Before there was Disney for Michael Ovitz, before there was CAA, there was the William Morris Agency. Frank Rose’s book The Agency goes behind the doors of the pioneering talent agency. In this excerpt, Rose looks at the time when young eager-beaver Ovitz plotted with his fellow agents to form the Creative Artists Agency.

“YOU WERE PUT IN THE COMPUTER,” Sam Weisbord announced, “and found wanting.”

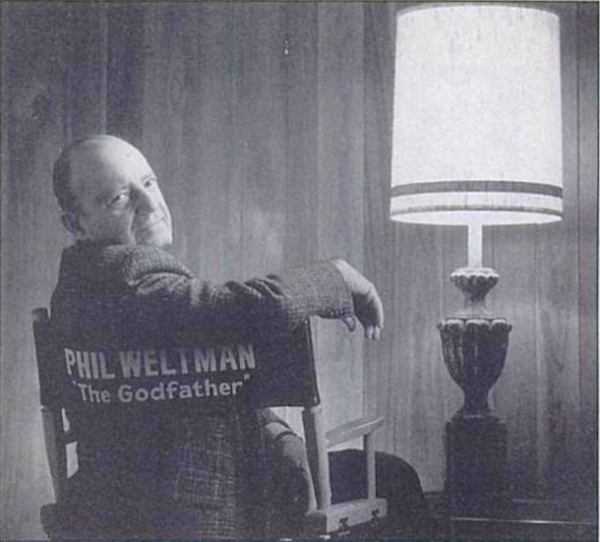

It was fall 1974, and Weisbord, worldwide head of television at the William Morris Agency in Beverly Hills, had just walked down the hall to see Phil Weltman, his best friend of nearly 50 years. Weltman and Weisbord had known each other since they were teenagers in Brooklyn. Sammy had been an eager kid, quick and ferret-like, and in 1929, when he was 17, he’d gone to work at the Morris office, where he eventually landed a plum position as secretary to Abe Lastfogel, who headed the agency until his retirement in 1969. Weltman had been with the agency since the ’30s, but he’d failed to endear himself to Nat Lefkowitz, the lawyer-accountant who’d succeeded Lastfogel. Weltman was a maverick, or so Weisbord said.

Take his response to the news that Sid Sheinberg, the 38-year-old executive in charge of Universal Television, was going to step into Lew Wasserman‘s job as president of MCA. Weltman was sitting with Weisbord and Lefkowitz when he remarked that the Morris agency ought to be thinking about getting some young people into the picture too.

What did he mean by that?

He meant they ought to pick a young guy and work with him—polish him up, make him important in the industry, groom him for the top job. Then he made a crack about how they shouldn’t be running the Morris office like the Mormon Church, whose 96-year-old president had just died and been succeeded by a 95-year-old.

Lefkowitz looked like someone had thrust a dagger in his heart. He was 68, eight years older than Wasserman. And unlike Wasserman, he’d waited 46 years to become president—46 patient, self-abnegating years of cleverly structured deals and mumbled directives at meetings and awkward silences at parties, while Lastfogel flitted back and forth between New York and the Coast, playing the star-maker to Hollywood and Broadway and Madison Avenue. Finally Lefkowitz had gotten his reward, and he didn’t want to see it cut short. And what about Sammy Weisbord, who was nearly 62 and had sat at Lastfogel’s feet from the age of 19?

There was another problem with Weltman’s boys—they were too much like Weltman. Michael Ovitz, for instance—a gap-toothed 26-year-old who’d grown up in a tract house in the San Fernando Valley and now packaged game shows for daytime TV. Ovitz had worked part time at Universal while taking his premed courses at UCLA, and in 1969, shortly after graduating, he’d gotten into the William Morris trainee program.

Ovitz wasn’t the only one loyal to Weltman. There was Rowland Perkins, 39, a packaging agent who’d gotten into the mail room through his friend’s aunt—Loretta Young. There was 30-year-old Bill Haber, the packaging agent who covered NBC, just as Perkins covered CBS and a third agent, Mike Rosenfeld, took care of ABC.

And there was Ron Meyer, a 28-year-old ex-Marine from West L.A. who had succeeded Haber as co-head of the television talent department, which booked guest stars on series at $1,500 to $2,500 a pop. Weltman had hired him away from Paul Kohner, an old-line agent on Sunset who’d handled John Huston and Ingmar Bergman for years. As a high school dropout, he would never have qualified for Morris’s training program, but Weltman had decided to take a flyer on him. Now he was almost like a son.

Within the television department, Weltman was as loved as Weisbord was despised. They made a peculiar pair. Weisbord gave stirring speeches, the kind that black-and-white movie generals delivered before sending their extras into battle, all about girding their loins and going forth to attack the enemy. Weltman was the tough guy, the grizzled taskmaster they could always count on to tend their wounds, to nurse them through thick and thin. As far as deals and commissions were concerned, his productive years were probably over. But to his department—the most lucrative branch of the agency—he was the glue that held them together.

AT FIRST, WELTMAN DIDN’T KNOW what Sammy was talking about. “Put in the computer and found wanting?” What kind of thing was that to say? As the realization that he was being fired slowly flooded his brain, he went into a kind of shock. Weisbord walked out.

Weltman sat alone at his desk, numb with despair. After 35 years together at William Morris, his best friend had just told him he was worthless. He called his boys down, one or two at a time. When he told Mike Ovitz and Ron Meyer, they made a confession: They had been thinking of going into business for themselves. They’d been planning it for months, but they hadn’t been able to tell him. This made it easy.

Ovitz and Meyer weren’t the only ones thinking about leaving. For months, Rowland Perkins, Bill Haber and Mike Rosenfeld had talked about starting their own agency. As the holidays approached, they learned that Ovitz and Meyer had the same idea.

Howard West and his friend George Shapiro had recently left the Morris agency to start a management office, and Ovitz had taken over West’s job, packaging daytime TV shows and handling the Motown account. Now he and Meyer went to West for advice. Should they join forces with the three others or go it alone? The only client they had with any name value was Sally Struthers, who played Carroll O’Connor’s daughter in All in the Family. West advised them to go with Perkins and his group. Five people forming an agency would have a broad base of clients and expertise, he told them. They’d get much more than five times as much business.

Later that month, the two groups got together for the first time at Perkins’s house in Bel-Air. The chemistry was immediate. The timing seemed right. They set a date a couple of months away. That would give them until March—time to get organized, secure a line of credit, find office space, make a graceful exit. Then they’d tell Weisbord, and because spring was television season, they’d offer to stay until the network schedules were set.

They started waking up in the middle of the night. That’s when it hit them: Their lives were about to change forever. They’d be working seven days a week, no pay, no guarantees. They were married men. They had responsibilities. Three of them had kids. But it was too late to pull out now.

The new partners at Creative Artists Agency. Front row, seated: Bill Haber, Michael Ovitz, Rowland Perkins. Back row, standing: Martin Baum, Ron Meyer, Mike Rosenbaum, Steve Roth. Photo: Los Angeles Times

TUESDAY, JAN. 7, 1975. Mike Rosenfeld got an early-morning phone call from a New York entertainment lawyer who’d been told about their plans. The message was brief and to the point: “They know you’re leaving.”

Ovitz was off on a skiing trip. Ron Meyer was lying in bed in his little apartment a block from the Morris office, immobilized by the flu. Over lunch, Rosenfeld told Perkins not to be surprised if he got a call from Weisbord. When they got back to the office, Perkins had a message: See Weisbord at once.

Weisbord had always been volatile, but this time he kept it under control. He said, very casually: “Morris Stoller [who ran the Beverly Hills office] told me he understands that five of you are leaving the company.”

Perkins stopped. “Well, Sam,” he said, “this is something we were going to come in and talk to you about tomorrow.” Not true, and Sammy knew it.

Sammy drew himself up and stood nose to nose with Perkins—or nose to chin, since Perkins was several inches taller. “Now Perkins,” he cried, “this is treason!” Ten minutes of rage ensued—why, if he’d only stopped and thought, a person of Perkins’s character. . . . Finally Perkins yelled, “Stop it!” If that’s really what Weisbord thought, he was a jerk for letting it go so long.

Rosenfeld and Bill Haber were called in later that afternoon. Ron Meyer got a phone call at home, but he was too sick to speak. No one could reach Ovitz. Rosenfeld lived nearby, so he went to his house and left a note on the door: “You’re no longer working at William Morris. Call me.”

On Friday afternoon, after talks with the agency attorney, the five defectors found themselves on the street—no desks, no telephones, no office. No clients, either. Several clients followed them over the next few weeks, but their commissions stayed at Morris until their agency contracts ran out.

The new partners secured a $100,000 line of credit from Security Pacific Bank, and on Jan. 22 they announced their name—the Creative Artists Agency. They figured that’s what they were, an agency that handled creative artists.

They found a modest spread in the Hong Kong Bank Building a few blocks away on Wilshire, and for $200 they bought some used office furniture. They got a conference table at a discount store in the Valley and brought card tables and folding chairs from home. They hired a secretary, but they couldn’t afford a receptionist, so their wives came in to cover the front desk.

Back at the Morris office, the mood was bleak. People had just seen Weltman chopped off at the knees. Now an enormous chunk had been ripped out of the television operation.

But to Weisbord and Lefkowitz, it seemed like no big deal. The only one they were actually sorry to lose was the new agency’s president, Rowland Perkins, who was also the one who brought in the most income. These guys weren’t executives, Lefkowitz announced dismissively. They were just shoe-leather agents.

SEPTEMBER 1977 WAS THE MONTH the Creative Artists Agency left the Hong Kong Bank Building for the modernistic landscape of Century City. The new offices were on the 14th floor of the Tiger International Building, headquarters of Flying Tiger Airlines—a professional-looking suite (no card tables) with a spacious sitting area by the elevator and a conference room beyond. To the right was Michael Ovitz’s office, stark and Japanese-looking, with striking Oriental vases on lacquered tables; to the left was everyone else.

Ovitz had recently taken over as president from Perkins, in line with the partners’ plan to rotate the top job among themselves every two years. But though they’d started as equal partners, Ovitz was quickly emerging as the leader. He was the most driven—dynamic and inspirational, with a hard, steely resolve and a focus on some larger prize. There was a price to success that he and his wife, Judy, seemed willing to pay. Acquaintances would see her in a restaurant at dinner time, sitting at a table alone; two hours later she’d still be there, waiting patiently. They still lived in the Valley, in a white-frame ranch house in Sherman Oaks, but that was hardly the extent of his ambition. He showed a Gatsbyesque desire to reinvent himself. If he saw an employee reading Film Comment or Harper’s or Art in America, he’d ask about it: What was this magazine? Should they be subscribing to it? Would it tell him about art? Because some day, when they could afford it, he’d want real art on the walls.

The agency functioned much like the Morris office, thanks to the lessons the five partners had learned from Phil Weltman. As they grew bigger they’d adopted the same apprenticeship program, moving trainees from mail room to secretary to junior agent. They’d duplicated the phone-sheet system, logging the day’s calls and making sure no one went home until each one had been returned. They’d embraced the dress code—suit and tie for all occasions. They’d even borrowed the William Morris temperament—buttoned-up, lawyerly in approach. They weren’t concerned with looking trendy or relaxed. They were there to get the job done.

About the only thing they hadn’t taken from Morris was clients. Their biggest stars were Sally Struthers and Rob Reiner, the young couple in All in the Family, and Talia Shire, Francis Ford Coppola’s sister, who played Al Pacino’s sister in the Godfather movies. They had Bill Carrothers, producer of The Odd Couple, and game-show producer Jack Barry, known to millions as the host of Tic-Tac-Dough and Concentration and Twenty-One, the program that epitomized the quiz-show scandal back in 1958. Recently they’d picked up Ernest Borgnine, Burgess Meredith, Debbie Reynolds and the Jackson Five, but it was still a grab-bag list, hardly anything to build a package around. And the worst of it was that most of them were still paying commissions to other agencies.

Maybe that’s why the five of them seemed to have such a siege mentality, as if it were them against the world. That was where you felt the difference between them and the Morris office—hunger. At Morris they’d been kept on a short leash; now they were free to go after anyone. It didn’t hurt that buyers were eager to break the lock of the two big agencies (International Creative Management was the other) on stars by throwing projects their way. As vice president of comedy development at ABC, Michael Eisner had worked closely with Mike Rosenfeld at Morris; after CAA was formed, Eisner put his programming execs in a room with Rosenfeld and his partners and refused to let them leave until each one had come up with a project the new agency could handle.

In October, Ovitz announced a new partner: Martin Baum. Marty Baum was a white-haired veteran, an old-time Broadway mug gone Hollywood—not the biggest name in the picture business, but a name. The stars he’d once handled were faded now—Julie Andrews, Sidney Poitier. But they were real stars, and he brought them to CAA—not just Poitier, but Dyan Cannon and Stockard Channing and Richard Harris and Joanne Woodward. He also brought writer-producer-director Blake Edwards and actor Carroll O’Connor. That fall, a skywriting plane appeared over Malibu: “Thank You Martin Baum for Joining Us—CAA.”

Baum gave them credibility. If a client had left one of the giant agencies, the new office in Century City began to look like a possibility. He helped them strategize too. A couple of years later, after a screening of New York, New York, the Martin Scorsese film with Liza Minnelli and Robert De Niro, Baum suggested they sign Diahnne Abbott, who sang “Honeysuckle Rose” in the picture. Why her? Because she happened to be De Niro’s wife, Baum explained, and anything that would get them closer to De Niro they should do.

Phil Weltman, the “godfather” of Creative Artists Agency

September 3, 1995

September 3, 1995