hallucinatory extrapolator. He became extrapolatively insane, and therefore arguably the greatest science fiction writer who ever lived. The essence of his achievement is the degree of commitment, the way everything was life and death for him. For him it was all crucial. It all mattered utterly. That’s what gives his work its distinctive quality.

Read . . .

The Second Coming of Philip K. Dick

How a hyper-paranoid, pulp-fiction hack conquered Hollywood—20 years after his death.

Wired 11.12 | December 2003

ROSE: So is there an alternate reality in which he might have become John Cheever?

LETHEM: Well, I dunno. Another disadvantage is that serious writers in the western half of the country end up being boxed out of a certain kind of blue-blood—I mean Cheever was at The New Yorker. It’s hard to picture Dick figuring out what would tickle the East Coast establishment. Who can we think of who did in his generation of California writers, without coming to New York and making a commitment to the standards of the East Coast intelligentsia by dwelling among them, like Pauline Kael or Joan Didion? It didn’t really work to stay in California. But then again, you can make up a story where some editor says, “And you’ve got to come to New York.”

ROSE: How did you decide on these titles?

LETHEM: If I had to pick only one novel for someone to read, I think my head would explode. The best novels—and I think there are ten or fifteen of those—collectively form one of the greatest bodies of work in American literature, and yet no single novel or even two or three novels even begin to suggest just how rich and deep it goes. They accumulate power enormously. And I have a lot of dark-horse favorites, books I think are undervalued. Martian Time-Slip and Dr. Bloodmoney in particular are right at the level of the four books I picked. But the Library of America really is the American canon, and it’s probably not the place to be showing off your erudition by advocating for a dark-horse candidate. There’s a level at which acclaim becomes self-reinforcing. I think Martian Time-Slip is the equal of The Man in the High Castle, but The Man in the High Castle has a greater meaning in Dick’s career and in the history of American science fiction because of the award [the 1963 Hugo Award for best science fiction or fantasy novel] and the way it changed his career and the way academics have gravitated toward that book to write about. Its meaning was created partly in the reception. So I reached for the books that were the unmistakable classics.

ROSE: Why is this volume restricted to novels of the ’60s?

LETHEM: If we were only going to do four novels, I wanted to at least create the possibility of doing other volumes for other phases of his career. In picking those four novels from the ’60s, I was certainly not surprising anyone. But the important curatorial work was earlier than that, in arguing strongly that there ought to be a volume for the ’60s, which implied strongly that there ought to be a volume for the ’70s. So rather than pick three of the ’60s novels and A Scanner Darkly, let’s say, by carving out a decade of his career I’m reserving I hope the opportunity for there to be a look at the ’70s work. There are four novels that in my mind would very naturally fit—Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said; A Scanner Darkly; VALIS; and The Transmigration of Timothy Archer. I like The Divine Invasion too, but that’s a very hermetic book. Its virtues are unavailable to people who aren’t really versed in his work, whereas the other four all make their own case. I’m really talking through my hat here because I have no license to edit a second volume, but if it came to pass you’d have eight of his masterpieces.

LETHEM: If we were only going to do four novels, I wanted to at least create the possibility of doing other volumes for other phases of his career. In picking those four novels from the ’60s, I was certainly not surprising anyone. But the important curatorial work was earlier than that, in arguing strongly that there ought to be a volume for the ’60s, which implied strongly that there ought to be a volume for the ’70s. So rather than pick three of the ’60s novels and A Scanner Darkly, let’s say, by carving out a decade of his career I’m reserving I hope the opportunity for there to be a look at the ’70s work. There are four novels that in my mind would very naturally fit—Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said; A Scanner Darkly; VALIS; and The Transmigration of Timothy Archer. I like The Divine Invasion too, but that’s a very hermetic book. Its virtues are unavailable to people who aren’t really versed in his work, whereas the other four all make their own case. I’m really talking through my hat here because I have no license to edit a second volume, but if it came to pass you’d have eight of his masterpieces.

[Lethem would eventually produce not one but two additional volumes for the Library of America: Five Novels of the 1960s & 70s — which included Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said and A Scanner Darkly as well as Martian Time-Slip, Dr. Bloodmoney and Now Wait for Last Year, centered on a reality-altering hallucinogen — and VALIS & Later Novels, which in addition to VALIS (an acronym for Vast Active Living Intelligence System, which was Dick’s concept of God) included The Divine Invasion, The Transmigration of Timothy Archer and the 1970 thriller A Maze of Death.]

ROSE: You discovered him as a teenager?

LETHEM: My friend Carl’s dad bought Carl a copy of The Golden Man. I think that was the first Philip K. Dick book I laid eyes on. I would have been 13 or 14. It feels like one of those fateful moments. I just had to know who this guy was. And my great luck was that I found a copy of Ubik in a used bookstore. That changed my life. It was like a book-length metaphor for feelings that were churning within me that were unnamed at that point. Turning the pages—all epiphany, all the time. He was my favorite writer before I finished even reading that book. My high school years were devoted to finding and devouring all of those out-of-print titles, right down to the maximally disappointing Vulcan Hammer and Dr. Futurity. And then what weird great timing for me, because VALIS was published. That was the first book of his that I got hot off the press, and it was right as I was about to go to college and beginning to think about running away to California.

I had this idea that I was going to go sit at the feet of my guru. I was very intent on it. And as I was conceiving this plan in ’81 and ’82, I got the news that he had died. So I sort of did it anyway. I was like a chicken with its head cut off—the thrust was still there, my feet moved to California, and I found Paul Williams. It’s a pretty funny thought that Paul Williams, who was so deeply of the counterculture, seemed to be the person who gave the imprimatur of the mainstream to this marginal writer, because he’d interviewed Dick for Rolling Stone and in the course of doing so called him the greatest sci-fi mind on any planet. That blurb seemed in the context of Dick’s total absence from the culture to be the greatest evidence that he had mattered. Rolling Stone? Rolling Stone!

“I don’t think it’s an accident that he was so marginal. There was something about him that was deeply fugitive.”

June 1, 2007

June 1, 2007

ROSE: Obviously your first couple of novels relate very strongly to his work. What did you discover about him in writing them?

ROSE: Obviously your first couple of novels relate very strongly to his work. What did you discover about him in writing them?