Jay Gorney in front of Meyer Vaisman’s “The Double Wedding Portrait.”

JAY GORNEY HAS RECEIVED a standing ovation from his staff only once. That was in February, when an Ohio businessman walked out of Gorney’s SoHo gallery as the new owner of Disco’s Bed, a room-size work by sculptor Joel Otterson. Frankly, this wasn’t the kind of piece most artists expect to sell: a rocking Craftmatic four-poster fitted out with spandex sheets, a studded silk coverlet, a studded silver lamé canopy, a mirrored ball, lights, sound, and endless Donna Summer tapes, with a $50,000 price tag and enough cultural baggage in this age of AIDS to overwhelm the average New York gallery-goer. The buyer planned to put the piece in his guest room.

The Otterson sale was hardly the most unlikely Gorney has ever made. Shortly after his gallery opened in 1985, in a tiny East Village storefront, he sold a Meyer Vaisman painting to Charles Saatchi, the British adman and collector. Titled The Dung Market, the canvas was covered with baby-bottle nipples—a gibe at rich collectors who suckle at the font of genius. He sold another nipple painting to Linda Macklowe, the wife of real-estate developer Harry Macklowe. “As a collector, I thought Meyer was very . . . interesting,” she says, groping for words. “He’s sly, and ironic, and very, very interesting.”

Art Starsand the machinery behind them. |

Cai Guo-QiangAfter working with institutions of the highest rank, from the Getty to Tate Modern, one of the most recognizable artists of recent memory is dipping more than a toe into the commercial art world.

|

WangShuiObsessed with the origins of consciousness and humanity’s preoccupation with violence, WangShui hopes that, through AI, love will find a way.

|

A ‘Holopoem’ for the CosmosEduardo Kac found an unusual public space for his artwork — orbiting the sun.

|

Making Art Out of Bombshells and Memories in VietnamTuan Andrew Nguyen’s videos and sculptures uncover haunting artifacts and stories from the Vietnam War.

|

David Byrne Is Totally ConnectedThere’s a new gallery show of his whimsical drawings — and coming this summer, an immersive art-and-science experience.

|

A.I. Meets Fatherhood in an Artist’s New WorkIan Cheng’s latest: a narrative animation powered by a game engine and partly inspired by his two-year-old.

|

Frank Gehry’s Disney Hall Is TechnodreamingData artist Refik Anadol creates a swirling projection on steel for the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

|

Alan Vega Ignored the Art World. It Won’t Return the Favor.A year after his death, the lead singer of Suicide looms over the downtown art scene.

|

The Whitney After AllThe Whitney Museum never really fit in uptown. Now it has relocated to a part of the Village that until recently was a reeking abattoir. Home, sweet home.

|

A Palace of WondersThe Panza Collection mounts a show challenging perceptions.

|

Last LaughJay Gorney sells art that sends up collectors. “They hear tom-toms in the distance,” says a curator, “and they get out their checkbooks.”

|

Cool John B.John Baldessari got rid of all the extraneous stuff, like form and beauty. Now he’s the éminence grise of conceptualism, in the spotlight at last.

|

As the Art World TurnsThe mix of art, big bucks and hype has turned the art world into a frothy soap opera. Which brings us to Julian Schnabel . . .

|

“Meyer is involved with ideas about how art is commodified, how it moves through the system, how the system mythifies the artist,” Gorney said as we sat in his small but pristine West Village apartment. “He has Freudian concerns with shit and money being the same thing.”

When Gorney’s gallery opened, Vaisman was running International With Monument, the gallery at the center of the collecting hysteria then sweeping the area. The people who showed there and at two other artist-run galleries, Nature Morte and Cash/Newhouse, had little in common with the graffiti artists, whose raw, streetwise, often overtly political work the East Village was known for. Their art was cool and calculated, with a cynical edge. Combining Conceptualism’s intellectual pretensions and Pop Art’s infatuation with consumer objects, they created avant-garde objects that lampooned the notion of art as a commodity. Extending the joke to the limit, they then sold these objects to eager collectors who took this mockery as artistic high-mindedness.

AS THE STAKES GOT HIGHER, artist-dealers like Vaisman got out of the gallery business, and Gorney ended up doing the selling. Sonnabend—a gallery that rode the first wave of Pop and Conceptualism in the sixties—got Ashley Bickerton, Peter Halley, and Jeff Koons, the stars of International With Monument, after a much-ballyhooed group show in 1986. But Gorney picked up Otterson, Nature Morte co-founder Peter Nagy, photo artist Sarah Charlesworth, and Tim Rollins + K.O.S. (Kids of Survival), a collaboration between a lower Manhattan Conceptual artist and a group of “learning disabled” teenagers in the South Bronx. Gorney shares Vaisman with Sonnabend and Leo Castelli, and shares Haim Steinbach, a commercially successful sculptor who arranges consumer items on wedge-shaped shelves, with Sonnabend as well.

Now in a more comfortable storefront on Greene Street, Jay Gorney Modern Art is a prime outlet, along with Sonnabend and Metro Pictures, for some of the most talked-about, if not widely admired, art in town. A prematurely graying 37-year-old who suggests Harvey Fierstein trapped in Perry Mason’s body, Gorney sells perhaps $2 million worth of art a year and sees it all as cutting-edge.

Rollins and his Kids of Survival “debunk the myth of the genius white male artist alone in his studio, drunk on bourbon and sincerity,” says Gorney. Steinbach—whose surrealistic displays of everything from detergent boxes to lava lamps sell for $30,000 and up, plus the cost of the objects—was recently commissioned by the Indianapolis Museum of Art to incorporate parts of its collection into one work. “There’s something very subversive about that,” Gorney said gleefully. “It’s cannibalistic to an incredible degree.”

But is it good art? At their best, Rollins + K.O.S. create moving, heartfelt work that’s drawn qualified praise even from archconservative Hilton Kramer. Some of the others are more problematic. “I think a lot of those artists haven’t progressed beyond their first idea,” says one insider.

“If you listen to the cheerleaders, you may get the idea that this art is something other than really thin and marginal,” says Kay Larson, New York’s art critic. “Way out there on Pluto, there is a crowd of people who are all congratulating each other on how important they are. But you can’t afford to get provoked and irritated, because then they’ve got you, just like in advertising. Some art these days aspires to the stature of an obnoxious aspirin commercial.”

Haim Steinbach, “supremely black” (1985)

The common denominator among Gorney’s artists—at least the more commercially successful ones—is a slick perfectionism that acts cynically and manipulatively to stimulate desire. Their twin concerns seem to be art history and shopping. Not everyone thinks that’s bad. “This art is very fetishistic, and the fetishes of the late twentieth century are well worth examining,” says Barry Blinderman, who ran the Semaphore gallery in SoHo and the East Village until he left for Illinois State University. “And the very people who are buying the work are the people who’re being commented on. It’s like Goya’s portraits of the family of Charles IV, which indicated the pomposity and vacuity of the people who’d commissioned him.”

Indeed. With Gorney as a chief pitchman, the vogue for neo-Conceptual art became the late-eighties version of radical chic. A Vaisman nipple painting or a Steinbach shelf with kitsch coffee mugs and pre-Christian pottery is infinitely more decorative than a Black Panther spouting revolutionary gibberish in the living room, and it provides an intellectual thrill as well. “You don’t have to read Baudrillard,” says Blinderman, referring to the French post-structuralist philosopher. “By owning the work of art, you’ll understand it.”

SOHO PITCHMAN

“I think my artists are great,” he says, “but I’m amazed the world is letting me do this.”

As for Gorney, having grown up fat and lonely in Flatbush, he views his career with a sense of wonder unclouded by false modesty. “I’m astounded by my success,” he said, eyeing a Vaisman self-portrait across the room—a silkscreen blowup of a Florentine street artist’s impish caricature, surrounded by an exaggerated canvas weave that burlesques the idea of painting. “I think my artists are great, and I think I’m a great dealer. But I’m amazed the world is letting me do this.”

GORNEY WAS WORRIED about place cards. He and Peter Nagy were hunched over a table in the back room of the gallery, planning an opening-night supper at Odeon. “I thought Post-It notes would be perfect,” Nagy cried. “Post-It notes on water glasses. C’mon! We’re supposed to be creative types.”

“No!” Gorney was horrified.

“You’re not gonna let me?”

“You can if you want to, Pete. But I’d strongly recommend cream-colored cards.”

Sarah Charlesworth, Self-Portrait (1989)

A slender young man with Veronica Lake hair, Nagy flaunts the Bohemian qualities Gorney lacks. At heart, however, they’re much the same. “It gave him anxiety at first that he didn’t have enough money to start a really slick gallery like Mary Boone’s,” Nagy says. “Jay and I are not trust-fund kids. But we’ve won a certain amount of financial security, and we’ve worked for it. I think he wishes his parents were here to see what he’s achieved.”

An only child, Gorney was raised by an overbearing Jewish mother on Ocean Parkway—”a real Woody Allen thing, me and my mom in Eisenhower-era Brooklyn.” But his formative influence was Warhol, not Woody. As a teenager, he saw nearly every film Warhol made; after graduating from Oberlin College, he moved to the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program and wrote a paper called “The Sensibility of Glitter in Contemporary Art.”

This won him a job at the Sidney Janis Gallery, the 57th Street gallery that showed George Segal and Claes Oldenburg. Later, he worked for Andrew Crispo. When Patricia Hamilton, a curator at Crispo, left to open her own gallery, Gorney went with her.

From 1977 until it closed under duress, in 1984, the Hamilton Gallery was a quiet place known for American post-minimalist painting and sculpture—serious work by older artists who’d never cut a high profile. Hamilton and Gorney were great friends. Gorney’s mother had just died of heart failure, and Hamilton—a brassy woman whose self-confidence contrasted sharply with his then-shy, studious demeanor—helped fill the void. But at the end of the seventies, with New Image painting and German and Italian neo-Expressionism bringing new currents into contemporary art, Gorney developed more adventurous tastes. “He could really read the pulse,” says Dan Cameron, a freelance curator-critic who knows him well. “Pat got very confused and felt left out.”

Things got worse when several members of Hamilton’s family died. The strain was obvious; Gorney was not supportive. Instead of jokes, the gallery reverberated with angry silences. “A lot of people had hostile feelings toward Jay for the way he was toward Pat,” says John Torreano, a gallery artist. “The scariest thing to Jay is to look bad,” says a mutual friend who’s known him for years. “She was too sloppy. That brought out this hostility in him which he can’t let go of.”

“It was not pleasant,” says Hamilton. “It really felt like a divorce. But I’m very happy now. I’m not bitter or angry. I think it’s very silly for him to carry around this hate torch. Whatever problems Jay thinks he has with me really have to do with himself.”

Gorney feels differently. “Not only do we have nothing in common,” he says, “but we have nothing to say to each other about contemporary art.”

AFTER HAMILTON, in a period known to friends as “Jay Gorney: The Dark Years,” Gorney gravitated toward the East Village. Attractive jobs did not materialize, so he supported himself selling art from storefront galleries to a few uptown collectors for a 20 percent commission. “The Hamilton Gallery had been what held him up as a person,” says Cameron. “For a year and a half, the big thing every morning was getting himself psyched up to say, ‘I can do something.’”

Prodded by his friend Cameron, Gorney developed a taste for Sherrie Levine, a Metro Pictures artist who was making watercolors of bookplate reproductions of paintings by modern masters such as Léger, Matisse, and Schiele. “Her work is so much about frustrated desire,” he says. “Longing for creativity, longing for authorship.” Gorney had known longing all his life—longing for family, recognition, success. He responded readily.

“He’s not in this for money,” says painter Deborah Kass. “He’s in it for love.”

Like Levine, the International With Monument crowd took a detached, Warholesque view of things. Vaisman and Koons had a deflating effect on the heroically self-important neo-Expressionist painters—Julian Schnabel chief among them—who’d become instant stars in the art boom of the early eighties. “You had this superheated Schnabel on the wall,” Gorney says, “and then you had Koons’s basketball floating in a tank.” It was perfect.

GOOD EYE

“He could really read the pulse,” says freelance curator Dan Cameron.

Gorney’s friends kept urging him to open a gallery; he resisted. He didn’t have any money. He didn’t know how to run a business. But when the gallery next to Nature Morte closed, he traded his apartment for a miniscule storefront with a loft in back he couldn’t stand up in. It was good timing: Within moments, the gold rush in neo-Conceptualism would be on.

In the late sixties, Conceptualism had been rigorously anti-commercial, a dematerialization of art that sought to escape the gallery system and the realm of commerce. This time it was different. What appeared superficially shocking was in fact shockingly luscious — just like a Schnabel. This was no accident. “All this work operates on a couple of different levels,” says Nagy. “It’s scholarly in terms of content, and very luscious and seductive to appeal to the collector market.”

Soon, limousines could be seen on the burned-out streets, disgorging collectors on the prowl: Charles and Doris Saatchi . . . MOMA trustee Barbara Jakobson . . . takeover artist Asher Edelman . . . Hollywood superagent Michael Ovitz. Gorney, no amateur, was better prepared than other East Village dealers. “When we opened Nature Morte,” Nagy says, “we felt if we offered good art at low enough prices, people would buy it. We didn’t have any idea how it really works, which is you create the demand and people will pay anything for it. We didn’t realize most collectors buy with their ears and not with their eyes.”

“They hear tom-toms in the distance,” explains a curator, “and they get out their checkbooks.”

Though Gorney was seldom more than one show away from financial disaster, he ran a professional operation, and he had an effective sales technique: He promoted the art to collectors until they came around. “When no one was paying attention to Meyer Vaisman, he was hammering away — ‘His work is important; his work is important,’” says Manuel Gonzalez, director of the art program at Chase Manhattan.

“Some people think he’s a rug merchant,” Cameron admits. “His business manner may be perceived as not quite as blasé as would fit the SoHo mold. When you sit down at the table with Jay, you really have to hang on. But I would venture to say they really don’t know who he is.”

“He’s a total narcissist,” says another friend. “That’s why he’s a great dealer. He sees his artists as an extension of himself. He’s filled up every inch of that gallery — it’s all him. Every person in there is one of his organs, and every picture on the wall is one of his projections. It’s kind of horrible, and it’s kind of wonderful.”

Barbara Bloom, “The Reign of Narcissism” (1988-89)

GORNEY’S NEWEST PROJECTION is Barbara Bloom, a Cal Arts graduate who joined the gallery two years ago. Her first installation there, The Seven Deadly Sins, was arch and theatrical. “We had a private joke matching sins with collectors,” Gorney says. Her second, The Reign of Narcissism, was a maniacal display of ego. The artist’s image assumed every imaginable form: silhouettes, busts, cameos, astrological charts, dental X-rays, tombstones, epitaphs. What some people saw as nasty and revolting, others saw as startlingly provocative.

“What I love about Barbara Bloom is her subtlety,” Gorney says, straight-faced. “Her work creeps up on you. With the first view of it you think, How lovely! Then it becomes sickening and cloying. It’s about the way in which an artist becomes a product. It’s also about mortality, about death, about creating a monument to yourself. And she’s implanted her face on the art world.” He rubs his hands together gleefully. “It’s very audacious.”

Lately, however, all this obsession with mythification and success has begun to look a trifle self-indulgent. Gorney’s best friend from high school has just died of AIDS. A good friend from college is sick. Ironic posturing hardly seems an appropriate response. Even Vaisman is shifting his focus: “The whole theory of commodity art,” he says, “is going to go out the window very quickly.”

Tim Rollins + K.O.S., “Amerika–For Karl” (1989)

“THE IRONY OF THIS PROJECT,” Tim Rollins remarked over breakfast at the Empire Diner, “is that I find it easier to get one of these paintings into the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art than to get one of these kids to apply to art school.”

“There’s kind of a built-in fear of failure,” Gorney ventured.

“Fear of success,” Rollins said. “Because then they’re really in trouble.”

A black livery car pulled up to the curb. We were going from Chelsea, where Rollins has lived for ten years with Kate Pierson of the B-52’s, to the South Bronx, where he and his Kids of Survival have their studio. A round-faced 35-year-old, Rollins grew up in the working-class town of Pittsfield, Maine. When he got to New York, he headed straight for the Chelsea Hotel, half expecting to find Warhol filming Nico and Ondine. “I always wanted to be an artist as a kid,” he said as we headed for the Willis Avenue bridge. “My mother’s thrilled that I’m making a living at it.”

“Meyer Vaisman still sends his mom and dad all his reviews,” Gorney remarked.

Rollins was teaching art at I.S. 52 in the South Bronx when Gorney exhibited some work from the Kids’ Amerika series—gold paint on pages from the Kafka novel mounted on linen. Other dealers had included them in group shows, but only Gorney offered to take them on. The first show got no response from collectors, but after it came down he made a sale to Saatchi—the jackpot. Rollins was at a parent-teacher conference in the South Bronx when he got the news.

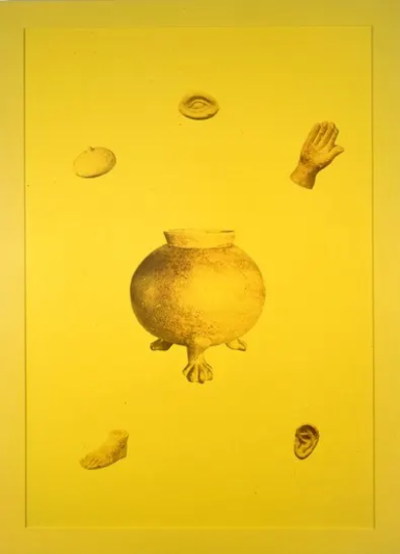

Tim Rollins + K.O.S., “The Temptation of Saint Anthony XXXVI – The Sun” (1990)

The studio is in a massive industrial building on a narrow, curving street. At night, there are hookers outside; in the morning, vandalized cars. Inside, between the roar of jets taking off from La Guardia, parakeets could be heard chirping in their cage. “We like the atmosphere it gives,” said one of the Kids.

Gorney was there to pick out some single-page studies from the series they were doing for a show at the Kunstmuseum in Basel—paintings in blood on pages from Flaubert’s The Temptation of St. Antony. The youngsters first used blood three years ago, in Journal of the Plague Year, when they painted “abracadabra” (a mystical chant once thought to ward off the plague) on the Defoe novel so the letters seemed to extend into infinity. Now they were finishing the centerpiece for the Basel show, a triptych depicting the Trinity.

In the center panel, a wide circle recalled the passage where St. Antony looks skyward and sees Christ’s face in the sun. On the left, God the Father was represented by a pair of bloody splats that dribbled toward the floor. On the right, the Holy Spirit covered the entire panel, diffuse, omnipresent.

The Holy Spirit needed another coat. George Garces, a seventeen-year-old from Washington Heights, poured a quart or so of defibrinated beef blood from its plastic container into a small bucket. The air was suddenly thick with it. As Gorney, about to leave, extended his hand, Garces started to pull off his rubber glove. “Always wear a condom,” Gorney said. “It’s the thing to do.”

“THE SEMIOTICS OF ODEON are very interesting,” Gorney mused as his crowd of diners settled at their tables after the Peter Nagy opening. “It’s very late seventies, you know.” Before Odeon and Mary Boone and the neo-Expressionists, artists hung out in bars like the Locale, a basement joint near Wahington Square. Then they started wearing Armani suits and ordering $70 dinners.

JACKPOT

Gorney managed to sell one of Rollins and the Kids’ works to Charles Saatchi.

June 25, 1990

June 25, 1990