Until the mid-1990s, America Online was considered too uncool for Wired to cover. An online service that wasn’t the internet? Headquartered in a suburban office park outside Washington, DC? No, thanks. Eventually, however, AOL’s hypergrowth made it too big to ignore. This was the magazine’s first major article on the company.

“WE NEED TO BUILD SOME FRANCHISES,” Ted Leonsis is saying. “We need our own Lion King.” As chief programmer of America Online, with some 6 million members in the US and Europe, Leonsis commands more eyeballs than anyone else in cyberspace — paying eyeballs, at that. And he’s had some impact: The Motley Fool, AOL’s irreverent personal investment guide, is now so influential it can move the market. But if AOL is to confound its critics and counter the perception that the Internet will soon doom it to oblivion, Leonsis needs more. Much more.

In a medium best known for recycling established brands — People Online, Newsweek Interactive, Batmanforever.com — Leonsis wants titles so popular they can spawn hit movies and TV shows, rather than the other way around. He wants tent poles, in Hollywood parlance — properties that can support a lot of overhead, drawing crowds in their own right and generating lucrative spinoffs, as The Lion King has done for Disney and Star Trek has for Paramount. That’s why he’d like to be known as the Brandon Tartikoff of cyberspace, after the onetime Paramount head and NBC programming chief who put The Cosby Show on the air. And why, on an afternoon in late August, the real Brandon Tartikoff is sitting right across the table from him.

In a medium best known for recycling established brands — People Online, Newsweek Interactive, Batmanforever.com — Leonsis wants titles so popular they can spawn hit movies and TV shows, rather than the other way around. He wants tent poles, in Hollywood parlance — properties that can support a lot of overhead, drawing crowds in their own right and generating lucrative spinoffs, as The Lion King has done for Disney and Star Trek has for Paramount. That’s why he’d like to be known as the Brandon Tartikoff of cyberspace, after the onetime Paramount head and NBC programming chief who put The Cosby Show on the air. And why, on an afternoon in late August, the real Brandon Tartikoff is sitting right across the table from him.

Tartikoff has come to AOL’s offices in the northern Virginia suburbs of Washington, DC, to talk ideas. With about 450,000 users logging on every hour from 7 to 11 p.m., AOL is small stuff by broadcast industry standards, where a hit like Seinfeld pulls in more than 30 million viewers for a single half hour. But Leonsis can launch an online “show” for about what it costs to shoot a 30-second commercial. And if it clicks, it’s like a cult novel — a name property that can be ported to some other medium, where the real money is. The Mighty Morphin Motley Fool? If you say so.

Leonsis, a large man whose dark complexion, prominent nose, and dazzling smile make him look like someone Disney animators might have dreamed up for Aladdin, is visibly pleased at having lured such a big fish as Tartikoff to the pond he shares with AOL founder and CEO Steve Case. When Charlie Fink, an ex-Disney exec who runs the development office called The AOL Greenhouse, mentions another star attraction — the comedy team Hecklers Online — Leonsis nearly leaps out of his chair. “These kids just had their one-year anniversary,” he cries, “and Henny Youngman and Milton Berle were on the show to pass the torch. They said, ‘This is like vaudeville — we started on stage, and then we became TV stars and movie stars. You’re starting online when you’re in your 20s, and when you’re 70 you’ll be doing Friar’s Club roasts.’”

“Speaking of roasts,” Fink puts in, “the Hecklers just roasted Ted.”

“I thought they were going to be really tough,” Leonsis laughs, belly quivering beneath a white oxford-cloth Ralph Lauren shirt. “They did ask what were the two dumbest Greenhouse pitches, other than putting them on the air. I said, ‘A personal diary of Steve Case — I don’t think we wanna do that — and Gay and Lesbian Pet Forum. We know pets are hot, and we know gays and lesbians are hot, so we’ll do a gay and lesbian pet forum.’ To which at first I actually said, Hmmm. . . .”

Tartikoff, a slender, graying man in chinos and a blue polo shirt, nods sympathetically. “Listen,” he says, “the hardest thing in an internal pitch session is just getting people to feel like they can open their mouths. We used to start by saying, Let’s go around the room and try to pitch the stupidest ideas possible.”

Leonsis brightens. “We oughta do a marathon pitch session with Brandon: ‘Pitch Me an Idea.’ You have 12 lines — “

“No,” says Tartikoff, “you have 30 seconds.” He reaches for a 2-inch-thick looseleaf notebook labeled “Brandon Tartikoff Projects for America Online” and opens it to a page titled “Pitch Me a Show.”

“You’d really do it?” Leonsis is incredulous. “You’ll sit down and talk to them? Because that would be huge! We’d have to build a stadium!”

Tartikoff isn’t yet ready to commit, but AOL is building anyway. Upstairs at Greenhouse headquarters, five people from the Style Channel (keyword: style), a joint venture with the Disney-owned publishers of Women’s Wear Daily and W, are huddling with AOL programming and creative affairs execs. A team from PlanetOut (keyword: PNO), a gay-oriented start-up, is in from San Francisco to put the finishing touches on its promo campaign, set to launch this fall. A guy from The Knot (keyword: knot), a new program touting “Weddings for the Real World,” is working with AOL technicians to load content. Everywhere you look, clean-cut twentysomethings in jeans and sneakers are racing desperately to grab new members, to keep those subscription fees streaming in, to take AOL to the next stage.

To sign on to AOL is to enter the cyber version of a suburban mall, a carefully modulated environment where the ambience is serenely antiseptic (as long as you don’t venture into the wrong chat room late at night). And for a lot of people, that’s great.

Because this is make-or-break time for America Online. In three years it has emerged from nowhere to become the Goliath of cyberspace, a billion-dollar company that has local dialup numbers in more than 800 cities across the US and Europe and contributes an astounding one out of every three users of the Internet. AOL handles more than 11 million email messages a day. It hosts 7,000 chat rooms nightly and features more than 1,100 proprietary content sites on 21 “channels.” But that out-of-nowhere success has drawn a swarm of competitors, from mom-and-pop Internet service providers to global giants like MCI and AT&T, not to mention a little company called Microsoft.

Their weapon is price — cut-rate, flat-fee connections offering unlimited Internet access for US$19.95 a month or less — and they’re targeting the lucrative, high-usage subscribers whose triple-digit monthly bills have kept AOL’s bottom line black. Flat pricing threatens to make AOL and the few other remaining pay-by-the-hour online services as obsolete as the CP/M operating system. But Case and Leonsis are already gearing up their own flate-rate price scheme. They are also pressing a bold — some might say outrageous — new marketing drive, aimed at pushing membership to 10 million by next August.

And that’s just a warm-up for the real event — a strategic repositioning that, if it works, will put Steve Case and Ted Leonsis up there in the media pantheon with Brandon Tartikoff. Through partnerships with folks like Disney and Time Warner they aim to remake AOL as a vertically integrated behemoth, offering not just access and distribution but content — the new-media equivalent of Tele-Communications Inc. or Viacom. What? Haven’t you heard? “We’re a media company!” Leonsis cries excitedly. “When I hear us compared to Prodigy or CompuServe or an ISP, I say, You just don’t get it.”

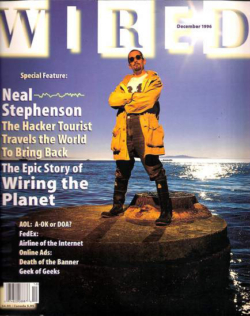

The man who’s giving away floppy disk drives: Steve Case, co-founder and chair of AOL.

Few people do — and for good reason. The online future Leonsis and Case envision is as alien to most of Net culture as northern Virginia’s suburbs are to Manhattan’s Silicon Alley or San Francisco’s Multimedia Gulch. To sign on to AOL is to enter the cyber version of a suburban mall — a carefully modulated, vaguely cutesy-poo environment where the ambience is serenely antiseptic (as long as you don’t venture into the wrong chat room late at night) and the impulse to consume is stimulated at every stop. For a lot of people that’s great, at least when the system isn’t jammed with too many users fighting over too little infrastructure. But the Web, with its wide-open electronic boulevards and anything-goes mystique, lies just a click away. And at least for now, it’s free.

“It’s not a choice between AOL and the Internet,” Case insists, rehearsing his latest marketing slogan in a large, corner office at AOL headquarters, overlooking fields and pastures and the occasional silo, not far from Dulles airport. “AOL is the Internet and a whole lot more.”

Well, maybe — and there are worse ideas to bet on than the one-stop convenience of a suburban mall. But the metaphor Case and Leonsis prefer is cable television, where you start out as an access provider to millions of homes and a distributor of brand names like CNN. Then, if you’re smart, you diversify into content — as TCI and its subsidiary, Liberty Media, did when they bought a chunk of Turner Broadcasting System, or as Viacom did when it started MTV, VH1, and Nickelodeon. Why you’d want to imitate TCI, with its languishing stock price and mountain of debt, is anybody’s guess. But if you go really big time, the way Viacom did when it won control of Paramount, who knows? “Maybe we’ll start to be known as the fifth network,” Leonsis muses. “ABC, NBC, CBS, Fox, and AOL.”

Keyword: churn

Vienna, Virginia, the bionic suburb where in 11 years America Online has grown from small-time start-up to e-world kingpin, may not be the most obvious place to launch a global media empire, but it suits AOL. Is it by accident that you have to take a toll road to get there from Washington? Or that the company’s old offices are just down the highway from one of the biggest shopping centers in the world? Or that its sleek new $32 million headquarters, 22000 AOL Way, are quite literally in the middle of no place — in an unincorporated area called Dulles, which doesn’t exist on the map but, with barns and farmhouses giving way to condos and office parks, could be almost anyplace? Nowhere and anywhere, anywhere and everywhere, AOL is one potential endpoint of the network paradigm, the wired future as subject to brand management, a Coca-Cola vision of 21st-century community.

“Our goal,” says Leonsis, “is to be ubiquitous.”

No problem. Former competitor Anthea Disney, who was editor in chief of News Corp.’s ill-fated online service (which downsized into a Web site last spring), says most people don’t even get it that America Online is different from the Internet: “You say online to the American public, they say America Online.”

Yet after three years of soaring stock prices and wildly accelerating growth, the summer of 1996 brought mostly mayhem. There was a systemwide service blackout that made headlines around the world, the resignation of a new president only four months into the job, a federal court settlement in which AOL admitted to nickel-and-diming customers, a seemingly unstoppable tide of junk email, and enough subscribers heading for the doors to make “churn” an industry buzzword. And that’s not even counting the emergence of the Web as a mainstream media phenomenon.

AOL’s strategy has been built on the notion that the Net would remain a cult attraction, unsuited to a mass market that can’t handle anything more complicated than a VCR. “I think consumers are increasingly going to opt for simplicity,” says Case, sliding around in his chair like a restless teenager as his white AOL workshirt rides out of his jeans. “It needs to be easier, not harder. Being able to go to America Online and click on the sports icon and get the best sports services is important, and people are going to do that far more often than they’ll open up a search engine and randomly surf for Web sites.”

Yet as Wall Street and Madison Avenue fall increasingly under the Internet’s spell, as tens of thousands of new Web sites blossom each month, and as the telcos and RBOCs muscle into the access business, the outlook for proprietary online services looks increasingly grim. CompuServe has been hemorrhaging 10,000 members a day. General Electric’s GEnie sank to 20,000 lonely members after being sold for the second time in eight months. Prodigy was dumped by its frustrated founders, IBM and Sears, after racking up losses estimated at $1.2 billion. Apple snipped the connection on its eWorld service. Could AOL be next?

So dire were the indicators that in August, when AOL announced that it had ended the fiscal year with more than $1 billion in revenues, nearly triple 1995’s results, no one cared. Analysts seized instead on the final quarter’s unprecedented membership churn — 2.1 million subscribers in, 1.4 million out, with 300,000 applicants rejected — and calculated that the company had spent between $210 and $240 to snare each of its 400,000 net new members, up from $135 earlier in the year. It didn’t help that the results were released two days after the 19-hour “service interruption,” a Keystone Kops episode in which engineers at one AOL facility introduced a software error while the crew at another facility had taken the system down for routine maintenance. AOL short sellers on Wall Street, of whom there’s no shortage, joked that Case had actually staged the crash himself, to distract attention from the disastrous returns. If so, it didn’t work: the company lost one-eighth of its market value the next day.

AOL’s strategy has been built on the notion that the Net would remain a cult attraction, unsuited to a mass market that can’t handle anything more complicated than a VCR. “The Web needs to be easier, not harder,” says Case, sliding in his chair like a restless teenager.

AOL’s collapsing stock — from a high of $71 a share in early May to $26 and falling in early October — should by rights have left it hamstrung. For two years Case relied on hosannas from Wall Street to finance a string of expensive if not necessarily profitable acquisitions — $41 million for BookLink Technologies, the Massachusetts company responsible for AOL’s third-rate Web browser; $35 million for Advanced Network & Services, a Michigan-based engineering firm that helped build the backbone of the Internet; $31 million for Medior Inc., the California outfit that designed the interface for Time Warner’s ill-starred interactive television trials in Orlando, Florida; $11 million for California-based Global Network Navigator, a stand-alone ISP originally envisaged as AOL’s Internet flagship; $15 million for AT&T’s ImagiNation Network, an online game operation with 100,000 subscribers and ambitious plans for a multiplayer service called CyberPark. The surging stock had also let Case augment meager salaries — some AOL executives get half the paycheck they could expect elsewhere — with fat option packages. But the company hasn’t exactly gone into retrenchment mode.

AOL has débuted nearly 150 new sites since June, from PlanetOut to The Knot; from Thrive, a partnership with Time Inc. aimed at the health-and-fitness set, to the AOL Banking Center, a joint venture with Intuit, Bank of America, and 17 other banks. It revamped its ad program to conform to Madison Avenue’s expectations and enlisted the Nielsen folks to provide credibility. AOL Europe has been launched in a joint venture with Bertelsmann, the German media conglomerate, and AOL Japan is in the works for next spring, in partnership with Nikkei and Mitsui. AOL is pouring $300 million into the drive to reach 10 million members and double its annual revenue to $2 billion. And a mammoth crane towers over the sprawling new headquarters, which are being expanded even as employees move in. Either Case knows something Wall Street doesn’t, or he’s in deep denial. Or both.

“I just think there is confusion in the marketplace,” he says calmly, reprising a standard CEO line. “We try to communicate our point of view, but at the end of the day we have to meet the needs of Main Street rather than the short-term needs of Wall Street. We’re willing to take the long-term view. We believe this is a scale business. So we’re still in a mode of gunning for growth.”

Keyword: brand

Case may be wearing blue jeans and running shoes, but beneath the nice-guy demeanor lurks a full-tilt entrepreneur. He’s not one for soul-searching; like any good marketeer, he talks fast and stays relentlessly on message. The Internet? “We’ve always viewed it more as an opportunity than a threat.” The blackout? “It made us look like a bunch of idiots — but when we started 10 years ago, not being available for a year wouldn’t have got that kind of coverage.” AOL’s biggest mistake? “Not being effective in communicating to the marketplace all the reasons AOL is superior to competitive offerings.”

Actually, brand building is Case’s greatest strength. It’s a skill he started learning when he went to work at Procter & Gamble after graduating from Williams College in 1980. He spent two years in Cincinnati pushing P&G hair-care products — Lilt home permanents, Abound hair-conditioning towelettes — then left for Pizza Hut, where he was put in charge of new pizza development. Sent on the road in quest of new ideas for toppings, he bought a Kaypro and went online — an experience he found so compelling that two years later he was running Quantum Computer Services, an online service for Commodore 64 computer owners that eventually morphed into AOL.

Leonsis came aboard in 1994 after AOL laid out $35 million in stock to buy his Florida-based new-media ad-and-marketing company, Redgate Communications, which specialized in interactive shopping. He brought a certain amount of media savvy to the mix, not to mention a great deal of chutzpah.

Case and Leonsis are the odd couple of cyberspace — “the monk and the clown,” as one analyst calls them. If Case would prefer to run the company by email, as some have suggested, then Leonsis is always out there performing. “He’s Silicon Valley’s answer to the car salesman,” says author and information consultant Richard Saul Wurman approvingly. And Case? As Leonsis puts it, glancing all around: “Steve is in the air.”

This is the duo that William Razzouk, a straitlaced, 48-year-old sales-and-marketing executive who left the Number Two job at Federal Express to become AOL’s president in February, was supposed to complement. Razzouk’s arrival was part of a game plan set in motion by the retirement in November 1995 of AOL chair James Kimsey, a West Point graduate and onetime Washington restaurateur who founded Quantum with Case and a former Arpanet engineer named Mark Seriff. Kimsey, who oversaw financial matters but hadn’t had a hands-on role in the company for years, often said he wanted AOL to have “adult supervision” after he left — a prospect that Case was said to have found less than enthralling. Razzouk certainly qualified as a grown-up, but his buttoned-down management style was alien to a company one observer describes as “a start-up on steroids.”

AOL’s phenomenal growth — from 1 million subscribers in 1994, to 3 million in ’95, to 6 million in ’96 — has been aided by what financial managers call “aggressive” accounting. Instead of taking a balance-sheet hit on its massive subscriber-acquisition costs as they’re incurred, AOL has deferred them — at first for 12 months, then for 18, and now for two full years. Though permissible under IRS rules that allow companies to treat new subscriber costs as an investment, the practice puts AOL in the position of needing to sign up more and more new members to pay the bill for bringing in their predecessors. By June 1995, AOL had racked up some $51 million in deferred costs; by June ’96, the figure had soared to $314 million — enough to bury the fiscal year’s $30 million pretax profit.

AOL defends its accounting practices vigorously: “That’s what media companies do,” Leonsis says. “Wired does it.” Actually, Wired doesn’t, nor do most mainstream publishers. Yet the question isn’t whether AOL is entitled to defer the costs, but whether, as skeptics charge, the practice papers over more serious problems. “If you look at this company using more conservative accounting, you see a company that appears very sick,” charges Financial Shenanigans author Howard Schilit. He’s not alone.

One person who seemed to share that view was Bill Razzouk. Even as Case was appearing on the cover of BusinessWeek in a sea of floppies, Razzouk was signaling to the financial community that AOL intended to stay the onslaught and focus on improving customer service, reducing churn, and tightening management. “Razzouk saying ‘We’re not going to air-drop disks for a few months’ was akin to heresy,” says one industry analyst. “What this guy was for them was a stick up their butt.”

Doomsayers call AOL a house of cards. But the lunge for hypergrowth may well be the right choice — perhaps the only choice.

AOL’s pedal-to-the-metal strategy predated Leonsis’s arrival, but he picked it up and ran with it. At least one analyst — Gene DeRose of Jupiter Communications — maintains that Leonsis finally said it was either him or Razzouk. Not so, says Leonsis: “It was between Steve and Bill. Steve brought him in, Steve worked with him closely, and Steve just didn’t feel that comfortable.” Case insists that Razzouk, who’d already bought a house in the Washington area, simply became unhappy about relocating his family from Memphis — an explanation he offers without apparent embarrassment. Razzouk — who’s since taken a job heading a new unit of the Philadelphia-based financial services company Advanta, and whom AOL ended up paying nearly $3 million in salary and options for four months of work — hasn’t commented.

With Razzouk gone, AOL’s brief flirtation with caution ended. The new marketing onslaught means AOL won’t, at least for the moment, have to worry about how to repay the deferred costs, because cash from new subscribers will be pouring in. What remains to be seen is whether the new subscribers will stick around long enough to recoup the cost of bringing them in. And whether the price war being waged by AOL’s flat-fee competitors will stop before the revenue from subscribers sinks below the cost of providing service. But no one at Dulles is waiting around for answers. “We’re gearing to get the rest of the world online,” AOL VP Katherine Borsecnik says brightly. “The 89 percent that’s not there yet — that’s the AOL mantra.”

While the Street is full of doomsayers who regard AOL’s financial structure as a house of cards, the lunge for hypergrowth may well be the right choice — perhaps the only choice. Certainly Case shows no doubts. “It seems to us that there will be a handful of major global players,” he says, ticking off the advantages of bigness: not just economies of scale, but the buying power to acquire programming and technology to make your service attractive to yet more people, which in turn provides the muscle to generate new revenue streams from online transactions and advertising. “The big will get bigger and the small will get marginalized,” says Leonsis. “This isn’t going to be a business where 380,000 Web sites are going to be important.”

The question is, Can Case and Leonsis pull it off?

Keyword: morph

The prospects are daunting. According to a recent Yankelovich Partners survey, online services and Internet usage combined grew 100 percent from mid-1994 to mid-1995 but only 50 percent from mid-1995 to mid-1996 — a pattern that suggests the wave AOL has ridden may not last. Another study, by the San Francisco market-research firm Odyssey, found that nearly half the households connected to the Net now use an ISP, while only 35 percent use an online service such as AOL; six months earlier, the figures were reversed. Churn, churn, churn. “AOL brings them in, trains them, and they go off,” says RELease 1.0 publisher Esther Dyson. “How do you keep them? By creating compelling content.”

Enter Brandon Tartikoff — I’m sorry, Ted Leonsis.

When he arrived at AOL in August 1994, Leonsis found it pretty boring: “It was The New York Times repurposed. It was NBC press kits.” Big brands, but so what? Then David Gardner, a former Louis Ruykeser’s Wall Street writer who’d started his own investment newsletter with his grad student brother Tom, went online with The Motley Fool; in 30 days it shot past Morningstar and Worth OnLine to become AOL’s most popular personal-finance site, pulling in 40,000 visitors a day. Then, Brian Henley, a junior executive Leonsis had played golf with in Florida, came up with an idea for a golf site — which led Leonsis to the realization that there must be hundreds of young folks out there to whom the idea of launching an interactive service was as natural as starting a magazine had been to Rolling Stone founder Jann Wenner.

Meanwhile, with a million members, AOL was zooming past Prodigy, catching up to CompuServe, and sweating the summer 1995 arrival of The Microsoft Network, which everyone expected to sweep the field. It didn’t happen. “I always thought they had a secret plan,” says Case, who’d urged the Justice Department to investigate Microsoft’s bundling of MSN and Windows 95 on antitrust grounds. “I thought that what they were beta testing had to be different from what they were going to launch, because what they were beta testing was not very good.” Last December, a month after AOL tallied its 4 millionth member, Microsoft announced it was recasting MSN as a gateway to the Internet.

These days, Leonsis is fond of saying his real competition isn’t Microsoft, it’s Seinfeld. It’s also spouses, children, pets — anything that keeps you from logging on during the prime 7-to-11 time period. “Last night was a good example,” he explains. “I worked late, went home at 8:30, had supper, spent some time with my kids, talked to my wife, took a shower, and now it was 10 o’clock and I had three choices — I could read USA Today or The Wall Street Journal, I could watch television, or I could get online.” Sadly, Leonsis was tired; television won out. But that’s the scenario he envisions in millions of homes across the country.

But to beat Seinfeld, as ABC and CBS have discovered, you need something pretty compelling. Coming up with likely candidates is the job of AOL’s Greenhouse, the incubator program set up shortly after Leonsis arrived. In exchange for promotional guarantees and up to $500,000 in seed money, AOL typically gets 20 percent of the new company and the rights to its programming for two to three years; AOL then pays royalties based on the amount of time its subscribers spend on the site, while the start-up gives AOL a cut of its ad revenues and transaction fees. “It’s a win-win situation,” says Danny Krifcher, the 34-year-old Harvard MBA who heads the Greenhouse. “Our members get original programming, these companies get launched, and our equity appreciates.”

The channel concept is “Ted’s vision” — but some channels are even harder to pick through than cable TV listings.

“We call AOL the mothership,” says Tom Rielly, the 32-year-old head of PlanetOut, which launched on AOL in September. The founder of Digital Queers, a San Francisco nonprofit devoted to bringing gay and lesbian organizations into the computer age, Rielly set up PlanetOut on The Microsoft Network last year, then moved it to AOL and the Web with Greenhouse seed money and venture financing. Now he’s hoping to create “a home” for gay people on AOL’s Life Styles & Interests Channel, which he shares with such disparate groups as American Woodworker, Quilting Forum, Christianity Online, and ParaScope, the folks who offer you the latest on UFOs, black helicopters, and the CIA’s latest secret ops.

“We think it’s a big world,” says Krifcher. “We’re here to serve all the communities that are out there.”

The Greenhouse has brought in some of the service’s most popular shows, from Extreme Fans, a site for sports addicts, to Hecklers Online, which offers “themed chat” like HO-SPAN and HOprah, as well as a Giggle Box with member-supplied jokes on everything from nuns to homosexuals to your sister (“What’s the difference between your sister and a Cadillac? Most guys haven’t been in a Cadillac”). There’s Moms Online, which features a Kid of the Day (“Click here to find out more about me”) and the Daily Alexander, an ongoing chronicle of the author’s 2-year-old son. There’s Parent Soup, which combines a General Store where you can buy potty-training products with a What Would You Do? column (“He had a vasectomy but I found a condom in his laundry”) that allows you-the-user to give free advice. But eclectic as it is, the Greenhouse accounts for only about 40 sites — a small part of Leonsis’s programming efforts.

A much bigger chunk of AOL’s resources is going into joint ventures with established media companies. Time magazine defected to CompuServe last year after being offered a $3.5 million guarantee (compared with $1 million from AOL). But AOL Productions subsequently hooked up with Time Inc. to create Thrive, an interactive health/fitness/food/sex service that resides jointly on AOL and Pathfinder. The Style Channel, AOL’s joint venture with Disney’s Fairchild Publications, offers everything from fashion tips and celebrity gossip to an online makeover. New Line Cinema — producers of Dumb & Dumber and the Nightmare on Elm Street series — collaborated on The Hub, a teen channel devoted to G-rated pinups and beefcake (“Download This Guy!”) plus message boards like Sex Talk with Dr. Judy, Konspiracy Korner, and Ken’s Guide to the Bible.

Seinfeld may be safe for another month or two, but Leonsis claims that with 1.8 million users clocking in over the four-hour prime-time period, AOL is almost even with MTV and closing in on Larry King. On the other hand, the average AOL user spends only 13 minutes a day online. And while MTV can pull a million pairs of eyeballs to a single image, AOL’s users are divided among countless sites and subsites. “People find three or four things they love and they keep coming back,” says Krifcher. “Our challenge is to develop those three or four things for lots and lots of people. It’s all about building great new brands in cyberspace.”

Keywords: context, community, commercialization

One of the more curious things about AOL’s brands is that most of them are as readily available on the Web as on AOL itself. Case says that AOL’s version of The Motley Fool, for instance, “is dramatically superior to The Motley Fool on the Web.” The numbers bear him out: fully two-thirds of the Fool’s 40,000 daily visitors come in on AOL. “Most of that is because they have a well-developed community on AOL,” says Case. “And this is not just about content — it’s also about context and community.”

Content, context, and community top the list of C-words Case likes to cite in summing up AOL’s appeal. Context covers everything from AOL’s onscreen look — the bright colors and fuzzy-wuzzy icons that render it both saccharine and bland, the electronic equivalent of Disney’s Quasi doll — to its complex organizational matrix. “If you want travel information and you search the Web, you get a huge amount of information with no quality or relevance ranking,” says Borsecnik, who oversees what’s known as “brand management” for AOL’s programming. “But we know what our demographics are” — primary subscribers tend to be male (69 percent), middle-aged (median age 42), college educated (37 percent), and family-oriented (68 percent married, 46 percent with children) — “so we can provide access to resources that meet the needs of our members.”

Borsecnik programs everything from content channels to the welcome screens that greet users when they sign on. The latter change every 15 minutes, and vary by area code and even ZIP code: in suburban Virginia at midafternoon, when users tend to be schoolkids, housewives, retirees, and investors, the screen features Highlights magazine, The Motley Fool, and ABC’s Soapline Daily; at midmorning in Manhattan, it offers Omaha Steaks, The New York Times online, and a money-and-career site called About Work. Borsecnik is currently restructuring the Travel and Sports channels along the lines of Kids Only, which recently shifted from listing its offerings by provider (ABC, Marvel Comics, Nickelodeon) to grouping them into categories (Games, Clubs, Sports, Homework Help). Since the overhaul, she says, Kids Only has been drawing more users and keeping them longer, accounting for nearly a half million hours of connect time a month.

The channel concept was, as Borsecnik puts it, “Ted’s vision,” based on the television metaphor and the idea that programs would get canceled. The most visited channel is People Connection, AOL’s chat and live events domain, which has been around since the service was started in 1985. Today’s News, which 54 percent of AOL members say they look at regularly, is almost as popular, followed by Computers & Software (42 percent) and Travel (37 percent). And though there’s an Internet Connection channel for the 37 percent who wish to boldly go et cetera, Web pages are so casually interspersed among AOL’s own content offerings that some users might not even notice when they’ve wandered out of the safety of the mall. “We think people are more interested in sports and investing and sending email than in whether their content is stored in AOL’s RainMan format or in HTML,” says Case.

Despite Borsecnik’s efforts, however, some channels are even harder to pick your way through than a typical newspaper’s cable TV listings. “There are a lot of navigational issues,” she concedes. No kidding: neither the Families Channel nor the Romance Channel appears on the Main Menu, while others that are more popular — Education, Travel, Personal Finance — get their own click bars. The clutter is so extreme that some of AOL’s outside content providers are scrambling to come up with names that will put them at the top of their channel’s list boxes, the way locksmiths and towing companies name themselves AAAAAA to get to the front of the phone book. And installing the software, though it may be a no-brainer for the computer-adept, can present a challenge to the less fortunate. “We’re still having problems in our observation labs getting my mother signed up,” Borsecnik admits.

Online chat can be a party, or it can be “like being in a cave with a bunch of people you can’t see.”

But for the moment, AOL does have one major advantage over the Web. “Chat is the big difference,” observes Brian Henley, the 32-year-old entrepreneur behind iGolf, which gets 8,000 to 10,000 visitors a day on AOL and about the same number on the Internet. The problem is partly technical — Web-based chat systems still need work. “Interactivity on the Web is difficult. And on the Web, you get a lot of people who are just cruising. On AOL, there are people who hang out at iGolf every night of the week. A lot of them go right into the chat room. And you get more feedback than you could ever want, whether you solicit it or not.”

“When you look at the Web,” says Leonsis, “it’s people to content to content — you browse, you hyperlink. When you look at AOL, it’s people to content to people. On the Web it’s pages, it’s more like a magazine; here it’s more like a party.”

It can be a party, or it can be, as Paul Saffo of the Institute for the Future puts it, “like being in a cave with a bunch of people you can’t see.” Either way, the people-to-people idea has been crucial to AOL from the beginning. Case first went online after reading Alvin Toffler’s description in The Third Wave of the electronic communities on The Source, a pioneering computer network founded by an eccentric entrepreneur named William von Meister. It was The Source’s email and online forums that enticed Case to northern Virginia to join von Meister’s Control Video Corporation, an ill-fated venture to deliver Atari videogames online. Control Video crashed along with Atari, but it provided the springboard from which Case and CEO Jim Kimsey founded Quantum, which became America Online in 1991. “From day one, we thought the people aspect was central to this,” Case says, “and really the soul of the medium.”

With chat, the medium also turns out to be highly profitable. Teens on The Hub, preteens on Kids Only, lonelyhearts on Romance Connection, animal lovers on Pet Care Forum, the proverbial little guy on The Motley Fool — whatever your trip, AOL has a 900 number for you. The company’s oft-maligned rules governing online behavior have at least created an environment that makes parents feel secure about their kids going online. And if you don’t like supervision, it’s easy to create private chat rooms, where anything goes. At a Jupiter Communications conference last year, one AOL vice president said, “Our joke is, the only reason we have content on AOL is so that people have something to talk about.” It’s no joke: email may be AOL’s most popular feature, used by 86 percent of its members, but chat is its most lucrative, accounting for a quarter of the 40 million hours of monthly connect time —billable at $2.95 each.

Chat fiends with three-figure monthly bills help explain why one-third of AOL’s customers have historically accounted for an estimated two-thirds of the company’s revenues. And that, in turn, explains why the stock began its downward spiral last spring when AOL, in a move to fend off price-chopping competitors, announced a new “volume” plan of 20 hours for $19.95 — barely a third of what the company collected for the same amount of time under the old pricing scheme.

The pressure from flat-fee ISPs explains another C on Case’s list: commerce. There was a time when AOL bragged of having “no annoying advertising” — but that was then. With 90 percent of its income coming from subscription fees, AOL has to broaden its revenue stream to survive. The goal now is to get a third from transactions and advertising, which potentially offer far higher profit margins.

Case doesn’t think users will mind: “If you’d asked us three years ago what the last bastion of commercial-free interactivity would be, it would have been the Internet. But there’s been rapid commercialization of the Web, and there are far more ads on it in far more intrusive ways than anything on AOL.”

But Case’s the-Web-did-it-first argument ignores the relentless commercialism of America Online — the cheesy pop-ups when you log on hawking this or that book or videocassette or CD-ROM, the exclamatory entreaties to explore this or that content area, the pleas to spend more time when you’re trying to sign off. And while the Web is sprouting billboards to grab people’s attention as they cruise, consumerism is built into the very architecture of the AOL cybermall.

The trick is to convince advertisers they’re better off providing value on AOL than on the Web.

The problem is that advertisers understand billboards, while the cybermall is something Madison Avenue is still struggling to comprehend. AOL got a few flashy buys when it started taking ads two years ago — McDonald’s created a games-and-promo site called McFamily; General Motors sponsored an Oldsmobile Celebrity Circle, which used chat-with-the-stars as a come-on for product info. But on the whole, the effort failed dismally, largely because it tried to force advertisers into a “ghetto” in the Marketplace section. “It was a doomed program from the start,” says Roland Sharette, interactive director at J. Walter Thompson.

Last June — on the day Razzouk resigned, as it happened — AOL rolled out a new approach that more closely resembles the Web model. Now you can buy buttons or banners (“the plankton of the interactive food chain,” in the words of AOL’s advertising VP, Myer Berlow), you can sponsor areas created by AOL, or you can create custom areas as American Express has done. Berlow says that in the first 45 days of the new program, AOL sold $25 million in ads — up from $8 million the year before — to companies like AT&T, Sprint, Starbucks, Broderbund, and Reebok.

The deals AOL is most excited about — the one with Reebok, for instance — are patterned on its arrangement with American Express. On AmEx’s ExpressNet you can apply for cards, check your accounts, go shopping, consult three different travel guides, read Zagat hotel and restaurant surveys, search Travel & Leisure online, download maps, check out message boards, and get special promo offers. “When you go into the AmEx area,” Leonsis cries excitedly, “it’s, What is this? Is this content? Transactions? Customer support? Advertising? And the answer is, Yes!” He beams. “These are new-media life forms.”

They’re also AOL’s model for the future. “The breaking-and-entering model of advertising that worked on television — ‘I’ll jump into your home and scream at you!’ — doesn’t work in cyberspace,” says Berlow, who joined AOL after 20 years in the ad business in New York and Los Angeles. “People have a choice of whether or not they’re going to invite you in, so advertising has to provide value.” The trick is to convince advertisers they’re better off providing value on AOL than on the Web. Not only does AOL offer more consistent traffic than the Web and more precise usage data, it also has the ability to let advertisers identify and communicate directly with members who click on their message, something that’s harder, at least for now, to do on the Web. But in the 18 months that AOL stubbornly clung to its old ad program, a Web buy and a Web address became must-haves for big-time advertisers.

Berlow has talked to any number of companies that are stuck on having their own Web site, and his response is always the same: “If you build it, they won’t come.” It’s a good line — as far as it goes. “I understand what he’s saying,” says JWT’s Sharette. “But if you don’t build it, you’re certainly not going to be part of the 21st century.”

Keyword: underdog

So, Madison Avenue wants to wait and see. The Street has Case and Leonsis by the shorthairs. Webheads think they’re history. But these guys have been a long shot from the start. “Every time somebody gets ready to lower Steve Case into the grave,” says Tom Rielly of PlanetOut, “they get to the cemetery and discover that he’s built a high-rise on top of it.”

In September, America Online, the 6 million-member underdog, held a pep rally for its 1,500 northern Virginia employees at a convention center not far from the Dulles headquarters. There were roller dancers and satellite hookups, theme songs and a cheering crowd. Case made his entrance in jeans, sunglasses, and a black leather jacket, addressing the troops through a headset mike. Leonsis came out and cried, “We can be like Coca-Cola! We can become like Disney, like Nike, like MTV!” David is Goliath.

The occasion was the $300 million marketing blitz intended to “relaunch” AOL. This time AOL has gone way beyond free disks: it’s mailing videos to existing members telling them how great AOL is. It’s got two semis touring the country in an online roadshow. It’s got Chiat/Day, the folks who brought you Apple’s 1984 Super Bowl spot for Macintosh, to do a TV campaign featuring the theme song from The Jetsons and the tag line, “The Future — Now Available on America Online.” It’s even bought airtime on Seinfeld.

Steve Case has built a vast enterprise around his formative online experience — the frustration of trying to link his Kaypro to The Source in 1982 and not being able to get it to work. Combining entrepreneurial zeal with an innate ability to plumb the lowest common denominator, he’s made it his mission to hook everybody else up with him, and to do it as painlessly as possible. This gives AOL a worldview that’s completely at odds with the Net-centric perspective. In the AOL view of the world, the Internet is not a boundless wonderland; it’s content to be packaged and arranged on the shelf. In the AOL view, what’s paramount isn’t freedom but responsibility, so that kids and families can travel cyberspace in safety. In the AOL view, naysayers on Wall Street and Madison Avenue, in the computer industry and elsewhere are as wrong about the mass market — and AOL’s ability to tap it — as they have been in the past.

Leonsis recites the litany. “Everybody said interactive television — broadband and cable — is going to put you out of business. Then Microsoft announced it was launching MSN, and that was going to kill us.” He all but yawns. Broadband and cable are indeed on the horizon, but most computer owners are still on 14.4 modems — if they’re online at all. And Microsoft has cut a deal — one that puts AOL on the Windows 95 desktop and makes Microsoft’s Internet Explorer the default browser on AOL. Still, AOL execs are not so naïve as to think they’ve checkmated Microsoft: “We fully expect them to be back,” says David Gang, marketing vice president.

What Leonsis doesn’t say is this: AOL as we know it is really just a distribution platform, like the Web or CD-ROM.

December 1, 1996

December 1, 1996