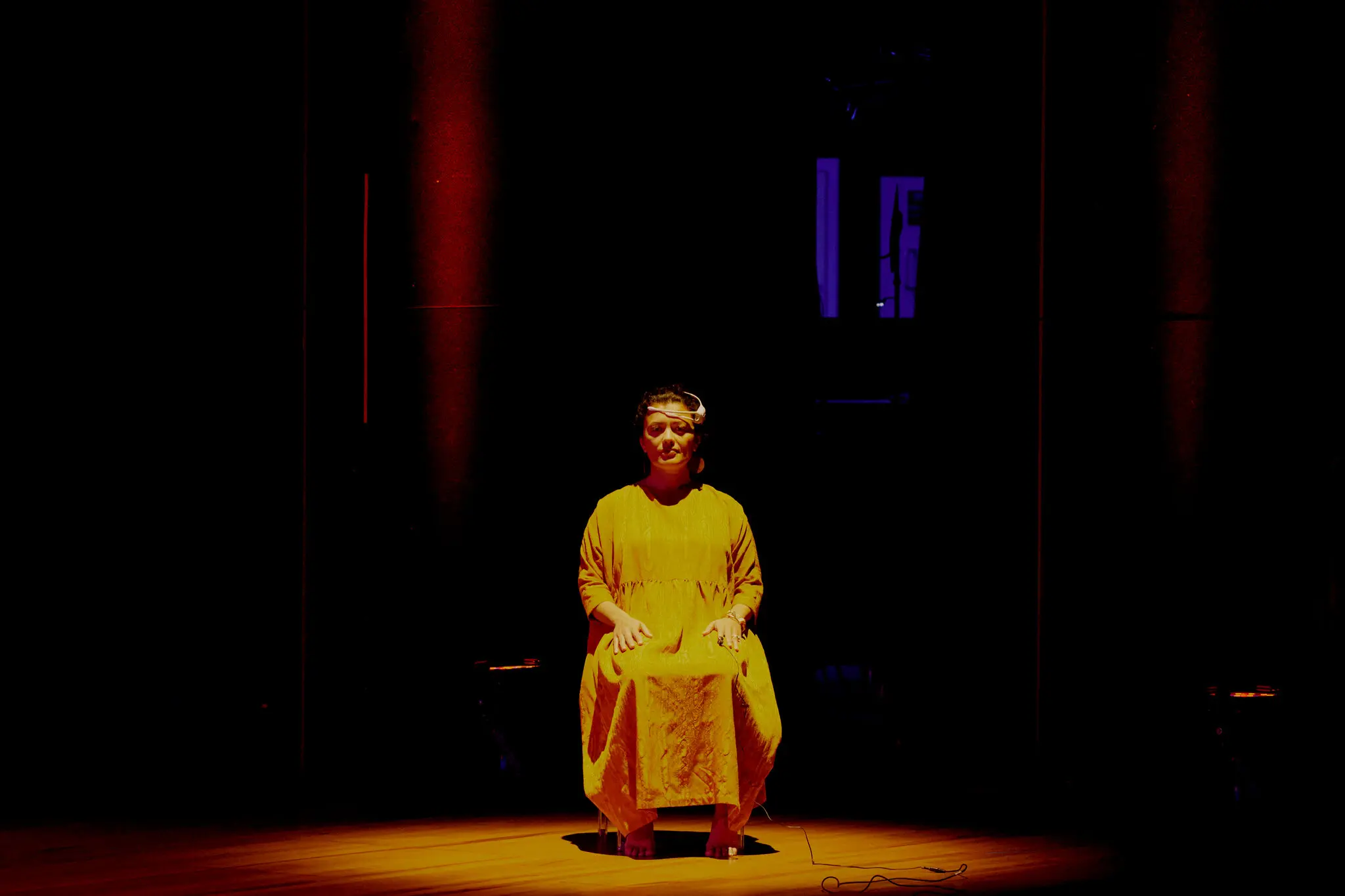

The shape of things to come: Spielberg seated before a scene from his version of H.G. Wells’ tale of extraterrestrial aggression.

FIRST, THE WIND ROSE. Then the attacks came — the terrifying electrical storms, the massive electro-magnetic pulse that stopped phones, cars, and computers, the vast, rippling waves of energy that zapped everything in sight. Now, days later, Ray Ferrier and his 10-year-old daughter Rachel are caught in a crowd of people stumbling down a war-ravaged New England street, picking their way around overturned vehicles and fires that belch acrid black smoke. Faces are smeared with mud, blood, and the ashes of vaporized friends. Everything in sight — walls, fire escapes, even the Revolutionary War statue in a little park nearby — is covered with a strange, leafless plant that looks like a crimson spiderweb. Soldiers from the crack 10th Mountain Division wave the refugees forward, but a wrecked Humvee in their midst punctures any illusion of control. What happened here was the work of weapons no humans possess.

“And cut!” booms a voice from a small blue tent. The movie camera, a big, boxy eye at the end of a very long neck, recedes toward the park. The ruined street is in fact overshadowed by the gleaming high-rises of downtown Los Angeles. Steven Spielberg emerges from the tent, cigar stub between his fingers, blue baseball cap on his head. “Great, guys,” he says, as Tom Cruise and Dakota Fanning walk toward the tent. “That was perfect!”

It’s day 69 of the 72-day shoot for War of the Worlds, Spielberg’s interpretation of the classic H. G. Wells alien-invasion tale. On June 29, the film will open on thousands of screens worldwide. The entire production, from location scout to final cut, will have been completed in just 10 months — half the time of a typical blockbuster. Why the rush? Spielberg and Cruise were eager to make the movie, and when they both found unanticipated holes in their schedules after other projects fell apart, they decided to go for it. But they had to move fast, because the studio was counting on Cruise to pack ’em in for the all-important July 4 weekend. Welcome to Hollywood: When a mega-director and a mega-star find themselves in alignment with a mega-release date, extraterrestrial aggressors have to fall in line.

It’s day 69 of the 72-day shoot for War of the Worlds, Spielberg’s interpretation of the classic H. G. Wells alien-invasion tale. On June 29, the film will open on thousands of screens worldwide. The entire production, from location scout to final cut, will have been completed in just 10 months — half the time of a typical blockbuster. Why the rush? Spielberg and Cruise were eager to make the movie, and when they both found unanticipated holes in their schedules after other projects fell apart, they decided to go for it. But they had to move fast, because the studio was counting on Cruise to pack ’em in for the all-important July 4 weekend. Welcome to Hollywood: When a mega-director and a mega-star find themselves in alignment with a mega-release date, extraterrestrial aggressors have to fall in line.

Thirty years ago, when Spielberg was a novice director shooting Jaws on the open ocean with a malfunctioning mechanical shark, he ran 104 days over his shooting schedule and nearly 300 percent over budget. Now, with Hollywood hooked on the blockbuster mentality that Jaws helped create, blowing the schedule is not an option. Paramount and DreamWorks are laying out some $130 million to make this movie, and millions more to market it. Theaters are being booked on six continents. Trailers are being cut, TV and print ads assembled, publicity campaigns orchestrated, all in hopes of creating the most spectacular opening possible — maybe even beating the record $180 million six-day haul set last July 4 by Spider-Man 2.

To make his deadline, Spielberg relied on people he’s worked with for years, from the cinematographer he first employed on Schindler’s List to the visual effects chief he’s used since E.T. He also embraced digital technology more firmly than ever, using tools like previsualization in innovative ways and giving Industrial Light & Magic a mere seven months to complete a year’s worth of effects. ILM responded by hurling people at the project, and by rolling out a proprietary — and heretofore untested — new software package called Zeno that streamlines the production pipeline. “Technology has been our friend,” says the film’s producer, Kathleen Kennedy, a longtime Spielberg collaborator who’s carefully eyeing this morning’s progress. “Still, I don’t think anybody other than Steven could have done this. He’s the fastest director I’ve ever worked with.”

Spielberg himself seems as calm as the action on set is chaotic. He admits, though, that the pace has been frenetic. “I’ve never prepped a movie this quickly, and I’ve never gone so fast in post,” he says, taking a break as four crew members lift his tent and move it for the next shot. “But it works, and it works without sacrificing quality. That’s the amazing thing — we’re not giving anything up. This movie wouldn’t be 5 percent better if I had six more months.” He repeats himself — for emphasis, or for reassurance. “It would not be 5 percent better if I had six more months.”

Saving human civilization: Spielberg and camera operator Mitch Dubin take aim.

THIS IS THE THIRD MAJOR ADAPTATION of the 1898 H. G. Wells novel, a work that posited one of the great what-ifs of popular fiction: What if there were life on Mars, intelligent life far more advanced than any on Earth, and what if these extraterrestrials decided they wanted our planet? Orson Welles’ 1938 radio play told the story through fake news bulletins that interrupted regularly scheduled programming, setting off a wave of hysteria that had listeners dashing into the streets. The 1953 film, produced by sci-fi maestro George Pal, updated it with Martians so powerful that not even the atom bomb could stop them. Spielberg’s War of the Worlds promises to do the same thing the director accomplished with Jaws: awaken a deep anxiety that can be assuaged only by the compulsive munching of popcorn in a darkened theater. This time he’s doing it not with a fake shark, but with computer-generated alien war machines and a story that taps into a strangely modern fear — that we could be destroyed by technologically superior beings who care no more about us than we care about a nest of insects.

Spielberg’s passion for alien-invasion flicks dates back to his years as a nerdy teen in Scottsdale, Arizona. Inspired by late-night TV fare like Earth vs. the Flying Saucers, The Day the Earth Stood Still, and the 1953 version of The War of the Worlds, he made his first alien movie at 17. Titled Firelight, it relied on high school actors, toy Jeeps and tanks, and stop-motion photography to depict an attack on planet Earth. (Don’t look for it on DVD: As an undergrad at Long Beach State, Spielberg left his only copy at a commercial studio where he was hoping to get work.) He always figured he’d tell this kind of story again.

Once established in Hollywood, however, he gave us the benign intelligences of Close Encounters of the Third Kind and the lovable extraterrestrial in E.T. At heart, Spielberg says, he’s always felt that any life-form that spends thousands of light-years traveling through space would have exploration, not conquest, in mind. “My true nature wants me to make E.T. and Close Encounters. But the audience in me wants to make War of the Worlds. For sheer excitement, nothing comes close to warfare between the human race and an extraterrestrial one. It’s bigger than life.”

Paramount has owned the screen rights to Wells’ story since the silent era, when the studio optioned it for Cecil B. DeMille. (“I’d love to have seen his War of the Worlds,” Spielberg says.) George Pal, DeMille’s friend and protege, made his version at Paramount, and remakes were considered off and on for decades. By the early ’90s, Spielberg was so intrigued that he bought the sole surviving Orson Welles radio script. (The police confiscated the other originals after the panic; this one escaped with Howard Koch, Welles’ cowriter, who took it home and slept through the whole uproar.) But he put the idea on hold after the success of Independence Day in 1996, even though the story he wanted to tell was entirely different.

“Audiences can always wrap themselves around special effects — huge sequences of destruction and combat and people fleeing for their lives,” he says. “But that’s a spectacle, instead of a story about people you know in real life. Especially with science fiction, I’m always looking for a way in for the audience. So I don’t populate this movie with generals and presidents and secretaries of defense. I wanted this to be about real people” — like Ray Ferrier, a Newark, New Jersey, dockworker who until recent events spent his days uneventfully operating the cranes that load and unload container ships. “I wanted it to be about how far a father will go to protect his family.”

“I wouldn’t call it graphic. Sometimes what you don’t see is more frightening.”

In December 2003, after discarding one script, Spielberg summoned David Koepp, the screenwriter behind Jurassic Park and The Lost World. They agreed not to set the film in the 1890s, because if aliens had invaded then we’d know about it, and not to identify the aliens as Martians, for the same reason: We’ve been to Mars and nobody’s there. As for Ferrier, Koepp imagined him as a high school athlete who was going to have it all — until he hurt his shoulder, married young, had a couple of kids, and watched his future slip away. He’s a lousy father, but from the moment he sees the explosions behind his house, grabs his two kids, and flees, all he can think about is supplying them with the most basic human needs: food, water, shelter, warmth.

This apocalyptic idea — that in a flash, some weapon we have no defense against could upend our existence — is as resonant a theme in the post-9/11 world as it was in H. G. Wells’ day. In 1898, the European powers — Britain chief among them — were the world’s undisputed masters. What seemed far-fetched about the book was less the idea of creatures from Mars — scientists had been speculating about Martians for 200 years — than the notion that Britons might find themselves defenseless against some technologically superior power. Britannia ruled a quarter of the Earth; its military prowess was as unchallenged as the United States’ is today. Yet Wells had the audacity to imagine its people as defenseless as the natives they were subjugating.

With books like The War of the Worlds, The Invisible Man, and The Time Machine, Wells all but invented science fiction. What’s kept these stories relevant to moviemakers is not just his overactive imagination — Jules Verne could claim that much — but his grounding in science. He’d studied under T. H. Huxley who, along with being Aldous Huxley’s grandfather, was a champion of Darwin and a key figure in the triumph of science over religion in Victorian England. The War of the Worlds is rife with references to scientific issues, from speculations about life on Mars to discoveries in optics. Wells describes the aliens’ heat-ray, which can set buildings ablaze and incinerate humans in a flash, as an invisible energy beam produced “by means of a polished parabolic mirror” — not unlike the laser, which Einstein would postulate two decades later and no one would actually build until 1960. In the end, the Martians are defeated not by humans but by microbes to which they have no resistance — an idea that seems as contemporary today as it was in 1898, when germ theory was still so novel that surgeons often didn’t bother to wear a mask. The microbe defense suggests that any technology, however terrifying and seemingly invincible, has its limits and that indigenous forces have a natural advantage. The red plant crawling over the set is a reminder of this. “The entire ecosystem is engaged,” says Rick Carter, the film’s production designer. “If it didn’t impact us at that level, they wouldn’t be defeated — but it does. We’re the ones who belong here. They don’t.”

Just as the book could be read as a critique of British imperialism, the movie might be taken as a comment on US military actions today. Spielberg, however, is more interested in the quest for survival and the character issues it summons. In writing the screenplay, Koepp saw civilization not as a veneer that hides our animal instincts but as the grid that supports our way of life. How do we behave when the grid is yanked away? Most of us nobly, some less so. This being a Spielberg flick, Ferrier discovers strengths he didn’t know he had. “It’s the best thing that could have happened to him,” Spielberg says. “I’m not sure it’s the best thing that could have happened to the world around him.”

Ray Ferrier and his daughter (Tom Cruise and Dakota Fanning) hang together.

Probably not, judging from the ruinous condition of the set. Several hours into the day’s shoot, the fires have cast a pall that leaves the sun hanging pale and lifeless in the midday sky. Yet though the alien war machines can wreak almost unimaginable havoc, what you see onscreen will not be hyperviolent. “It’s realistic,” Spielberg says, “but I wouldn’t call it graphic. If this movie required the graphic violence that Saving Private Ryan required, I would have done that. But this time I didn’t have to honor the real-time experience of veterans of World War II. And sometimes what you don’t see is more frightening than what you could be seeing.”

ONE THING NOBODY WILL BE SEEING before the film’s release, if Spielberg has his way, is his interpretation of Wells’ alien war machines: The tripods are the production’s biggest secret. Dennis Muren, the legendary visual effects supervisor, promises they’ll have menace to spare. Muren should know — he’s looking at a previsualization of an alien tripod right now on his laptop. A hundred yards away, Spielberg is eyeing the same pre-viz on a laptop in his tent. Previsualizations are computer-animated, scene-by-scene sketches of the movie that incorporate both actors and effects, and this one shows what nobody else on the set can see — a disabled tripod at the end of the street.

“Camera!” Spielberg cries. As he lowers his megaphone, the soldiers start hustling the crowd through the intersection. “Go! Go! Move!” Cruise just stands there, head upturned, gazing speechlessly at the patriot statue in the park and beyond it, at the enormous tripod that will be digitally inserted in postproduction. Muren is here to represent this “invisible actor,” as he puts it — to remind the real actors where the tripods are supposed to be, how big they are, and just how fast the sons of bitches can move.

Prior to War of the Worlds, Spielberg hadn’t used pre-viz to its fullest potential. He left it to subordinates to help plan complicated effects shots. On Minority Report, for example, his production designer used pre-viz for the shot in which robot spiders enter the tenement where Cruise’s character is hiding. Spielberg wanted to shoot from above, and because the pre-viz showed it would work, he saved a couple of weeks and $100,000 by not building out the tenement room on a soundstage. But given the schedule crunch on War of the Worlds, pre-viz has become the bible for the entire production.

Spielberg became a convert when he met pre-viz specialist Dan Gregoire at George Lucas’ Skywalker Ranch in 2003. Gregoire was midway through Revenge of the Sith when he and his team got PCs equipped with AMD’s new 64-bit Opteron microprocessor. Suddenly they were able to pre-viz a sequence of shots in an hour instead of several days. Lucas ended up looking over Gregoire’s shoulder and making changes on the spot, almost as if he were directing actors on a set. So when Spielberg signed on to make War of the Worlds, one of his first calls went to Gregoire.

The shape of things to come: Spielberg seated before a scene from his version of H.G. Wells’ tale of extraterrestrial aggression.

For War of the Worlds, Gregoire took real-time pre-viz on the road. “This backpack is my office,” he says, sitting in a tent near Spielberg’s and holding up a black nylon bag stuffed with gear: a Titanium PowerBook G4, a bright red Opteron-equipped Acer Ferrari laptop, 60- and 250-gigabyte FireWire drives, and a Sony PD100 digital camcorder. Last August, when they were scouting locations on the East Coast, Gregoire would climb into a chopper to photograph potential sites from the air and then take measurements on the ground. Back at Spielberg’s house in the Hamptons, he’d reconstruct these environments on his laptop. In September, he moved into an office near Spielberg’s at Universal Studios and, with the director at his side, mapped out key sequences. At that point, Spielberg himself took over.

“Once all the info goes into the hard drive, I’m able to take a mouse and fly the set,” Spielberg says. “I can do a 3-D cyberspace location hunt and nail my angles. If I want to move the camera 50 feet into the building, all of a sudden we’re doing that. I would have pre-vizzed this picture even if it had been a 2006 release — but I would not have made this release date had I not pre-vizzed the picture.”

Gregoire’s work also gave ILM a head start on the effects. As soon as he finished a pre-viz, Muren would transmit it to the ILM studios in Northern California, where graphics specialists used it to start mapping out the effects for that scene. To give them even more time, Spielberg plotted his shoot so most of the effects-heavy sequences came first. ILM put some of its most experienced people on the project — 50 effects artists at first, then, once Revenge of the Sith was completed, 150-plus artists and another 50 support personnel. “This was the tightest job we’ve had,” Muren says.

Another thing that helped keep Spielberg and company on schedule was ILM’s Zeno software package — the first major overhaul of its proprietary visual-effects pipeline since the mid-’90s. Previously, ILM effects artists used a dozen or so programs — one to model creatures, another to light them, a third to simulate explosions, yet a fourth to put it all together into a single image. Zeno, developed over the past seven years by Lucas’ in-house programmers, puts all of these components onto a single platform with a common user interface. The big advantage is speed: Now the person who creates the aliens can light them as well. It also means fewer bottlenecks and fewer opportunities for information to get lost or misunderstood in transmittal from one animator to the next. And because the software used for, say, creature development employs the same algorithms as the software that simulates explosions, compositors can marry creatures and explosions without spending extra hours adjusting for those minor mathematical discrepancies that can shatter the illusion of reality. All that was great — but it also meant that, aside from dealing with the computer crashes that come with any new software system, the artists had to learn a whole new way of working.

Traveling between the shoot and ILM, Muren translates Spielberg’s directives to the effects artists. But he’s been formulating his own vision of War of the Worlds for a long time. As a grade school kid in the suburbs of Los Angeles during the ’50s, he says, “I grew up with this movie.” Often he’d look up effects artists in the phone book and cold-call them, but it wasn’t until last year that he got the scoop on The War of the Worlds from a friend of its original production designer. “They wanted to do tripods in 1953, but they couldn’t figure out how to make them walk,” he reports — so they switched to hovering saucers, then built models and suspended them above the soundstage on wires so they seemed to float above the ground. “Now we have the technology to do it.”

Coming up: Indiana Jones 4. “If anyone can get me to shoot on digital, it’s George.”

Spielberg’s tripods are entirely computer generated, but the menace they project comes from many factors — “from the way they move, from the lighting, from the camera angles, from the darks in the photography,” Muren explains. “We wanted to make characters out of them.” For the surrounding cityscapes, the f/x crew relied on miniatures — buildings 4 feet tall standing in for buildings 40 feet tall, just as in the ’50s. “We have some very large objects — I can’t say what — that get destroyed,” Muren says. “This is not a big sci-fi destruction movie, but the destruction is pretty enormous at the personal level. It’s as though the aliens are here, there — you’re trying to get to safety, and you don’t quite know where they are.”

NEITHER PRE-VIZ NOR ZENO has softened Spielberg’s almost fetishistic appreciation for film — not just shooting on film, which is still the norm in Hollywood, but editing on film, which is all but unheard-of anymore. For most directors, editing a huge, rush picture on film would be a suicidal luxury; for Spielberg, who’s worked with the same editor since 1977, it’s just a luxury. “I love being able to have an actual byproduct of photochemistry in the room with me,” he says. “I love the smell of it. I love being able to hold up the film and see actual frames. I love hearing the butt-splicer cut through the celluloid. I’ll do everything else in the digital era, from pre-viz to digital dinosaurs. But there are certain things I’m hanging on to tenaciously.”

Lately, Spielberg and Lucas have been arguing over whether to shoot the fourth episode of Indiana Jones, one of the many projects on Spielberg’s to-do list, in digital. “If anybody is able to get me to shoot on digital, George is the one,” he says. “But do we want to evolve things to a clarity that is indistinguishable from real life? Movies suspend reality — suspend and extend reality. We’re interpreters. If things get too clear, it won’t look like there’s an interpreter.”

Suddenly an assistant materializes and hands Spielberg a cell phone. The Oscars were handed out last night, and the airwaves are abuzz with mutual adulation. “Clint,” Spielberg cries, turning back to the set. “Man, you must be flying high! Congratulations!”

It’s late in the day, and Spielberg has one more shot to squeeze in before sundown. Tomorrow he moves to the hills outside Los Angeles to finish one last scene — an all-out battle between the alien war machines and everything the US military can muster against them. Ray Ferrier and his kids, trying to escape the devastation without benefit of radio, cell phone, or motor vehicle, stumble into the fighting unawares. Most of this sequence was filmed last fall in rural Virginia, but the tight shots are being done here in southern California on the final three days of the shoot. Meanwhile, 350 miles to the north, ILM’s effects artists are bracing for a fresh onslaught of mayhem. ◆

WW4: The Evolution of Alien Invasion

From “The Angry Red Planet” to “Independence Day,” from Tim Burton (who directed “Mars Attacks!”) to Richard Burton (who narrated the rock musical), the H.G. Wells classic has inspired countless imitators and homages. Here’s how the most memorable remakes stack up against the original.

| 1898 | 1938 | 1953 | 2005 | |

| THE BRAINS (THE MEDIUM) |

H.G. Wells (book) |

Orson Welles (radio) |

George Pal (film) |

Steven Spielberg (film) |

| FIRST ENCOUNTER | Woking, England | Grovers Mill, New Jersey | Linda Rosa, California | Newark, New Jersey |

| FIRST INEFFECTIVE DEFENSE | Horse artillery | 22nd Field Artillery | Bombers and ground forces | Entire US arsenal |

| SECOND INEFFECTIVE DEFENSE | Warship Thunder Child | Eight-plane Army bomber squadron | Air Force YB-49 Flying Wing with atomic bomb | Sporadic guerrilla action |

| MAJOR CITY DESTROYED | London | New York | Los Angeles | Newark . . . |

| THE RESULT | Millions of copies in print | Mass hysteria | Oscar for special effects | No competition for July 4 weekend |

June 13, 2005

June 13, 2005