April 4, 2013

What’s a book, anyway? The answer used to be simple: two covers, a lot of words in between, printed on paper and meant to be stored on shelves. Not any more. With ebooks the paper is gone, the covers are vestigial, the shelves are virtual, and the words might be joined by playable videos, expandable photos, interactive graphics, and HTML5 pyrotechnics. The question is not what a book is but what it can be.

So it was gratifying to spend a couple of days recently with people who have smart ideas about this. With The Art of Immersion just published in Italian, I was invited to Europe to speak at IfBookThen, a future-of-books conference staged in Milan by the Italian e-publisher BookRepublic and reprised two days later in Stockholm by Publit, its Swedish counterpart. Here’s what I came away with.

1. Books are data.

As trade journalist Edward Nowatka pointed out, Amazon’s Kindle is essentially a data-collection device—one that tracks your bookmarks, highlights, notes, and annotations, not to mention the last page you read. Because they go through third-party retailers, most publishers don’t have access to anything resembling this kind of information. But what if they did? Nick Sidwell of Guardian Books made a convincing case for using it to inform decisions about what gets published.

Unlike most publishers, Guardian Books has a direct view of readers through its affiliation with the Guardian newspaper, which sells 215,000 copies a day and gets 30 million unique Web visitors per month, as well as the Guardian Bookshop, which carries more than 180,000 titles online. They use this data to help decide what subjects to cover and how, how big the readership might be, and how to reach them. But the editor remains central, Nick maintained: “We don’t let data dictate what we’re doing—we use it to inform what we’re doing.”

The example he used was Facts Are Sacred, a brief compendium of big-data revelations culled from the paper’s data blog. The blog has approximately 1 million monthly readers, 10 per cent of whom are considered “engaged users”—enough to make it a fairly obvious candidate for bookdom. Not that they could expect to sell 100,000 copies: Fewer than a quarter of those engaged users have e-readers, and fewer still live in the UK or the US. A couple of other calculations left them with a niche market that was considerably smaller—but they managed to sell the title to 70 per cent of the people in that market before the book was pulled for updating. Not bad for an industry in which sales projections are traditionally based on guesswork.

2. Books are tech.

Literature has always been dependent on technology, but for most of the past 160 years the technology has been so stable that we ceased to think of it as tech at all. No more. One speaker focused on new possibilities was The Literary Platform‘s Joanna Ellis, who as marketing director at Faber and Faber was involved with such projects as Malcolm Tucker: The Missing Phone, a smartphone app tied to a book that was spun off from The Thick of It, the BBC’s devilishly funny sendup of UK politics. Molly Barton, global digital director of Penguin, talked about working with startups like Citia, a New York company that’s made app versions of such books as Kevin Kelly’s What Technology Wants and Dan Ariely’s Predictably Irrational. Created in HTML5 and designed primarily for the iPad, Citia’s apps present a stripped-down version of the book in a dazzlingly kinetic, hypercard-like presentation that’s about as far from the traditional page-turning format—whether on paper or on a Kindle—as you can imagine.

Meanwhile, Penguin’s Dorling Kindersley arm has partnered with Inkling, a San Francisco startup that likewise offers possibilities far beyond the range of a Kindle. Founded by Matt MacInnis, a former Apple education exec, Inkling began with the idea of reimagining the textbook. Two months ago it launched Habitat, a software platform that allows publishers of any sort to create interactive, multimedia ebooks without the expense of creating a custom app. Inkling titles are searchable on Google; they can also be bought through Google, as well as through Inkling’s online store.

Pearson, Penguin’s parent company, is an investor, along with McGraw-Hill and Sequoia Capital. In general, however, Molly believes that publishers are too focused on the major players—Apple, Amazon, Google—to pay enough attention to entrepreneurs who are actually trying to rethink books. Startups, for their part, tend to be a bit clueless about how the publishing industry works. If they could figure out in advance whether their offering would be relevant to a company’s product people, marketing, or sales, they could save themselves the frustration of being passed around from person to person within the organization.

3. Books are links.

And links are money. Ricky Wong, an ex-Google engineer who’s founded a fledgling outfit called Mobnotate, presented an idea for connecting ebooks via hyperlinks. A Mobnotate algorithm generates links to relevant books—links that can appear within other books, or (as in this example from the news analysis site Fair Observer) at the end of a post online. Either way, they’ll take readers direct to the book’s page on an ecommerce site such as Amazon. Effectively, then, these links provide a way for publishers to advertise other titles from their catalog that readers might be interested in; Mobnotate makes money by taking a cut of any sales.

4. Books are not books.

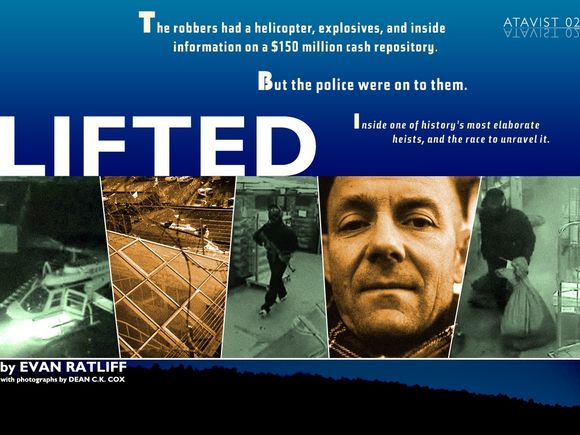

And then there was Evan Ratliff, a longtime Wired colleague who’s co-founder and CEO of Atavist, a Brooklyn startup that’s moved beyond the whole idea of books. “We think of ourselves as a storytelling company,” Evan said. “We don’t think of ourselves as a company that makes books.” So forget “enhanced.” Instead of trying to retrofit books so they’ll work on the Web or on digital tablets, the idea is to figure out how best to tell stories today.

That means certain notions have to go. Length, for starters: Atavist publishes nonfiction stories that are somewhere between magazine and book length—long enough to be satisfying, short enough not to require a major commitment. And secondly, preconceived notions of how to tell a story. For his own first Atavist story, about a brazen heist in Sweden, Evan provided a “preface” made up of surveillance video that captured the robbers as they swooped in by helicopter and descended on their target with AK-47s. It’s almost as suspenseful as the opening of The Dark Knight.

Atavist made news last fall when it announced a multi-million-dollar partnership with Barry Diller and Scott Rudin to create a new publisher called Brightline that will, as Diller put it at the time, “start with a blank piece of paper.” Old metaphors die hard—but enough of the kind of thinking that prevailed at IfBookThen and metaphors will be all that remain.

Comments

Comments are closed here.