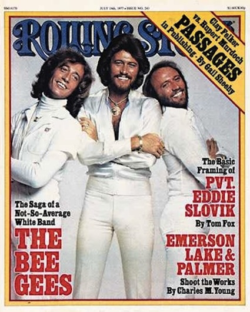

Rolling Stone’s cover story on the Bee Gees was reported in February 1977 in three separate locales: Robin Gibb in London, Maurice at home on the Isle of Man, and Barry in France at the legendary “Honky Chateau”— the Château d’Hérouville, then a recording studio. Robert Stigwood was interviewed by phone. Cover photo by Francesco Scavullo.

LONDON: 67 BROOK STREET, MAYFAIR, is sometimes referred to as the house that Cream built. It predates Cream by quite a bit, actually, but that’s not what they mean. What they mean is that this is the house that Cream bought. The man they bought it for is Robert Stigwood.

But Stigwood hasn’t spent much time in London lately; the pressures of running an international entertainment empire keep taking him to New York and Los Angeles and Bermuda – places like that. His staff carries on bravely, but there’s an emptiness they cannot fill, an emptiness which takes the form of a large rear office on the first floor – the office with the crystal chandelier, the fake fireplace and an inch-thick slab of glass, set atop four stone lions, which serves as a desk. It is Stigwood’s office, and it has been mostly empty for about five years now.

But Stigwood hasn’t spent much time in London lately; the pressures of running an international entertainment empire keep taking him to New York and Los Angeles and Bermuda – places like that. His staff carries on bravely, but there’s an emptiness they cannot fill, an emptiness which takes the form of a large rear office on the first floor – the office with the crystal chandelier, the fake fireplace and an inch-thick slab of glass, set atop four stone lions, which serves as a desk. It is Stigwood’s office, and it has been mostly empty for about five years now.

At the moment, however, Al Coury, president of RSO (Robert Stigwood Organization, naturally) Records, and Robin Gibb, one of the Bee Gees, are sitting in two of Stiggy’s leather chairs having what Robin would call a “chin-wag.” This particular chin-wag is focused on the Bee Gees’ studio work in progress at the Honky Chateau in France and on the lifestyle that prevails there.

Al Coury, inquisitive on his first visit to London since taking over RSO Records a year ago, stands up to sniff the air in Robert’s office. “All those famous albums,” he sighs. “All those deals . . .

“You must find yourself spending a lot of time on the music,” Coury observes. “Well,” Robin retorts, “there’s nothing else to do.”

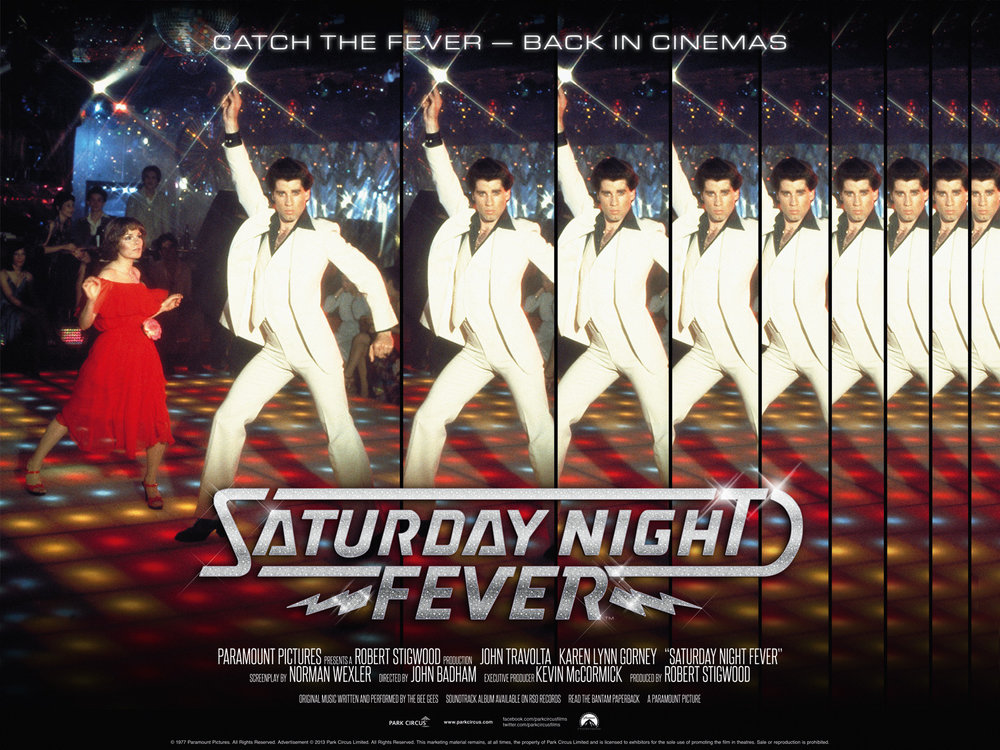

It is now early February; since the beginning of January the Bee Gees have been polishing their new album, Here at Last . . . Bee Gees . . . Live, and writing material for Saturday Night Fever, a film Stigwood is producing for Paramount. In July they will go to Toronto to record the soundtrack. In September, October and November they’ll be on location for the filming of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, an RSO musical extravaganza in which they’ll costar with Peter Frampton.

The demand on the Bee Gees for recorded product has been strong. Children of the World, their last album, is very close to going double platinum, and to intensify the action RSO recently released two oldies albums – a greatest-hits package and a one-disc version of Odessa, their commercially unsuccessful concept album recorded in 1969. Bee Gees . . . Live, recorded in L.A. in December, is their only live LP, but it was required by their new five-year, eight-album contract with RSO – and besides, as Robin puts it, “These particular tapes warranted being brought out.”

Clearly, these people are in business – show business. “Show business,” says Robin Gibb, “is something you have to have in you when you’re born.” When Robin and his two brothers, Maurice and Barry, were born on the Isle of Man (their father was the bandleader on the IOM-Liverpool ferry), show business was a grand and glorious tradition. It isn’t the Bee Gees’ fault that in the late fifties, when their act was just getting started in Australia, show business lay dead and pitiful like a fractured racehorse. And you can’t fault them for never quite comprehending that. The Bee Gees, after all, were never conscious of what was going on around them; that was part of their appeal. Even in their heyday they were throwbacks, the last of the sixties innocents.

Actually, it’s a little unfair to call 67 Brook Street the house that Cream built. Cream and the Bee Gees together formed the foundation of the Stigwood Organization. The Bee Gees paid for these gracious Regency digs as much as anybody. The Bee Gees just weren’t very – noticeable. And it’s always been that way.

Robin Gibb is sitting behind Robert Stigwood’s desk, looking dwarfed, happy, but also slightly nervous. After 20 years in show business and ten years of international stardom, it is still characteristic of him to be uncomfortable about interviews.

I mention songwriting and Robin breaks in indignantly: “No one has ever talked to us about our songwriting! That’s always amazed me. I don’t think people even realize that we write our own songs.

“It doesn’t bother me, but – you know that Playboy poll? It has a songwriting section, and this year we’re not even in it. There’s people in there who haven’t had any success for the last two years. We’ve had two platinum albums, all our own music, and three hit singles practically at one time on the Hot 100. At this moment we stand to be given the, uh, whatever that award is for songwriting. It’s just that they don’t know their business. They don’t make it their business to know how many records the Bee Gees have written. I call it just – musical ignorance!”

The Bee Gees’ songwriting talent is quite extraordinary. They write hits the way most people write postcards. They write them on demand – any time, anyplace, on any subject. They’ve written a lot of them while sitting on staircases. “Jive Talkin’,” one of their latest hits, was written on a causeway between Miami and Miami Beach. “I Can’t See Nobody,” one of their early hits, was written in the dressing room of a club. The Bee Gees were in their mid-teens at the time, sharing the dressing room with a stripper.

When they were all at the Honky Chateau, Stigwood rang up with instructions for the theme song he wanted written for Saturday Night Fever. According to Barry Gibb, the instructions went like this: “Give me eight minutes – eight minutes, three moods. I want frenzy at the beginning. Then I want some passion. And then I want some w-i-i-i-ld frenzy!” They wrote the song “Stayin’ Alive” in two hours; it fills the bill. A disco tune, it has real jive precision, like a sleek black Mercedes with an ashtray full of coke. Saturday Night Fever is about the night life of some Italian disco dudes in Brooklyn, but the Bee Gees didn’t know that when they wrote “Stayin’ Alive.” They say it was just an accident that the song they came up with is as well-tailored lyrically as it is musically: Whether you’re a brother or whether you’re a mother/You’re stayin’ alive, stayin’ alive.

They’ve written four other tunes for the film – “quite staggering,” says Stigwood, “particularly as they did it all in a week.” Robin is nonchalant. “It’s obviously easy,” he says. “We did it.” They did it the way they always do: sitting down together, throwing out lines, not writing anything down – none of them read or write music – storing it in their heads until they’re ready to record. “We’ve all got the same kind of brain wave,” Robin explains.

Stigwood has that kind of brain wave too, although his seems to be tuned to a slightly finer signal. After the band sent him demo tapes of “Stayin’ Alive,” for example, he wanted to know if they could stick a brief, slow piece in the middle of the wild frenzy. “Robert has this thing about songs that break up in the middle with a slow piece,” says Robin. “He did the same thing with ‘Nights on Broadway.’ ” Stigwood is as modest as the brothers themselves. “I can’t claim any contribution to their songwriting,” he smiles. “I wish I could. I’d be taking their royalties, I assure you.”

Stiggy is right to be modest. The Bee Gees have been writing songs that way since Robin was seven years old. They were living in Manchester then – twin brothers Robin and Maurice, older brother Barry, older sister Lesley and baby brother Andy, all living with their mother and dad, the bandleader. They were part of a little singing troupe that came on in a Manchester cinema before the queen – before the picture of the queen they show between movies, that is.

They picked their name in 1958. Gibb père had moved his family to Brisbane earlier that year in an attempt to escape the grim lot of a working-class bandleader in postwar England. The brothers moved on to bigger Australian venues – places like army clubs, where they performed as a novelty act.

Their father, Robin says, didn’t push them into show business – but once he saw they had it in their blood, he threw himself behind them. Barry and the twins quit school; their father abandoned his career; and the Bee Gees got serious about what they were doing.

Harmonies they already had. Their father taught them how to work the audience. He was good at reading people, too; he could tell if somebody was up to no good. He took care of them. “If he would’ve had his opportunity in his own life,” says Barry, “he would have been a big star. But he didn’t, so it was through us that he was going to make it.”

In August 1962 the brothers signed with Festival Records, one of Australia’s major labels. A few months later the family moved to Sydney, the center of the record industry. Over the next four years Festival released a dozen Bee Gees singles and one greatest-hits album. They all flopped. Finally, the label boss told them they’d have to go. But then they met a fan named Ozzie Byrne who owned a recording studio. Ozzie gave them unlimited studio time – unlike Festival, which typically whisked them in and out in 30 minutes – and the band came up with “Spicks and Specks,” their first Number One single in Australia.

“It doesn’t matter if you become the biggest thing in Australia,” Maurice says now, “because the furthest away you’re known is New Guinea and Tasmania.” Spicks and Specks was released in November 1966; in January, the Bee Gees booked passage with Ozzie Byrne to England. Their parents went along as well. “They wanted to stay in Australia,” Robin says, “but we said no.”

Before they left, the Gibbs had sent some of their records to NEMS Enterprises – Brian Epstein’s company, the one that managed the Beatles. The family arrived in London on a Tuesday, moved into a house on Friday, and the following Monday received a call from Robert Stigwood, managing director of NEMS. He wanted to see them immediately.

“I loved their composing,” Stigwood recalls. “I also loved their harmony singing. It was unique, the sound they made; I suppose it was a sound only brothers could make.” He gave them a five-year contract to sign, then took them to a studio to make some demos. When the power went off, they sat down on a staircase and wrote “New York Mining Disaster, 1941.” Stigwood immediately booked time in a studio with juice.

“New York Mining Disaster” was released two months after the Bee Gees arrived in England. It became an instant hit – not only in Britain but in the States as well. In July – a month after the Beatles released Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band – they put out “To Love Somebody”; in September, “Holiday”; and in October, Bee Gees’ 1st. By the end of the year, the Bee Gees, none of them yet 20, were major stars.

Stigwood calls this “round one” in the Bee Gees’ career. It involved a lot of ballads, a lot of strings, a string of hits, too much speed and a long period of craziness at the end. The craziness was a predictable result of their short-order stardom, but it was also a pattern for late-sixties rock groups. The Bee Gees simply did what everybody else was doing: they split up and started recording solo albums. Unlike everybody else, however, they were unable to get away with it. They were different. When they squabbled and put out lousy records, people simply forgot about them.

The breakup came early in 1969, just after the release of Odessa. Robin announced his plans to pull out and record a solo album, and Maurice, Barry and Stigwood announced their plans to sue him. All kinds of weird things happened after that. Their drummer left and claimed the right to their name. Barry and Maurice countered Robin’s solo album with an album and a TV special. More than a year went by before Robin, at Stigwood’s urging, called his brothers – and it was another six months before they all got together. “It was a pride thing,” Robin says now.

With Robin, discussing the breakup can still be like poking about in an open wound. Maurice and Barry seem more objective. “It was basically immaturity,” says Maurice. “We weren’t cut out to be solo stars,” Barry adds. “We were cut out to be the Bee Gees. Somebody in his almighty wisdom knew that, whether we did or not.”

Round two of the Bee Gees’ career looked fairly promising at first: there was a lot of bad press, especially in Britain, but there were also some hits – like “Lonely Days” and “How Can You Mend a Broken Heart?” Then their singles started dying, and round two began to stall.

The problem, they realize now, was simple: they’d gotten into a rut. Nobody wanted their ballads anymore. Their initial reaction, naturally, was to record more of them, in an album called Mr. Natural. When that didn’t work, they tried it again. But when they sent the tapes for their next album to Stigwood, he became angry. “I got the feeling they weren’t really listening to what was happening in the industry anymore,” he says. “So I flew down and had a confrontation with them.”

Stigwood’s confrontation must have worked, because the next tapes they sent up were for Main Course. The Bee Gees credit producer Arif Mardin with the breakthrough. “He showed us the right track,” says Maurice. “This was the track leading to R&B and hits, and that was the track leading to lush ballads and forget it, and he just shoved us off that track and right up this one.”

The Bee Gees had first worked with Mardin on Mr. Natural, the stiff of ’74, but it wasn’t until Main Course that people noticed they were teamed with the man who’d made it work for the Average White Band. The brothers have easily accepted the sound he led them to: Maurice is delighted; to Barry it’s “pleasant and energetic”; Robin sees it as a form they’ve helped inject with quality.

And, of course, it was a real smart marketing move. It gave them a completely new audience and it gave them a dynamic new tag for their old one.

The Bee Gees have this theory that the disco switch wasn’t really a switch, just a refinement. “We were always writing the kind of music we do now,” Robin says, “but we weren’t putting it down right. We were writing R&B, but we weren’t going in an R&B direction.” Other times, however, they are more direct. “Who says you can’t play different kinds of music?” Barry demands. “You just do what you want to do. We play different kinds of music because we put our hearts into different kinds of music.”

THE BEE GEES RECEIVED A JOLT LAST YEAR when they returned to Miami to record the followup to Main Course. A day or two after they arrived at Criteria Studios, they got a call from Atlantic Records in New York. It was bad news: Mardin wouldn’t be able to produce the record. “That really broke us up,” says Maurice. Says personal manager Dick Ashby, “It struck us that Atlantic was trying to use us to get to Robert.”

Some months earlier, Al Coury, newly appointed to his post as president of RSO Records, had announced a worldwide distribution/marketing pact between RSO and Polygram, Inc., the giant German-based multinational record corporation. The announcement followed several months of negotiations between Stigwood and Polygram on the one hand and Stigwood and Warner Communications, Inc., on the other. It meant that Atlantic Records, a Warner subsidiary, would lose U.S. marketing rights to RSO product – rights it had enjoyed since 1974, when RSO Records had been created as an Atlantic custom label.

After an unsuccessful tryout with Richard Perry, the Bee Gees decided to return to Miami, where they could at least use the same studio and the same engineers they’d had on Main Course. It was a good idea; in fact, one of the engineers, Karl Richardson, and Albhy Galuten ended up as coproducers. The album they produced was Children of the World.

Mardin, meanwhile, was rooting from the sidelines. Says Maurice, “Everybody at Atlantic was telling him, ‘They won’t do anything without you,’ and Arif was saying, ‘Don’t worry, these guys will do it.’ He told us all this on the phone. We were saying, ‘Can we send you the tapes to see what you think?’ He said, ‘Well, I have to hear them some time, but don’t tell anybody.’ So we sent him the tapes and he sent a note back saying, ‘They’re fantastic – don’t do a thing to them.’”

The Bee Gees’ next studio production is not likely to be as traumatic, since the Galuten-Richardson partnership proved so felicitous. Sgt. Pepper should make up for it, however. Stigwood has already fired its first director, Australian-born TV whiz kid Chris Beard, one of the creators of The Gong Show. “Actually, I’m having a spate of that,” he says. “The other night I fired the Saturday Night director” – John G. Avildsen, who later won an Oscar for Rocky. “It was a terrible coincidence, too. When I was firing him, the message came through that he’d been nominated for an Academy Award – I had to break off and congratulate him in the middle and then carry on with the foul deed.”

The problem was the same with both directors: they wanted to make something different from what Stigwood had in mind. The Sgt. Pepper envisioned by Stigwood and scriptwriter Henry Edwards is a Hollywood musical in the grand tradition, only with Lennon and McCartney where Cole Porter would have been. It’s about Billy Shears (Peter Frampton) and his band (the Bee Gees) and their search for the stolen magical instruments which belonged to Shears’ grandfather – the legendary Sgt. Pepper, whose Lonely Hearts Club Band established the tradition of instant joy Shears’ outfit strives to follow. “It’s a fable,” says Edwards, “about the redeeming power of music.”

Sgt. Pepper is only one of four films Stigwood has slated for production this year, although its $6 million budget commands the biggest bucks. The others are Saturday Night ($3 million), starring John Travolta; Grease ($4 million), number two in Travolta’s three-picture deal with Stigwood; and The Geller Effect – not yet budgeted – which will star key-bender Uri Geller in a dual role that’s part autobiography, part fiction. This represents a sizable jump in film activity for Stigwood, whose previous productions consist of Jesus Christ Superstar, Tommy, Bugsy Malone and Survive!

“It was a combination of good things coming up,” Stigwood explains. But many good things have been coming up for RSO lately, and not just in the film division. RSO Records has been following a “controlled expansion” policy which was not so controlled as to preclude its recent $7 million bid for the Rolling Stones. Major action also seems imminent on the television front, which has been quiet since the failure of Beacon Hill, and Stigwood also holds out the possibility of a leap onto the Broadway stage.

RSO’s metamorphosis from rock management concern to multimedia entertainment empire began in 1968, when Stigwood saw Hair on Broadway and decided to produce it in London. What followed was a string of West End stage productions, two of which – Oh! Calcutta! and Jesus Christ Superstar – are still running after more than five years. In the early Seventies, as the fortunes of his two leading rock acts waned, Stigwood purchased a production company, Associated London Scripts – the people who subsequently developed All in the Family and Sanford & Son. (Producer Norman Lear pays RSO episode fees.) What Stigwood sees ahead is balanced expansion with all sectors interacting – but not expansion beyond the family-company stage.

“Family company” is a term you hear frequently at RSO. At times it seems quite literal: the Bee Gees’ father still handles their lights. Everywhere you look an unusual camaraderie is evident. The people who work here share an enthusiasm that is less than a cause but more than just a well-paying job. It seems to be a cult of personality attached to Robert Stigwood himself.

The sun rarely sets on Stigwood. He is a constant traveler, a bachelor with homes in Los Angeles, New York and Bermuda (alas, the one in London had to be sold for tax reasons), a peripatetic power broker with a penchant for style and a fondness for life in the grand manner. Like Brian Epstein before him, he lives in the Noel Coward tradition – but where Brian pioneered in translating the Coward style to the purposes of the businessman, Stigwood adds a crucial refinement: it is not sufficient just to be a businessman; one must also be a good businessman.

“We believe in working hard and having fun at the same time,” he says. “It’s a way of life for me, and I feel tremendous. I feel very lucky to have the freedom to do the things I want to do. And as I say, my clients are all my friends as well.”

July 14, 1977

July 14, 1977