THE THINKING WENT SOMETHING LIKE THIS: Chevrolet is all about being revolutionary, right? (That’s debatable, but since Chevy’s tagline is “An American Revolution!” this is where all discussion starts at its ad agency.) And if Chevrolet is revolutionary, then its advertising ought to be, too. Ergo, the Chevy message needed to escape the tightly controlled, painstakingly monitored, woefully predictable confines of the 30-second TV spot and roam the online jungle. But everybody’s doing that now. So, Chevy marketers thought, let’s take this thing a notch further — let’s have an online contest to see who can create the best TV ad for the new Tahoe. The wikification of the 30-second spot — what could be more revolutionary than that?

Almost nothing, as it turned out. Last spring’s campaign for the Chevy Tahoe broke every rule of marketing. The MBAs who populate ad agencies and corporate marketing departments spend years learning the art of control — what their cleverly calibrated messages should (and shouldn’t) say, where they should appear, how often they should appear there, and what should appear nearby. Chevy decided to chuck all that and invite people to post their own commercial messages about America’s best-selling SUV online, where the ads would be free to migrate to YouTube or anywhere else. Chevy supplied the video clips and music; users could then mix and match the material and add their own captions.

Almost nothing, as it turned out. Last spring’s campaign for the Chevy Tahoe broke every rule of marketing. The MBAs who populate ad agencies and corporate marketing departments spend years learning the art of control — what their cleverly calibrated messages should (and shouldn’t) say, where they should appear, how often they should appear there, and what should appear nearby. Chevy decided to chuck all that and invite people to post their own commercial messages about America’s best-selling SUV online, where the ads would be free to migrate to YouTube or anywhere else. Chevy supplied the video clips and music; users could then mix and match the material and add their own captions.

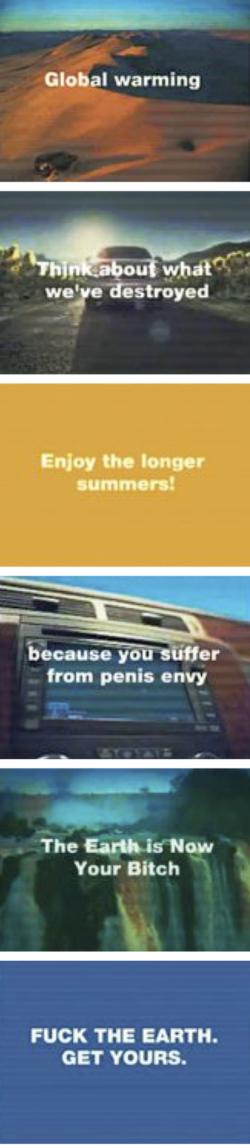

The contest ran for four weeks and drew more than 30,000 entries, the vast majority of which faithfully touted the vehicle’s many selling points — its fully retractable seats, its power-lift gates, its relative fuel economy. But then there were the rogue entries, the ones that subverted the Tahoe message with references to global warming, social irresponsibility, war in Iraq, and the psychosexual connotations of extremely large cars. One contestant, a 27-year-old Web strategist from Washington, DC, posted an offering called “Enjoy the Longer Summers!” which blamed the Tahoe for heat-trapping gasses and melting polar ice caps. An entry called “How Big Is Yours” declared, “Ours is really big! Watch us fuck America with it.” The same contestant (hey, no rules against multiple entries, right?) created an ad that asked the timeless question, “What Would Jesus Drive?” On its own Web site, the Tahoe now stood accused of everything but running down the Pillsbury Doughboy.

Anyone could see how Chevy got here.

TV advertising has been losing its impact for years: McKinsey projects that by 2010 it will be barely one-third as effective as it was in 1990, thanks to rising costs, falling viewership, ever-proliferating ad clutter, and viewers’ TiVo-fueled power to zip through commercials. Big national advertisers like General Motors, which has an annual TV ad budget of $2.9 billion — only Procter & Gamble’s is bigger — are demanding something different, and the rise of Web video offers just that. Internet advertising of any sort promises powers that marketers have long lusted after: the ability to target people who might actually be interested in what they’re selling and to engage those people in conversation. Web video can be as emotionally involving as TV, and when used in consumer-generated campaigns, as crowdsourcing efforts like Chevy’s have come to be known, online clips come with a bonus — people see them less as advertising than as peer recommendation, which countless studies have shown to be far more influential.

But as the Tahoe example demonstrates, all this comes at a price. Users, not marketers, control the dialog online, and never more so than when they’re invited to contribute their own thoughts. For Chevy, and for Madison Avenue, it led to a moment of truth. With attack ads piling up on its site, spilling over onto YouTube, and spinning out into the blogosphere, what would Chevy do?

DETROIT IS NOT A PLACE you associate with revolution, in advertising or anything else. It’s been three-quarters of a century since the spirit of innovation held sway here, and the decline of the US auto industry is writ large in the streets. To drive from Chevy’s ad agency in the white-flight suburb of Warren to General Motors’ headquarters downtown is to pass from car dealerships and fast-food chains to collision centers and pawnshops and finally into a dead zone of boarded-up buildings and overgrown lots. Rising Oz-like out of this wasteland is GM’s towering Renaissance Center, a glittering ’70s-futuristic office complex that looks like the last bastion of an embattled civilization. And at the entrance to RenCen, proudly displayed in a glass-enclosed pavilion, is one of the most profitable vehicles in GM’s lineup: a massive, strapping Chevy Tahoe. “It’s such a strong brand,” says Kim Kosak, Chevy’s ad director. “And it’s a loved brand.”

Out in Warren, in the offices of the Campbell-Ewald advertising agency, they have to figure out how to channel this love. The firm has handled Chevy’s advertising ever since Mr. Campbell and Mr. Ewald met Louis Chevrolet in 1914, and it is understandably sensitive to suggestions that its approach has gone stale. “When the consumer carries the message, it’s really powerful,” says Ed Dilworth, one of Campbell-Ewald’s top execs. As proof, he cites a recent study from the Pew Internet and American Life Project, which shows that more than a third of all Internet users have posted something on the Web. What’s more, the people doing all this uploading come from every income level and ethnicity — a big change from four years earlier, when such activity was largely restricted to a male technophile elite. “Right now, consumers are engaged with new forms of media in a way they haven’t been before and probably won’t be forever,” Dilworth says. “That is an opportunity.”

Out in Warren, in the offices of the Campbell-Ewald advertising agency, they have to figure out how to channel this love. The firm has handled Chevy’s advertising ever since Mr. Campbell and Mr. Ewald met Louis Chevrolet in 1914, and it is understandably sensitive to suggestions that its approach has gone stale. “When the consumer carries the message, it’s really powerful,” says Ed Dilworth, one of Campbell-Ewald’s top execs. As proof, he cites a recent study from the Pew Internet and American Life Project, which shows that more than a third of all Internet users have posted something on the Web. What’s more, the people doing all this uploading come from every income level and ethnicity — a big change from four years earlier, when such activity was largely restricted to a male technophile elite. “Right now, consumers are engaged with new forms of media in a way they haven’t been before and probably won’t be forever,” Dilworth says. “That is an opportunity.”

The Tahoe campaign was a bid to seize that opportunity. “Chevrolet is one of the most aggressive experimenters in our client base,” says Dilworth, who led online advertising efforts for Electronic Arts and Genentech before he moved to Detroit. “They have an appetite for risk. They want to shake things up.”

Not that Chevy was the first advertiser to invite the consumer into the creative process. In spring 2004, Burger King brought people partway in with its “subservient chicken” campaign, which let visitors to a Web site type in a command and watch a guy in a chicken suit do anything they asked — as long as it corresponded to one of 400 prerecorded moves. That summer, Converse got in the game as well, but instead of a gimmick it offered a challenge: Make a 24-second video about us and it could end up on our Web site or even on TV. “We were all quite nervous,” says Mike Shine, creative director of Butler, Shine, Stern & Partners, the tiny Marin County, California, agency that came up with the idea. No one knew whether people would participate or, if they did, whether they’d send in anything good. The answer, some 2,000 submissions later, was yes on both points.

Converse — best known for its Chuck Taylor high-tops, the sneaker of choice for nonconformists from Jackson Pollock to Kurt Cobain — was an ideal candidate, an antibrand whose passionate followers could have been alienated by conventional advertising. “There are not many brands that have that connection,” says Shine, who lives north of San Francisco and goes to the hippie-holdout town of Bolinas to surf. “I would be stunned if people felt really attached to the Tahoe brand. There isn’t a community there.” Oh, and another thing: “I think brands should move on and stop asking people to participate. It’s been done.”

Back at Chevy, however, people thought the potential of consumer-generated advertising had barely been tapped. True, Tahoe drivers don’t much resemble Converse wearers: The Tahoe is a mass-market SUV that appeals to outdoorsy types with large families and boats, particularly in the Midwest and the South. But everybody likes being asked for their input, and Tahoe got nearly 15 times as many submissions in four weeks as Converse got in two years.

Chevy had already enlisted Internet users for its 2005 introduction of the HHR, a retro-style SUV along the lines of Chrysler’s PT Cruiser. After almost 1,300 people submitted photos and videos promoting the new vehicle, Chevy decided it was time to try this stuff where it really mattered — on the Tahoe, whose astronomical profit margin (about $10,000 per vehicle according to one estimate) makes it critical to the success of Chevrolet and its parent, GM. The Tahoe had just gotten its first makeover in years — serious styling, luxury seats — and its relaunch was at the top of GM’s agenda. So they decided to pull out all the stops: “The Apprentice, for prime-time brand awareness,” explains Kosak, the ad director, “and digital, because everybody is into digital.”

Consumer research showed a high correlation between Apprentice viewers and potential Tahoe purchasers. So Chevy bought an episode — not just commercial time but the entire show, which would feature a cutthroat team of Donald Trump wannabes plotting ways to sell dealers on the many virtues of the new Tahoe.

The real-life job of figuring out how to tie that in with an Internet campaign fell to Stefan Kogler, Campbell-Ewald’s creative director for new media. “If you think about the program,” says Kogler, a 42-year-old Detroiter with a degree in new media from the Art Institute of Chicago, “it’s people participating in a task, and we all get sucked into that. Is there any way we can translate that online?”

And so began the Tahoe’s Web-based ad contest. In spots that aired during the special episode of The Apprentice, viewers were urged to go to a newly built microsite, Chevyapprentice.com, and create ads of their own using the video and simple editing tools posted there. “The ‘subservient chicken’ was a trailhead, or maybe a rabbit hole,” Kogler says. “It empowered people, and this was sort of the same thing. You get an immediate emotional response. You get the bragging thing — ‘Look what I did!’ They want to share it with you.”

Once Tahoe-bashers discovered that Chevy had handed them a bully pulpit, they quickly went to work, posting attack ads on the Chevy site and spreading them to YouTube and other outlets. It didn’t take long for bloggers and reporters to realize that something weird was going on over at Chevyapprentice.com. At first, everyone assumed it was just another case of a big corporation not “getting it” about the Internet. Then, when the ads weren’t yanked down immediately, they figured Chevy was too clueless even to notice what was happening on its own site. Only gradually did it dawn on people that Chevy had no intention of removing the attack ads.

In fact, Kosak and her team had assumed all along that they’d get some negative responses, and they decided they’d lose all credibility if they pulled any of them down. Ed Peper, Chevy’s general manager, pointed out in a post on GM’s FastLane blog that the Tahoe can run on ethanol and gets better gas mileage than other large SUVs, but as far as Chevy was concerned, that was that. As Kosak puts it, “We don’t take uncalculated risks.”

BY ANY OBJECTIVE MEASURE, the Tahoe Apprentice campaign has to be judged a success. The microsite attracted 629,000 visitors by the time the contest winner, Michael Thrams from nearby Ann Arbor, was announced at the end of April. On average, those visitors spent more than nine minutes on the site, and nearly two-thirds of them went on to visit Chevy.com; for three weeks running, Chevyapprentice.com funneled more people to the Chevy site than either Google or Yahoo did. Once there, many requested info or left a cookie trail to dealers’ sites.

Sales took off too, even though it was spring and SUV purchases generally peak in late fall. Since its introduction in January, the new Tahoe has accounted for more than a quarter of all full-size SUVs sold, outpacing its nearest competitor, the Ford Expedition, 2 to 1. In March, the month the campaign began, its market share hit nearly 30 percent. By April, according to auto-information service Edmonds, the average Tahoe was selling in only 46 days — quite a change from the year before, when models languished on dealers’ lots for close to four months. Even the hooting among marketing pros died down after Scott Donaton, the editor of Advertising Age, asked in a column for a show of hands from all those who think the campaign proved the dangers of user-created content. “Ah, yes,” he wrote, “there’s quite a few arms raised — you’re all free to go, actually; the marketing business doesn’t need your services anymore. We have a toy railroad set as your lovely parting gift.”

Donaton was taking aim at central tenet of “golden age” mass-media marketing: that by controlling the ad message, Madison Avenue can somehow control perception of the product. “When you do a consumer-generated campaign, you’re going to have some negative reaction,” Dilworth says. “But what’s the option — to stay closed? That’s not the future. And besides, do you think the consumer wasn’t talking about the Tahoe before?” They were, of course; the difference is that in the YouTube era, the illusion of control is no longer sustainable. “You can either stay in the bunker, or you can jump out there and try to participate,” he says. “And to not participate is criminal.”

The era of control is over. “You can either stay in the bunker, or you can try to participate. And to not participate is criminal.”

December 1, 2006

December 1, 2006