Excerpted from Real Men: Sex and Style in an Uncertain Age, a book about what it means to be a man in America. Text by Frank Rose, photographs by George Bennett; published by Doubleday/Dolphin in 1980.

Photographs by George Bennett

“DEE DEE’S SO LOVABLE! Dee Dee can get away with murder. Dee Dee can be the culprit and you say, ‘Awwww, it’s Dee Dee.’ He’s the sweetheart of the Ramones. What can I say? He’s Dee Dee!”

I was sitting in the midtown Manhattan offices of Coconut Entertainment, the management company set up by Danny Fields and Linda Stein, listening to Linda on one of her favorite clients. It was the summer of 1978, a time of transition for the band that invented punk rock, for the music industry as a whole. A trade magazine on the table carried articles hailing the advent of “creative sterility” in the business. Linda turned to ask Danny what he thought made Dee Dee so distinctive. “His IQ,” Danny said, in his laconic way. “His abiding sense of decency, justice, honor, integrity, morality. . . . He’ll also sleep with anything, which makes him very hot.”

Linda giggled. “He’s definitely the sexiest Ramone, isn’t he? The most available. We could be in London, for example, and if I say I’m going to see Elton, Dee Dee will be the first one to jump up and say, ‘I wanna go!’ The others are just not interested. John is very satisfied to stay home and watch a great film, and Joey’s idea of going out on the town is—well. Dee Dee just likes to party more than the others do. And Dee Dee has the most girlfriends. People just fall in love with Dee Dee.”

People do fall in love with Dee Dee—with his mischievous grin, his big brown eyes, his bashful, awkward voice, even his volatile temper. Naturally, Dee Dee is not unaware of his appeal. “I’ve always been very loved,” he’d told me earlier, “and I’ve always rejected it. I’ve always felt too worthless to accept that kind of intimacy from anybody—relatives, girls, teachers, anybody. When you’re leading a life of crime, and you’re just doing that because you want to be destructive, you’re not going to be happy with yourself. What I should have done was build some kind of foundation, but I didn’t. I turned the opposite way. Something was tormenting me. Emotionally I went through hell, until I found myself.”

People do fall in love with Dee Dee—with his mischievous grin, his big brown eyes, his bashful, awkward voice, even his volatile temper. Naturally, Dee Dee is not unaware of his appeal. “I’ve always been very loved,” he’d told me earlier, “and I’ve always rejected it. I’ve always felt too worthless to accept that kind of intimacy from anybody—relatives, girls, teachers, anybody. When you’re leading a life of crime, and you’re just doing that because you want to be destructive, you’re not going to be happy with yourself. What I should have done was build some kind of foundation, but I didn’t. I turned the opposite way. Something was tormenting me. Emotionally I went through hell, until I found myself.”

DEE DEE WAS A COLD WAR BABY. He was born Douglas Colvin at Fort Lee, Virginia, in September 1952. His father was an Army noncom who worked for the Criminal Investigation Division and was stationed most of the time in Germany until the mid-sixties. His mother is Prussian, from a wealthy industrialist family that was ruined by the Nazis. They met in Berlin after the war; she was a dancer then, at the Scala.

Before and After Punk |

A mild-mannered music reporter goes to this dive bar on the Bowery . . . |

Why Elvis?The King was just a sweet mama’s boy whose vague dreams of stardom took him places he’d never dreamed of.

|

Minimal and MysticalWhat does “Einstein on the Beach” have to say to us in this post-Minimal era?

|

Laurie Anderson, Multimedia Techno-WaifA spiky-haired extra-terrestrial stumbles forward into the future.

|

A Rotten Success StoryPublic Image Ltd.: Are they committing rock’n’roll suicide, or are they simply boring?

|

Welcome to the Modern WorldScavenging through the artifacts of the Fifties and the attitudes of the Sixties are the brave new children of today. Like the beats and the hippies before them, they have something to tell you.

|

Dee Dee Ramone Didn’t Wanna Be a Pinhead No MoreSo the New York rocker who practically invented punk kicked heroin, bought a dinette set, and married Vera, who was, you know . . . normal.

|

Discophobia!Rock & roll fights back.

|

Peter Townshend Gets Old Before He DiesThe leader of the Who has been questioning his role in the youth cult for most of this decade.

|

Elvis Costello Wins Friends and Influences PeopleLast Friday afternoon, the avenger had some explaining to do.

|

Danny Fields Is a Number-One Fan“When I first saw the Ramones I went up to them after the set and—‘You guys are great! You guys are great!’ That’s all I could say.”

|

Four Conversations with Brian EnoHe can look into an interviewer’s face and measure the determination to report something weird.

|

The Butch Fantasy: America Goes PunkCBGB or the Eagle? Both bars traffic in mythic projections of masculinity. But as someone who’s hung out in each, I’ve been known to get confused. And why not? It’s a natural response to being dropped into mirror worlds.

|

Berlin was what Dee Dee knew as home. He grew up in a well-kept neighborhood that was sort of a showplace for American military personnel. Tanks rolled down the street on maneuvers every afternoon at five o’clock; the Wall was a short bike ride away. He liked to play in the bombed-out bunkers, but whenever he came home with Nazi relics, his parents always got livid and ordered him to throw them away. He never quite understood why.

When Dee Dee was fourteen, his parents split up. He moved to Queens with his mother and younger sister the same year. His father didn’t write to him much after that, and when he did, Dee Dee never bothered to answer. Dee Dee had trouble adjusting to America—especially to the American educational system. In Germany, he’d gone to military school; the discipline was tough, but at least he’d learned something. Here it was absurd. He walked in his first day at Forest Hills High School and he couldn’t even understand what registration was. The teachers seemed to be asking him to plan his entire future in ten minutes.

He didn’t have time to think. He asked for shop, but they told him he had to get an academic diploma. He said he only wanted the easiest courses. They spent more time trying to control their kids than teaching them. The teachers put kids in study hall and watched to make sure they didn’t move. After a while, Dee Dee just started sneaking out. He’d crawl back into bed for a couple of hours’ sleep, then go hang out with a bunch of other kids, drinking beer in a park just off Queens Boulevard or sniffing glue at somebody’s house.

At fifteen, he got a job in a supermarket. He was stamping prices with a bunch of guys in the basement one day when they asked him if he wanted to snort smack. He didn’t know what smack was, but everybody was laughing at him, so he figured he’d better do it. It just made him nauseous. But those guys made such a big deal about it, he thought it had to be special, so he tried it again. Within a month, he was shooting it. When he found out it was heroin, he really felt cool.

When he turned sixteen, Dee Dee got his mother to sign him out of school. After that, Dee Dee worked at a whole series of jobs, but none of them seemed to work out. He got a job as a butcher’s apprentice, but a steer fell off its hook and nearly killed him. He got a job in an electronics store selling stereos he didn’t know how to work. He worked as a mail clerk and in an ad agency in Manhattan. Once he even borrowed somebody’s portfolio and conned himself into a job doing paste-ups at an art studio. He got a lot of breaks, but it seemed like he screwed them all up. And he never felt there was anyone around to give him any real direction. Even after he’d busted his tail and earned his equivalency diploma and needed to know how to get into college, his father never bothered to explain.

It was okay. Adults had their own problems, and Dee Dee was in no hurry to grow up. He and his friends were outcasts. They weren’t like the other kids, all so predictable. Those kids would play wild for a little while, then give it up the first chance they got to take their place on the assembly line. Dee Dee was willing to take a chance on a longer childhood.

Didn’t he think about his future?

“I worried about it,” he said. “I knew I never wanted to go into crime to make money. I just always hoped I’d be a rock star, I guess. What else can you think about?”

THE ORIGINAL RAMONES—the drummer has since withdrawn and been replaced—were four punks from Forest Hills, Queens, who reinvented rock ’n’ roll while living in the back of a paint store. They did not, of course, set out to reinvent rock ’n’ roll. They set out to play it, but they encountered two problems right away. One was that they’d all reached their late teens without learning an instrument. The other was that they all had extremely bad attitudes. (Once Dee Dee and Joey, the singer, went to audition for some kids on Long Island who wanted to get a group together and who had taken out a classified ad in Rolling Stone. Asked if they could play “Gimme Shelter,” they said sure, pulled out a conga and a guitar, and started making random noise.) These handicaps prevented Dee Dee, Joey, Johnny, and Tommy—that’s what they called themselves—from developing in the normal way. Because they knew only a couple of chords, they were able to produce only the most rudimentary sounds. Because they were hostile and adolescent and too smart for their own good, they let it come out like a barrage of white hate. The result eventually became known as punk rock, but at the time it was just a last-ditch maneuver on the part of four screw-ups who didn’t want to spend the rest of their lives sorting mail.

Dee Dee, Joey, and Johnny were the nucleus of the Ramones. They’d been hanging out together since Dee Dee was fifteen. Johnny had already left school when Dee Dee met him, and Joey—well, Dee Dee doesn’t think it was even possible for Joey to go to school. All three of them had the capacity to cause trouble simply by walking down the street, and all three of them talked about being in a rock band every day. But talk was all they could do; everybody they knew who was actually in a band had been playing since sixth or seventh grade.

Tommy appears to have been the catalyst of the group. He was a couple of years older and ran with a crowd that was serious about music. He told them they ought to be a band because they looked good together. He took them to Manhattan, to places like Nobody’s on Bleecker Street, and Max’s Kansas City, where David Bowie and Mick Jagger and Lou Reed hung out in the back room. That was in the early Seventies, when the glitter look was in. People tramped about on three-inch platform shoes and wore skintight satin pants and frilly, open-chested shirts with sequins all over them. Everybody had either a shag hairdo or a multicolored Afro, sometimes with Christmas-tree lights inside. Dee Dee and Joey and Johnny were embarrassed because all they had to wear was dirty blue jeans and old T-shirts; they looked like punk kids. Then they bought snakeskin boots and had their hair done.

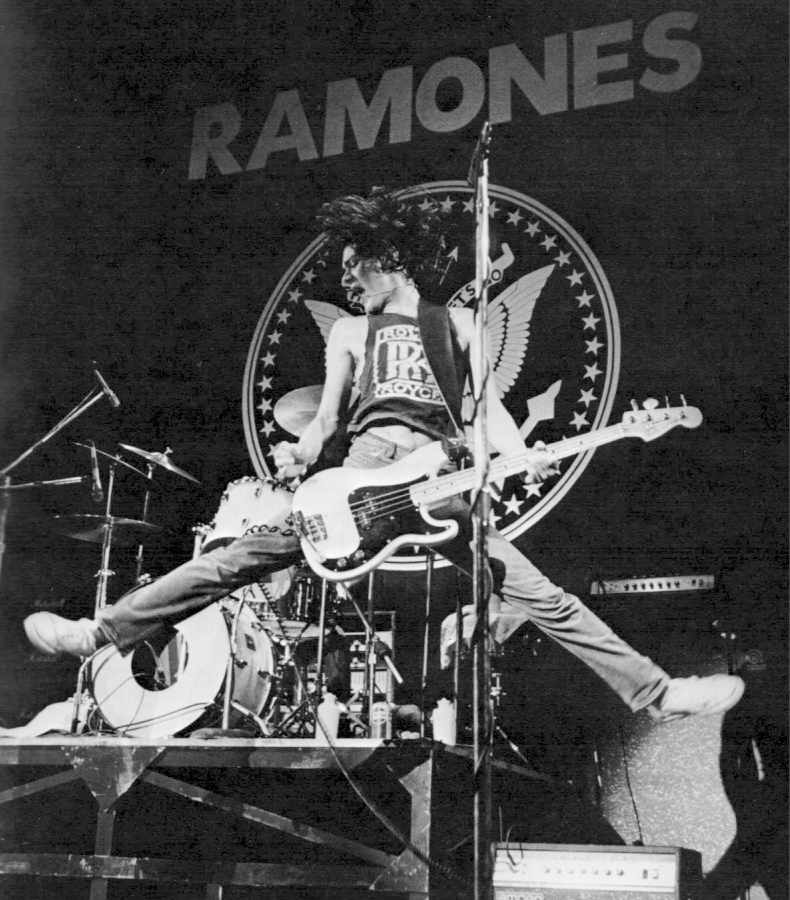

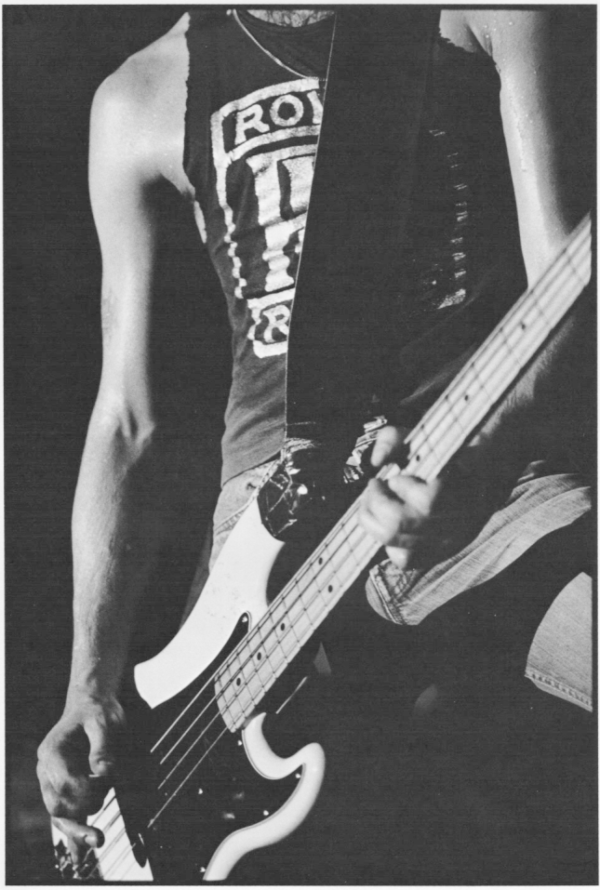

HE HOLDS BACK NOTHING

The Ramones believe in storming the stage and mowing down the audience with numbers like “Teenage Lobotomy” and “Gimme Gimme Shock Treatment.”

Like everybody else who was into glitter, they spent a lot of time listening to the New York Dolls. Unfortunate marketing strategies and other factors conspired to keep the Dolls from ever becoming a national phenomenon, but as far as New York was concerned, they were the most exciting thing since 1966, when Andy Warhol had introduced the Velvet Underground. Musically, the Dolls were hard and loud and crudely reminiscent of the early Rolling Stones; stancewise, they were street tough but femme. What really impressed Dee Dee and Joey and Johnny about them, however, was their ability to get onstage and express themselves without $20,000 worth of equipment.

After seeing what the Dolls could do, Dee Dee and Johnny bought fifty-dollar guitars and tiny little amps and started practicing about two hours a week. The rest of the time Johnny was working construction and Joey wasn’t doing much of anything; but Dee Dee was studying cosmetology at night school while shampooing the heads of middle-aged matrons by day at Bergdorf Goodman, where he’d gotten a job as apprentice hairdresser. (It was another of his attempts to locate a career; he hated it.) After Joey’s parents kicked him out of the house, he and Dee Dee started sleeping in the back of a paint store. When it got cold, they found girl friends with apartments and moved in. Every spare cent they had went to buy records—rockabilly, Fifties rock ’n’ roll, anything from England. They didn’t like what was on the radio. They wanted songs, not guitar solos.

Tommy, the drummer, didn’t join them until the end of 1974. After that, everything started to click. They picked their name after Dee Dee read that Paul McCartney used to call himself Paul Ramone during the Silver Beetles tour. Dee Dee and Joey and Johnny started writing songs. They started rehearsing in earnest. Then they discovered a little dive on the Bowery called CBGB.

CBGB stands at the foot of Bleecker Street, its bright lights and dirty white awning illuminating a real-life stage set of urban depravity. Derelicts carrying oily rags stagger into nearby intersections, hoping to wipe someone’s windshield for a quarter. Others lie sprawled unconscious on the sidewalk under greasy scraps of blanket. Crumbling tenements and weed-choked, rubble-filled lots create a sinister streetscape suggestive of postwar Berlin as it looked with Marlene Dietrich in A Foreign Affair.

CBGB is a dank, narrow, tunnel-like room with neon beer signs overhead and a tiny stage at the end. There aren’t any dressing rooms at all. But when the Ramones found the place, nestled in among the gas stations and fleabag hotels and auto junkyards and off-off-Broadway theaters and soup kitchens, it was just what any fledgling rock ’n’ roll band would die for: a place to play, not Beatles and Led Zeppelin songs, but stuff that was original.

By this time the snakeskin boots and mod hairdos were gone; the Ramones had reverted to ripped blue jeans, dirty T-shirts, worn-out sneakers. And when they got onstage, they didn’t feel like laying back. They put on shows that were, in Hobbes’s phrase, nasty, brutish, and short: twenty minutes on the average, with song titles like “Beat on the Brat,” “Blitzkrieg Bop,” “Now I Wanna Sniff Some Glue,” and “I Don’t Wanna Walk Around with You.” It was simple assault: They mounted the stage, mowed you down, and were gone before you even had a chance to think about it. Nobody had ever done it like that before. They were a hit.

Less than a year after they arrived, CBGB staged a three-week festival of new bands, The Village Voice proclaimed the emergence of a “new rock underground,” and the scene was officially on. CBGB had begun to fill up. Manager Hilly Kristal’s open booking policy had drawn bands from all over the area, and they were beginning to draw fans. Groupies and journalists followed. Record company people held out longer, but eventually they started coming around as well. Suddenly there were not just cabs outside on the Bowery, there were limousines.

In January 1976, after circulating a crudely recorded demo tape and performing at several private auditions, the Ramones became the first of many CBGB bands to land a record contract. They immediately went into a recording studio and cut an album of fourteen songs, all less than three minutes in length, at a widely reported cost of $6,400, which is about what most groups required to do the guitar tracks. The record was called Ramones; its front cover pictured the group in ripped jeans and black leather jackets, standing in front of a graffiti-scarred wall. It got a lot of press, but with lines like “I’m a Nazi schätze/Y’know I fight for the fatherland,” it was not designed for maximum airplay. Records that don’t get airplay don’t sell big; but at a cost of $6,400, that wasn’t so terrible. And on the Bowery, at least, the Ramones were superstars.

Of the dozens of bands that regularly played CBGB, only they and a couple of others were widely acclaimed as original and important. (“Originality,” Tommy told me at the time, “is hard to find.”) Their detractors claimed they knew only three chords, but that didn’t matter because they were indisputably the right three chords. (“I dunno who said it,” he added, “but less is more.”) In fact, although the CBGB bands were a highly mixed lot, it was the Ramones whose style defined the scene. That style failed to connect outside New York City until July 4 and 5, 1976, when the Ramones played their first historic gigs in London. But the result of those two dates, according to their then managers, Danny Fields and Linda Stein, and to Seymour Stein, who runs their record company, was the birth of punk rock—a Bicentennial gift from the Ramones to Great Britain, arriving just in time to inspire British youth to articulate a suitable response to the Silver Jubilee: Johnny Rotten’s snarling version of “God Save the Queen.”

BEING NORMAL IS TOUGH

It didn’t matter that Dee Dee was a loser, a high school dropout, a no-talent troublemaker with a taste for hard drugs — he still became famous. But did it make him happy? Did it make him proud? No.

As punk became a fad, many bands unfortunately failed to heed one of the Ramones’ basic points, which was that an inability to play should produce not poor musicianship but an extreme economy of style. But the hostility—the teen meanness born of boredom and frustration that had led them to drop TV sets from rooftops onto passersby in Forest Hills—that was a message nobody could miss. They packed a wallop into their two-minute nuggets of sound that was awesome to experience.

But those early songs were not merely violent. The Ramones had a passion for punishment. Their music became a vehicle for inflicting it on themselves and on others. They were errant, and they knew it, and since nobody else seemed to care, they had no choice but to take up the cudgel themselves.

“I was very delinquent,” Dee Dee admitted. “I think I was tormented somehow. I robbed people and stuff, I used to take drugs all day long, and I’d hate myself for that, and then I’d just get in more trouble. I was just shiftless. I never had a father to control me. There was nobody there to control me, so I just ran loose.”

DEE DEE TOOK HEROIN FOR TEN YEARS—from 1967, when he was fifteen, to 1977, when the Ramones recorded their third album, Rocket to Russia. At first he copped in Central Park, buying, say, fifteen $2 bags for $24, keeping three for himself, and selling the rest to other kids in Queens for $4 apiece. But when the French heroin disappeared and the brown Mexican cut with procaine took its place, he started going downtown. The Mexican yielded a weird high, changing laid-back addicts to violent, hopped-up ones; there was no way to get satisfied. He’d cop at places like Avenue D and Ninth Street on the Lower East Side, and since that wasn’t easy to do—especially if you were white—he found a lot of people who would give him $200 or so and let him keep half of what he bought. When that wasn’t enough or when his girl friend of the moment wouldn’t give him money, there were other options. He didn’t go in for burglary; he didn’t like the idea of going into dark, empty apartments all by himself or of running down fire escapes with TV sets on his head. Stickups, on the other hand, were not so bad. His victims were other junkies; he carried a nine-millimeter Walther P-38 automatic for credibility.

Dee Dee tried methadone detoxification about sixteen times but always with unhappy results. Each time he was put on a twelve-day program, given no counseling, and started on a forty-milligram dose, which was stronger than what he was used to at first. After twelve days he usually wound up more strung out than before. His first couple of attempts were sincere, but after that he began to use the detox program as a safe way of staying high if he couldn’t hassle getting the money up to cop. Still, he scorned methadone maintenance. “The maintenance program is for vegetables,” he said. “And I never wanted to be a vegetable.”

As the Ramones became more successful, Dee Dee simply couldn’t afford to be a vegetable. At one time, when he was having trouble taking care of himself on tour, he thought the other three Ramones wanted him to leave the group. They never said anything, though; they left him alone to come to terms with himself. He still isn’t sure how he stopped. He likens it to a miracle, or an exorcism.

THE DEATH OF PUNK

As far as the Ramones are concerned, the trend they helped spawn is dead. It’s time to move on, time to reach out, maybe even time to record a few ballads. But retire and get a job? Are you kidding?

Linda thinks part of it was the Ramones themselves, who had come to take the idea of rock stardom very seriously. “They wanted to succeed,” she said. “They wanted to sell records and tickets and make money. So they became very demanding. You can’t ever be five minutes late, you can’t ever not come to rehearsal, you can’t ever make a mistake onstage. I don’t care if the audience is howling for encores, if you made a mistake, when you get off that stage you’re being screamed at by the other Ramones. As long as you’re a Ramone, there’s no room to misbehave or get yourself screwed up. I think that’s the secret of Dee Dee’s being straightened out. I mean, it’s like a Nazi army!”

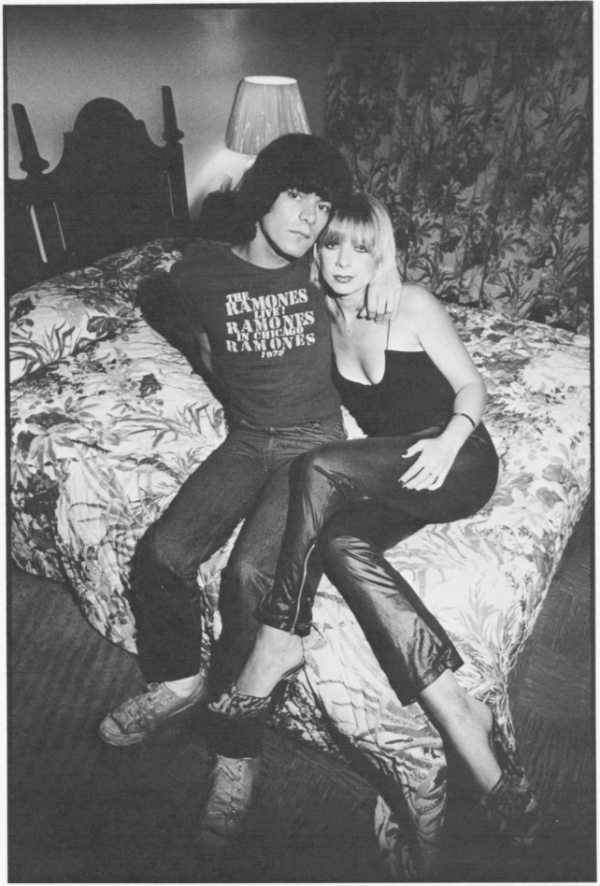

Equally important, however, has been the influence of Vera Ramone. Dee Dee and Vera had met at Max’s Kansas City: She was standing at the bar, and he went up and told her who he was. She thought he was egotistical but kind of cute; to him, it was like love at first sight. The following May they were engaged, and in June, after several months of camping out in Danny’s loft, they moved into a basement apartment in Queens, not far from where her parents live. They married in September 1978, one day before the Ramones were scheduled to embark on a month-long tour of Britain and the Continent.

Vera was working part-time as a hairdresser in Brooklyn. She has the peroxide-blonde look of a lot of girls one would meet at Max’s, except that she smiles a lot and her eyes aren’t dull. Everyone seems to like her and to agree that she’s good for Dee Dee. (“Vera’s like great,” said Joey. “She’s not a nut.”) Still, the idea of marriage caught many by surprise, as did the idea of moving to Queens—especially since Dee Dee has always been viewed as the fun-loving Ramone most likely to lead the life of rock royalty.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Linda said. “Danny and I always thought Dee Dee should have an affair with Farrah Fawcett or somebody very famous. He could be like Cher and just keep having affairs with famous people. But he chose to be completely domesticated and settle down in Queens—with all his cutlery and all his porcelain and his dinette set and his living room sofa and his color TV. We wanted to buy him a very practical gift, but he already has everything. They’re having this real wedding, they have this real dinette set, they’re having everything except the honeymoon—because he’s leaving the next morning for Helsinki.”

THE LAST TIME I SAW THE RAMONES perform was at Hurrah, a sort of uptown punk disco around the comer from Lincoln Center. It was August, a couple of weeks before the wedding. Hurrah’s air conditioning was broken; the tiny dressing room was hot, damp, airless, and unbearable. The crowd outside was getting impatient. A chant of “Hey, ho, let’s go!” went up—that’s the opener to “Blitzkrieg Bop,” the Ramones’ first single—but the band refused to budge from their dressing room until half past midnight. They never leave until they’re ready. They have to psych themselves for every performance. They have to focus their thoughts. They have to be able to intimidate people.

Finally, as beer spray arced over the crowd and fists shook in the air, the Ramones stormed the stage, took their positions, and delivered a backbeat that began with a roar and could have filled a horizon. “We’re the Ramones,” yelled Joey, “and this one’s called ‘Rockaway Beach’!” The intensity of their attack was broken only once, when Dee Dee destroyed two instruments in quick succession. Otherwise they mowed without interruption through an hour-long set that included “Teenage Lobotomy,” “Gimme Gimme Shock Treatment,” “Pinhead,” “I Don’t Care,” and “I Don’t Want You.” After the second encore, Joey started stumbling and had to be helped down the hall to their dressing room. Snot was dribbling from his nose.

This show was somewhat unusual in that it was a benefit for their managers. Danny, a sort of underground taste maker who’s been involved with some of rock’s most historic fringe (he managed Iggy and the Stooges until they drove a fourteen-foot truck into a bridge with a twelve-foot clearance, drawing three lawsuits as a result), had started managing the Ramones full-time in the fall of 1975. At the beginning of 1978, he went into partnership with Linda, who’d been working with the group in the international department of her husband’s record company. The economics of the music business are such that a band never gets out of hock and begins to make money until it makes a lot; in the meantime it lives, tours, and records on record company advances. The Ramones signed with Sire Records, a small label then distributed by ABC, for a minuscule advance, and while they’ve never owed a tremendous sum, they’ve never made much either. They paid themselves four-figure salaries (excluding royalties, which were split up among the band, their agent, and their managers), and Danny and Linda waived their share when a new amp or a new leather jacket was needed. Before long, however, the situation changed.

The establishment of Coconut Entertainment as a fulltime enterprise was one of several steps in the transformation of the Ramones from rock dream to legitimate business venture. Other steps, all taken in 1977 and 1978, included the signing of a distribution pact between Sire and Warner Bros. Records, one of the two biggest distributors in the country; the signing of the Ramones with Premier Talent, America’s number one booking agent; and the hiring of an accountant to tell everyone in the band how much money they have. Yet another step was the recording of Road to Ruin. It was their fourth album, but as its release date neared, Seymour Stein was confidently predicting that most people would think of it as their first.

DEE DEE’S NORMAL LIFE

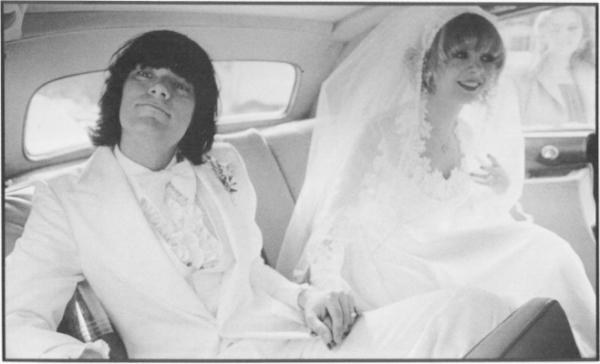

What Dee Dee wanted was to be normal. What he found was Vera. What he did was march down the aisle with her to the tune of “Ave Maria,” a sweet little song that just never made it on AM radio.

Road to Ruin presented a different Ramones—more melodic, not above an occasional ballad, ready to build on the stripped-down musical structures Danny calls “primitive evolved” and likens to ancient Egyptian pottery and Andy Warhol’s eight-hour film of the Empire State Building. In fact, they were finally learning how to play. They had also decided to make an album that would get AOR airplay. AOR—that’s Album-Oriented Rock, the basic late-Seventies FM rock format—is what the Ramones need to break nationally, and like all formats, it has certain standards. One is that songs should not be characterized by overwhelming hostility or repeated references to glue sniffing. Thus Road to Ruin contained two cuts, one upbeat, the other innocuous, that were marked for immediate release as singles in different markets and a third that was expected to establish them firmly as AOR artists. That song was “Questioningly,” a ballad by Dee Dee. As far as the Ramones were concerned, it could have been the first ballad ever recorded.

The Ramones had conflicting feelings about the new record. Joey and Dee Dee liked it; Johnny was having trouble believing it was the Ramones. When Linda told Ed Rosenblatt, Warner’s senior vice-president in charge of sales and promotion, that the Ramones felt a little like they’d sold out, he said she should tell them to think of it as reaching out. Of course, only the Ramones could record one song about a kid who’d killed his entire family and turned into a vegetable and another song called “I Wanna Be Sedated” and still worry about selling out.

Still, it was 1978 and time to carve out some sort of post-punk identity. The movement the Ramones had helped spawn had mushroomed into the kind of media myth hip college students write theses about. “I think punk’s like seen its time, you know,” Joey said. “It’s kind of a lot of crap, you know.” Said Dee Dee, “It’s over. It’s finished. And whatever it wanted to prove, it proved. I think it showed that self-destruction and chaos are fine to shake something up but not fine to use as a pattern to live your life by. Otherwise you just end up with nothing, and so does everybody else.”

WHEN DEE DEE AND VERA moved to Queens, it was to a modest, quiet neighborhood of one-, two-, and three-family homes, a remote part of the city with well-kept yards, pleasant trees, and children who never play in the streets. Two days before the wedding, I visited Dee Dee and Vera in their new home. It’s a nice-size apartment with a living room, kitchen, dining alcove, and two bedrooms, one furnished in a Mediterranean-style bedroom suite with matching green-and-white bedspread and drapes, the other filled with Dee Dee’s collections of records and Weird War Tales comics. The living room furniture hadn’t been delivered yet, so we sat at the glass-topped table, which Vera said they’d only gotten by a miracle because somebody had found it in the warehouse.

WHEN DEE DEE AND VERA moved to Queens, it was to a modest, quiet neighborhood of one-, two-, and three-family homes, a remote part of the city with well-kept yards, pleasant trees, and children who never play in the streets. Two days before the wedding, I visited Dee Dee and Vera in their new home. It’s a nice-size apartment with a living room, kitchen, dining alcove, and two bedrooms, one furnished in a Mediterranean-style bedroom suite with matching green-and-white bedspread and drapes, the other filled with Dee Dee’s collections of records and Weird War Tales comics. The living room furniture hadn’t been delivered yet, so we sat at the glass-topped table, which Vera said they’d only gotten by a miracle because somebody had found it in the warehouse.

Dee Dee was suffering from a recurrence of hepatitis; for a while there’d been talk of canceling the tour, but he wasn’t all that sick, and anyway, Johnny would have killed him. Everybody was all excited about the upcoming weekend. Vera’s gown, floor-length and white with a full veil, had just arrived from California the day before, and Dee Dee had spent the whole afternoon looking for a new black leather jacket to replace the last one, which had been stolen out of the group’s van. They don’t make leather jackets like they used to, so he’d spent the whole evening putting the studs on himself. “I can’t wait till our furniture comes,” he said.

Dee Dee was happy about moving back to Queens. “It’s more normal,” he said. “I lived too bad for too long. I wanna start trying to live nice.” He also liked the idea of getting married. “I think it’s better if you want to have children,” he said.

“It really seemed like the right thing to do,” Vera put in.

“It’s not something we were pressured into doing,” Dee Dee added. “In fact, the priest almost tries to talk you out of it. And I’m not getting any younger either.”

“None of us are,” Vera said.

I asked Dee Dee about stardom and the band’s plans for the future.

“The way things are going now,” he said, “I plan to stick with it for a long time. I plan to keep going. What else are we gonna do? I have no skills. I couldn’t get a job doing anything else now. And I like it. Plus, the work is less severe the bigger you get. You don’t have to tour two hundred fifty days a year.

“But I’m not a greedy person or anything. If I ever have like millions of dollars—which I think I’m going to, probably I’ll look fifty, but at least I’ll have it—I don’t know what I’ll do with it, probably just buy a house and try and relax. There’s plenty of things I like to do. I like to go hunting and stuff and be able to do normal things like everybody else. But of course, there’ll always be a mean streak in me. I can’t help that, you know.”

I mentioned that he seemed concerned with the idea of being normal.

“Yeah,” he said, suddenly tensing. “I wanna be normal really bad. I don’t wanna be crazy. . . .” His knuckles were growing white.

Vera looked over from the sink. “What are you doing to the table, Dee Dee?”

“I’m sick of being crazy.” He didn’t seem to hear her. “It’s been crazy all my life. I guess I have my crazy moments. But I have so many good friends, I have a very good life. . . .”

“He’s loved, you know,” Vera interjected. “Everybody loves him.”

“Like I’m just a really happy guy, that’s all.” Dee Dee laughed. Children were playing outside. Their shrieks came down through the open window and filled the room.

THE WEDDING WAS HELD at Saint John Nepomucene Church on the Upper East Side of Manhattan; that was where Vera’s parents had married and where Vera herself had been baptized. Only about fifty people were invited, most of them relatives. Johnny didn’t make it, but Joey and Tommy did, and Danny, Linda, and Seymour. Afterward there was a reception at a restaurant in Queens with music by a rock band whose repertoire includes the Beatles, some disco, and a lot of wedding songs. Dee Dee had suggested they hire the Dead Boys, but he only meant it as a joke.

Dee Dee arrived at the church in a black Cadillac limousine. He was wearing a custom-tailored white tuxedo with frothy white shirt and white shoes. He said he’d gotten so panicky getting dressed like that, he’d had to take out his old Ramones scrapbooks and look at them. Vera arrived with her parents in a white Rolls Royce. It was quite a nice wedding, with bridesmaids in acres of chiffon and a soloist high in the balcony who sang “Ave Maria” and “The Lord’s Prayer”; just like thousands of others all across America that day, except that the priest interrupted the ceremony to speak extemporaneously and at length on the sanctity of the marriage vows and the importance of marital fidelity. But he married them all the same, and Linda sobbed as they got into the Rolls for the trip back to Queens.

A YEAR AND A HALF AFTER THE WEDDING, Vera and Dee Dee and the rest of the Ramones were off to Europe again—this time to England, touring to support yet another new album. End of the Century it’s called, and there are no leather jackets on the cover of this one, just four guys in the kind of T-shirts you find at Bloomingdale’s. (Dee Dee’s is black.) It all fits in with the new image. The Ramones are film stars now, having made their acting debut in the Roger Corman grade-B epic Rock ’n Roll High School, about “the school where the students rule.”

Rock ’n Roll High School draws the faithful to midnight shows in Manhattan, but it’s also brought in a whole new audience of twelve- and fourteen-year-olds in Dayton and Kansas City and places like that—boppers in the heartland. The Ramones will be on the road in America all spring, selling the tickets they need to sell more albums to get more airplay to sell more tickets and albums to people who’ve never heard them before. Rock life is like that. Meanwhile, back in New York, the punk movement they spawned has turned into New Wave and safety pins have given way to skinny ties and the guys in the industry have discovered you can make a lot of money from albums that only cost $6,400 or so to record, provided you know how to market them right. Dee Dee still hasn’t made millions of dollars or anything, needless to say, but then he doesn’t look fifty yet either. ♦

April 1, 1980

April 1, 1980