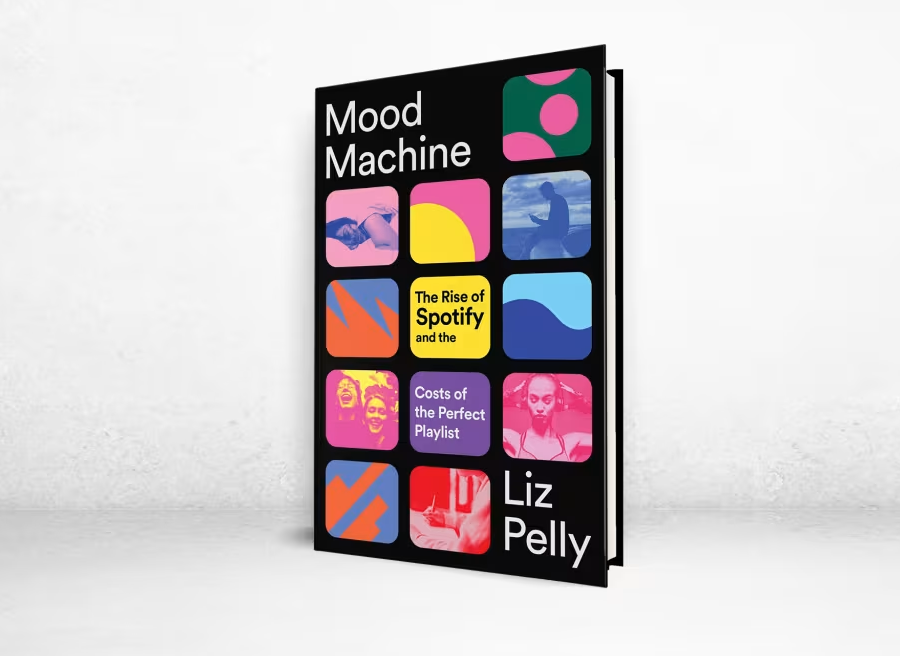

Martha Diamond: Deep Time will be on view November 17, 2024-May 18, 2025 at The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut, a 90-minute drive from Manhattan, following its initial appearance July 13-October 13, 2024 at the Colby College Museum of Art in Maine. This essay is an expanded version of the one that appears in the accompanying monograph, a 192-page hardcover with 65 color plates and essays and poems by Bill Berkson, John Godfrey, Vincent Katz, Eileen Myles and curators Levi Prombaum of Colby and Amy Smith-Stewart of The Aldrich. The book can be ordered from Amazon, Rizzoli or directly from the publisher.

IT’S BEEN MORE THAN FORTY-FIVE years since I first met Martha Diamond, and in that time my initial fascination with the person and her art has turned to something more like awe. Her early works were rooted in art history yet willfully strange: haystacks and other human constructions, not in their natural environment but floating, alone. All figure, no ground. A couple of years later, she homed in on what would become her signature style: highly abstracted cityscapes, executed with dizzying panache and a dazzling sense of color. With painting making a comeback after years of increasingly arid conceptualism—“I’m painting! I’m painting again,” squawked David Byrne, the former art student, on the Talking Heads track “Artists Only”—it was easy to see her as an artist in step with her time. Neo-Expressionism was on the rise, and Martha’s paintings bore many of its hallmarks: big brushstrokes, heroic scale, a return to figuration. Only gradually would it become apparent how unconcerned with fashion, how intensely personal, her work really was.

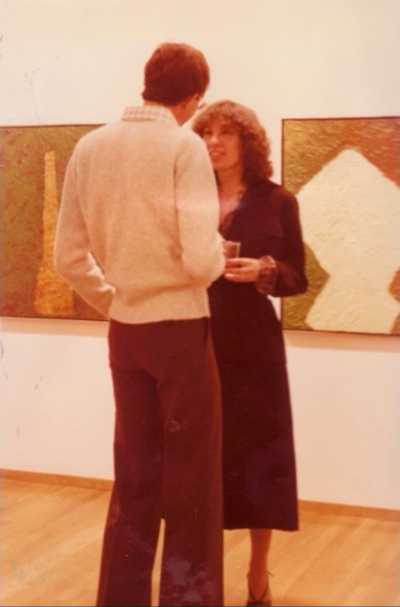

Frank Rose and Martha Diamond at the opening of “Martha Diamond: Paintings” at Brooke Alexander Gallery, New York, October 1978. Photo courtesy of the Martha Diamond Trust.

Both as an individual and as an artist, Martha was deeply orthogonal to the world. Behind the superficial resemblance to what was briefly in vogue were other qualities that marked her as her own woman: an unfailing sense of wonder, sometimes expressed in ways that led other people to think of her as naïve. (Could anyone else say “Golly!” with such conviction?) Grit and determination. (She liked men, but she was very clear that as an artist, she could never be anyone’s wife.) And unlike so many of her peers, a clear indifference to the market—not a bad attitude to have if you were a woman in the male-driven art world of the late twentieth century. She was an artist, not a careerist.

Which meant she was committed above all to her work. She didn’t talk about it all the time, but it certainly determined the way she saw the world. How she might use her hands as a framing device for anything in her field of vision. Her almost rapturous response to Russian Ark, the 2002 Alexander Sokurov film set entirely within the Winter Palace of imperial St. Petersburg. In one continuous, eighty-seven-minute take, Sokurov’s camera glides through three centuries of Russian history as it played out in the palace, culminating in a sumptuous re-creation of the grand ball that took place there in 1913, on the eve of the war that would end with the destruction of everything the palace represented (though not the palace itself, which survives as the greater part of the Hermitage). The film treats time as a mirage; space, seen through the camera’s roving, peephole-like view, exists only within the blinkered confines of its lens. Martha remembered a minute or two into the film that she’d already seen it, but no matter—she was there for the spectacle, the mirage, the frame and the ecstasy within it. So we stayed.

It took me awhile to realize this, but eventually I saw something akin to Sokurov’s carefully plotted, endlessly rehearsed, single-take movie in the way Martha worked—for though her paintings often look deliriously spontaneous, her process was exactly the opposite. Her large canvases—seven or eight feet high by five, six, even ten feet wide—generally began as oil studies on small Masonite boards. Then she would use charcoal to plot out the design on a canvas, blowing it up to much larger proportions. Only then would she start the painting itself. She would go wet-on-wet, a tricky thing to manage, made even trickier by the fact that though she was right-handed, she painted with her left. (“The paintings are blunt,” Alex Katz once said. This explains why.) And once she started painting, she would keep going for hours nonstop, through the night if necessary, barely even pausing until the work was done. Single take. Action painting. New York School.

Because New York School is the font from which Martha’s work springs. When she returned to the city in 1965 after getting her B.A. in Minnesota and then spending a year in Paris and traveling through Europe, she fell in with New York School poets and took inspiration from New York School painters. She grew fascinated with Jackson Pollock. She felt a kinship with Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Franz Kline. Under their influence she became a latter-day action painter, not simply making art objects but performing in the process for an audience of none. This explains a lot, starting with the brush strokes.

In 1989, answering some questions from the poet Bill Berkson as he was preparing an article for Artforum, Martha admitted to some expressionist tendencies—distorted imagery, monumental scale, extravagant colors. But then she wrote, “I’m more concerned with a vision than expressionism and I try to paint that vision realistically—I try to paint my perceptions rather than paint through emotion.” This may come as news to realist painters, or to anyone fighting off spatial confusion: She painted what she actually saw? “I know the city has straight lines or edges,” she continued, “but as I walk around, the ending or beginning of substance becomes less absolute. At night, where buildings are higher than streetlights, often you can’t see the tops or edges above. Dark areas around lights appear blurred. . . Light and rhythm . . . That’s where my spirituality lies.”

“Carriage,” 1990. Oil on canvas, 72 x 60 inches. Collection High Museum of Art, Atlanta; gift of the Alex Katz Foundation. Copyright © the Martha Diamond Trust.

August 13, 2024

August 13, 2024