This is the first in a series of three essays for the Milken Institute Review about digital media, scarcity and competition. See also “The Blockbuster Syndrome” (cover story, July 2014 issue) and “The Attention Economy 3.0” (cover story, July 2015).

CONTRARY TO POPULAR BELIEF, the 20th century did not end at the same time for everyone.

CONTRARY TO POPULAR BELIEF, the 20th century did not end at the same time for everyone.

For those in the music business, it sputtered to a halt with the close of 1999—the year U.S. recorded-music sales reached their all-time high of $14 billion; by 2012, they had dropped to half that. For newspapers, the end of the century arrived a year later, when U.S. ad revenues hit nearly $49 billion; now they’re down to a mere $22 billion. Hollywood was able to stave off the century’s demise until 2002, when box-office admissions in the United States and Canada peaked at 1.6 billion; last year they were down 15 per cent from that (which is not bad, considering). Magazines, for their part, seemed to lead a charmed life—through 2006, anyway, when ad pages topped out at 253,000; since then, they have dropped by more than a third. As for television, the major broadcast networks have been on a slow, inexorable slide into the future for decades. In 1980, according to Nielsen, well over half the TV sets in America were tuned in to ABC, NBC or CBS during prime time. By 2012, even with the addition of Fox, that number was a little above 20 per cent.

As the industrial age gives way to the digital, we are rapidly moving from a period of mass production, mass consumption, and (at its height in the 1950s) mass conformity to an era of networked production, unbundled consumption, and personalization of just about everything. Yet in the media industries in particular, this transition is even now the subject of widespread confusion and denial. In their determination to stave off the demise of long-profitable 20th-century business models, media companies of every stripe have largely behaved as if they were sheltered from Joseph Schumpeter’s “perennial gale of creative destruction.”

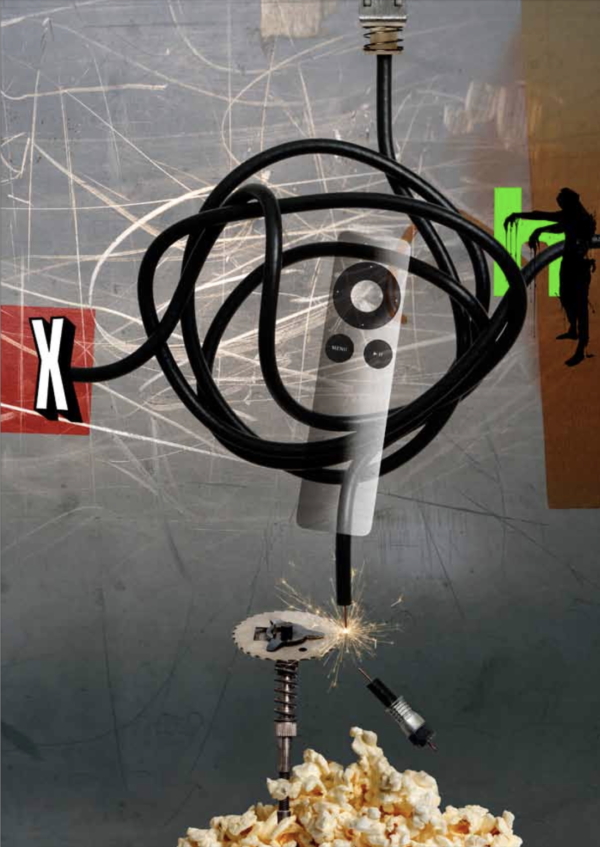

The next industry to be ushered headlong into the 21st century will most likely be cable. Companies including Comcast and Time Warner Cable continue to shrug off the threat of “cord-cutting”—subscribers dumping their expensive pay-TV packages in favor of streaming Internet services like Netflix and Apple TV. True, the numbers don’t look terribly threatening at the moment: After years of talk and speculation, only 5 per cent of U.S. households have made the move. Just this past spring, Nielsen down-played the phenomenon, calling it one of several “interesting consumer behaviors that we want to keep an eye on.”

No cause for alarm, apparently. But just a few weeks later, Nielsen reported that for the first time ever, cable companies lost more subscribers—80,000 over the 12-month period ending in March—than they gained. “Cord-cutting used to be an urban myth,” cable industry analyst Craig Moffett declared in a research report in August. “It isn’t anymore.”

Schumpeter’s insights were overshadowed in their time (the 1930s and ’40s) by the paramount specters of depression, totalitarianism and war. Today, his analysis of the role played by innovation and entrepreneurship in sweeping away the past seems prescient. Yet as the cord-cutting example suggests, technology itself is only one factor in Schumpeter’s gale. An even more powerful factor is audience behavior, which is influenced but hardly determined by the available technology—and which in turn has a bearing on a welter of other variables, from means of distribution to modes of storytelling.

It’s not enough to keep up with technological change, though that in itself can seem overwhelming. Media companies need to evaluate their business strategies against a complex interplay of technological innovation, audience expectations and behavior, evolving entertainment forms, and long-term cultural trends. The problem is that in the midst of the storm, many of these companies have become too insular to comprehend the forces of destruction they are prey to—much less know how to respond.

A Revolution in Expectations

Let’s start with the long-term cultural trends, since of all the forces at work, these are the most fundamental. Societies tend to resemble the technologies that define them. Industrial societies typically organize themselves one way, post-industrial digital societies quite another. Industrial production depends on large numbers of people taking orders from the top as they engage in repetitive tasks that yield only a small portion of the whole. Nearly everyone is a cog in the machine. Industrial-age companies—including newspaper publishers, movie studios, and television networks—tend to operate accordingly, on a command-and-control model that relies on hierarchical thinking and strict categorization. Not for nothing was Hollywood once dubbed “the dream factory.”

Let’s start with the long-term cultural trends, since of all the forces at work, these are the most fundamental. Societies tend to resemble the technologies that define them. Industrial societies typically organize themselves one way, post-industrial digital societies quite another. Industrial production depends on large numbers of people taking orders from the top as they engage in repetitive tasks that yield only a small portion of the whole. Nearly everyone is a cog in the machine. Industrial-age companies—including newspaper publishers, movie studios, and television networks—tend to operate accordingly, on a command-and-control model that relies on hierarchical thinking and strict categorization. Not for nothing was Hollywood once dubbed “the dream factory.”

Lines are drawn between author and audience, entertainment and advertising (or “church” and “state,” in the case of journalism), fiction and reality. Sometimes these distinctions are less than sacrosanct: We’ve had product placements in movies and TV shows for decades—but let one be too obvious and it will immediately be castigated as “blatant,” even in the ad industry trade press.

Digital societies are more fluid, with networked structures and a sense-and-respond mentality. In terms of organization, effective digital-age companies—Apple, for example—tend to resemble the Internet, decentralized and interconnected, while their less successful brethren, like Microsoft and Sony, remain hierarchical and disjointed. Control still exists, of course, but it’s not exercised through layers of middle management. Individual product lines are not set up as profit centers, an organizational gambit that destroys any incentive for internal cooperation. What once were hard classifications tend to blur, to the point that what seems natural, even sacred, to those on one side of the divide can appear all but incomprehensible to the other.

The United States is not at this point a digital society, but it’s fast getting there. Last winter I designed a survey with the ad agency JWT to get at people’s behavior and attitudes regarding the digital realm versus the physical. Unsurprisingly, the divide fell along generational lines: Based on their shopping, reading and listening habits, “Millennials” (people 18-34) were considerably more likely than older groups to be what we called “hard-core digital.” Yet, among those we surveyed, only seven per cent of the Millennials and four per cent of those in Generation X (35-48) fell into this category. Another 45 per cent of both age groups were what we’d call “on their way” to digital. This means that even among Millennials and Gen X, roughly half were merely dabbling with digital or were firmly anchored in the past. Among Boomers (49-67) and Silents (68+), that percentage was far higher.

Once people start to question their $100-plus monthly cable bills and realize that most of it goes for bundles of channels they don’t want, it’s all over.

Just as the future has been arriving unevenly among industries, then, it’s arriving unevenly among populations—even populations in the same age cohort. Nonetheless, people’s behaviors do fall into clear patterns. Even the least digitally inclined now use the Internet to research products they’re interested in buying; many of them also use it for playing games and paying bills. Those dabbling with digital do these things and more: They chat and send email; they share photographs; some buy books and music online; some even go there to get the news.

As we move up the digital adoption curve, these behaviors become ubiquitous and new ones come into play: listening to music, shopping for gifts—until finally, we reach the hard-core crowd and find large numbers of people reading e-books and tuning in to streaming music services like Spotify. Yet even among this group, only about two-thirds go online to watch TV shows—which explains why cable providers have been so slow to see cord-cutting as a threat. If past behavior is any guide, however, it could become a threat fairly soon.

With behaviors come expectations. Once people start to question their $100+ monthly cable bills and realize that most of it goes for bundles of channels they don’t want, it’s all over. Eight minutes of advertising out of every 30 on TV? Bring on the DVR. Unable to watch your favorite show anytime you want? Hulu can fix that—maybe. If not Hulu, Netflix. If not Netflix, then definitely The Pirate Bay, the file-sharing service that operates on the far side of the law.

The Schumpeterian gale carries many threats for established media businesses. Among them: constantly evolving technologies, any one of which could prove a dead end; a superabundance of ad inventory, which in turns leads to price collapses; the growing realization by advertisers that they can create their own media and buy less of it from existing publishers. And yet the revolution in expectations may present the greatest danger of all.

As people change their behavior, adopting technologies they like and rejecting others, they develop new habits and wants. But since the transition to digital occurs in fits and starts, and invariably more slowly than its cheerleaders anticipate, media executives long found it easy to lull themselves into a false sense of security. To an industrial-age mindset, online behavior patterns seem all but inexplicable, anyway. Denial seems plausible, even prudent. In fact, it is neither.

The Shifting Audience

Over the past few years, as more and more people have become comfortable with smartphones, tablets and services that let you buy or stream stuff online, three key expectations have emerged. Any one of these would be challenging to a 20th-century media company. Taken together, they require a total rethinking of the enterprise.

First, people are coming to expect an infinitude of choice. They want news and entertainment on their own terms. They see no reason they shouldn’t be able to watch movies or TV shows or listen to music whenever they want, wherever they happen to be, on whatever device they have with them—and with a minimum of advertising, thank you.

The first glimmerings of this trend could be detected as far back as the mid-’70s, when Sony, Matsushita and JVC (among others) introduced reasonably priced home videocassette recorders. “Time shift,” as Sony co-founder Akio Morita called it, freed viewers from the tyranny of network programming schedules. Suddenly, people could record their favorite shows and watch them any time. Digital video recorders, introduced by TiVo at the beginning of 1999 and eventually popularized by satellite and cable providers, made this even easier. By that time, however, time-shift was almost the least of it. The Internet was arousing a far more challenging set of expectations.

The media sector as it existed in the 20th century was an aberration — an accident at the intersection of economics and technology. Whether we like it or not, that accident is now being cleared by the inexorable forces of creative destruction and a new one is rising in its place.

With the growth of broadband and the arrival of streaming video services like YouTube, Hulu and Netflix, it’s no longer enough to be able to record a show for future viewing, or try to locate a particular video-on-demand offering in the impossible-to-navigate haystack of cable line-ups. Why should you have to deal with cable at all? And why should you be limited to shows that have recently been aired, or that networks make available through VOD? For that matter, why should you be limited to programs that have been aired in the United States? Why shouldn’t you be able to watch any TV show that’s ever been aired anywhere? And movies—why aren’t they released on the same day the world over? And music albums? We all live on the same planet, and we’re all interconnected, so what exactly is the problem? An intellectual property attorney could lay out in excruciating detail the tangle of rights issues and business interests that constitute the problem—but nobody wants to listen to corporate attorneys. People are here to be entertained.

Meanwhile, a second set of expectations has been developing. Humans have always wanted to somehow inhabit the stories that move them—to be spellbound, entranced, transported to another realm. Immersion is a state of altered consciousness—“not the prim suspension of disbelief,” as James Parker put it in The Atlantic, “but its joyous capsizing.” Historically we’ve managed to plunge in with whatever technology is at hand, from books to film to TV. But digital raises the possibility of immersing ourselves even further, and in entirely new ways.

Because this kind of thing often serves a marketing function, fueling engagement among committed fans and helping to bring in new ones, it’s turning up increasingly in connection with movies and TV shows. The Walking Dead, currently America’s most popular television series (a first for cable), offers a panoply of opportunities for involvement: Not just the show itself and the comic series it’s based on, plus of course the now-requisite Facebook page, but video games, mobile wireless games, online quizzes, “Webisodes” that extend the main story through online video, novelization, even a weekly talk show about the series. Other aspects of The Walking Dead saga don’t play out on screens at all. One of the more memorable events at last year’s Comic Con, the annual geekfest in San Diego, was a live “zombie escape”; the AMC network even runs a zombie training course for viewers who want to be extras. Fans of the show can explore all or none of these, as they wish.

So we have audiences expecting an infinite line-up of choices, and expecting to be able to immerse themselves in whatever type of story or entertainment they choose. But there is a third, closely related expectation as well: More and more, audiences expect some kind of active involvement. No longer passive consumers, they now want to be participants—critics, providers, and (through the act of sharing on social media) distributors of information.

The age of the couch potato—the ultimate passive media consumer, tagged and identified in a 1987 New York magazine cover story on the social lethargy of middle-aged boomers—is now a memory, and not even that for anyone under 30. Now, with a keystroke, we can send out smartphone photos of a plane crash, an earthquake or a riot; we can share an opinion about the government, the restaurant down the street, or the latest Brad Pitt movie. In the process, many of our most basic assumptions about media have been turned upside-down. In a digital society, the role of the media is not just to speak but to listen; the role of the audience is not just to listen but to speak.

The Natural Order of Things?

The problem is that people naturally tend to assume that whatever they grew up with is the way things ought to be, and most of the people running media businesses today are products of the coach-potato era. But no law of nature states that huge segments of the population shall zone out in front of the TV set for hours on end, or that people shall line up and pay money to sit quietly in a darkened theater with sticky floors and the ersatz-buttery aroma of diacetyl in the air, or that companies shall pay billions of dollars to newspaper publishers and television networks to advertise their wares.

The problem is that people naturally tend to assume that whatever they grew up with is the way things ought to be, and most of the people running media businesses today are products of the coach-potato era. But no law of nature states that huge segments of the population shall zone out in front of the TV set for hours on end, or that people shall line up and pay money to sit quietly in a darkened theater with sticky floors and the ersatz-buttery aroma of diacetyl in the air, or that companies shall pay billions of dollars to newspaper publishers and television networks to advertise their wares.

In fact, there is little that’s traditional about “traditional” media. The media sector as it existed in the 20th century was an aberration—an accident at the intersection of economics and technology. Whether we like it or not, that accident is now being cleared by the inexorable forces of creative destruction, and a new one is occurring in its place.

To see things this way requires taking the long view. Starting in the 1830s, the Industrial Revolution made it feasible for the first time to print reading matter—books, newspapers, magazines—in very large quantities at very low cost and to distribute it quickly to very large numbers of people. A few decades later, inventions by Edison and others—electrical power, the phonograph, the motion-picture camera and projector—made it possible to package music and theater in a similar fashion. All this was enormously efficient in terms of economics, and over time it spurred not only a series of very profitable businesses but a tremendous increase in cultural and political sophistication (the so-called “vast wasteland” of television notwithstanding). Even so, it came at a price.

Two factors in particular were troublesome. First, the advent of mass production made it prohibitively expensive for all but a handful of people to make themselves heard. Between 1835 and 1850, as Harvard Law professor Yochai Benkler pointed out in his book The Wealth of Networks, the capacity of printing presses went from 1,000 sheets per day to 12,000, even as the cost of launching a New York daily shot up from approximately $12,400 in today’s dollars to $2.9 million. Each subsequent advance in technology made the process more expensive, not less—a development that would be celebrated as the barrier to entry that made industrial-scale newspapering viable, and that has now been negated by the Internet.

At the same time, the rise of mass media severed the often-intimate connection that audiences had previously enjoyed with writers, orators and performers. Before, audiences had been a link in the creative process. In theaters, in music halls and even in print, they’d been engaged in a dialogue. Now they were being told to shush. So complete was the disconnect that when Richard Curtis (who went on to make Four Weddings and a Funeral and Love Actually) created the pioneering UK comedy series Blackadder in 1983, he was reduced to peering into basement windows around London to see if anyone was watching his show.

Yet the idea that audiences should find their voices again has not been greeted with huzzahs from the mass-media establishment. Newspaper editors in particular have been aghast at the threat to their long-standing monopoly on information. Not that they put it that way, of course — to them, it’s a question of professionalism. Bloggers, untrained and unedited, just don’t cut it; never mind that some bloggers are, in fact, far more expert in the fields they cover than the average reporter. “If I need my appendix out, I’m not going to go to a citizen surgeon,” Bill Keller, then executive editor of The New York Times, declared in a speech three years ago.

Keller eventually moderated his attacks on “citizen journalism,” admitting that tweets from Tahrir Square, for instance, shed light on what was going on during the demonstrations against Hosni Mubarak. But his mistake all along was to paint the issue as an either/or situation. Readers aren’t journalists—but like audiences of every sort today, they do expect to have a dialogue with the professionals who tell them things. And journalists should recognize that this kind of partnership works to their benefit.

Journalists can’t be everywhere and know everything. They need the help of people on the scene, people with special knowledge. In another context, these people would be called “sources.” It’s just that now, thanks to social media, the number of potential sources is almost infinite.

Give People What They Want?

As goes newsgathering, so goes the media industries in general. Audiences are coming to expect involvement, immersion and infinite choice. Some interesting experiments have resulted, especially with regard to immersion. But in too many cases, media companies have been loathe to give their customers what they want—especially when it interferes with their more immediate goal of maintaining long-profitable business models that are becoming increasingly obsolete.

A case in point is Hulu, the Web video site founded in 2007 as a partnership between News Corp. and NBC Universal. The idea was to port TV to the Internet. Tech bloggers all but hooted with derision, and with some justification: Similar efforts by music labels a few years earlier had been almost comically inept, with online stores limited to the output of a single conglomerate and selling music that came so crippled with restrictions, both legal and technological, as to be all but unusable. But this time around, the two media companies made a smart move: They hired an Amazon executive named Jason Kilar as CEO, and they backed him on two important decisions. First, he insisted on including rival networks in the site’s search results on the grounds that to do otherwise would render it as useless as those early one-company music shops. And second, he asked for every show they could possibly license on the grounds that to hold them back would be to invite piracy.

To television executives schooled in the economics of scarcity, Kilar’s moves were heresy. Scarcity has been extremely kind to TV and movie producers over the years, enabling them to limit access to their properties by funneling them into a series of highly lucrative distribution windows—theatrical, hotel pay-per-view, DVD, VOD, pay TV, free TV, and so forth. But in an age of endlessly replicable digital content, the old rules no longer applied. Enforced scarcity schemes were becoming particularly untenable, so Kilar aimed to bypass them.

Within months of its launch, Hulu’s breadth of choice, together with its ease of use and clutter-free environment, made it one of the top 10 video sites in the United States. Within a year, it was number two behind YouTube. The bloggers apologized. Hulu was a winner.

Or so it seemed. But things started to go wrong for Hulu when its top in-house proponent, News Corp. COO Peter Chernin, left in 2009. The perception among most television and advertising executives was that, as an unnamed member of the contingent told the trade journal Adweek, “the more Hulu succeeds, the more its partners fail.”

It’s unfortunate but understandable when mass media companies can’t find their way to the future. It is much worse when they are presented with it and reject it out of hand.

It wasn’t only that online advertising was generally selling for a fraction of the price of television—though that in itself seemed reason enough to resist. Hulu was also seen as making an end-run around cable and satellite providers (which were paying handsomely to carry the channels whose shows were now appearing online), as cannibalizing the by-now all-important home video market, and as hurting ratings (and therefore television ad rates) by cutting into broadcast viewing. Never mind that the DVD market was about to collapse anyway, or that, on a cost-per-thousand-viewer basis, Hulu commanded such a premium that it was actually selling its ad inventory at prices comparable to television’s. With Chase Carey, the former CEO of DirecTV, now in charge at News Corp., a different attitude prevailed.

Kilar made his case—or threw down the gauntlet, depending on your point of view—with a lengthy post on Hulu’s blog. “History has shown that incumbents tend to fight trends that challenge established ways,” he wrote, “and, in the process, lose focus on what matters most: customers. . . . Going forward, rapid innovation, low margins, and customer obsession will define the winners in pay TV distribution.”

You could almost hear the shouts of incredulity. Low margins—seriously? And who said anything about going forward? Within weeks, Fox moved to limit the availability of its shows on Hulu, denying subsequent reports of an immediate jump in online piracy. Then Hulu’s owners, which by this time included Disney in addition to NBC Universal and News Corp, put it up for sale.

They soon changed their minds and announced they were keeping it after all. At the beginning of this year, after months of speculation, Kilar resigned. Hulu’s owners put it up for sale again, then pulled it off again amid unconfirmed reports that the bidding had barely topped the $1 billion mark. Meanwhile, Netflix had gained a market cap of nearly $15 billion, not to mention 14 Emmy nominations.

It’s unfortunate but understandable when mass media companies can’t find their way to the future. It is much worse when they are presented with it and reject it out of hand. At this point, only one thing about Hulu is clear: Whoever disrupts television, it won’t be Fox and company.

September 1, 2013

September 1, 2013

Refusal to meet audience expectations is one symptom of the entertainment industry’s disconnect. Another, closely related, is the ongoing obsession with piracy. For years, the entertainment industry has been focused on stamping out illicit file-sharing through legal action—shutting down offending Web sites and randomly suing people who use them. Unfortunately, the Whac-A-Mole strategy has proven no more effective against piracy than it is against moles. But rather than lead the industry to re-evaluate its efforts, this has mainly acted as a spur to intensify them.

Refusal to meet audience expectations is one symptom of the entertainment industry’s disconnect. Another, closely related, is the ongoing obsession with piracy. For years, the entertainment industry has been focused on stamping out illicit file-sharing through legal action—shutting down offending Web sites and randomly suing people who use them. Unfortunately, the Whac-A-Mole strategy has proven no more effective against piracy than it is against moles. But rather than lead the industry to re-evaluate its efforts, this has mainly acted as a spur to intensify them.