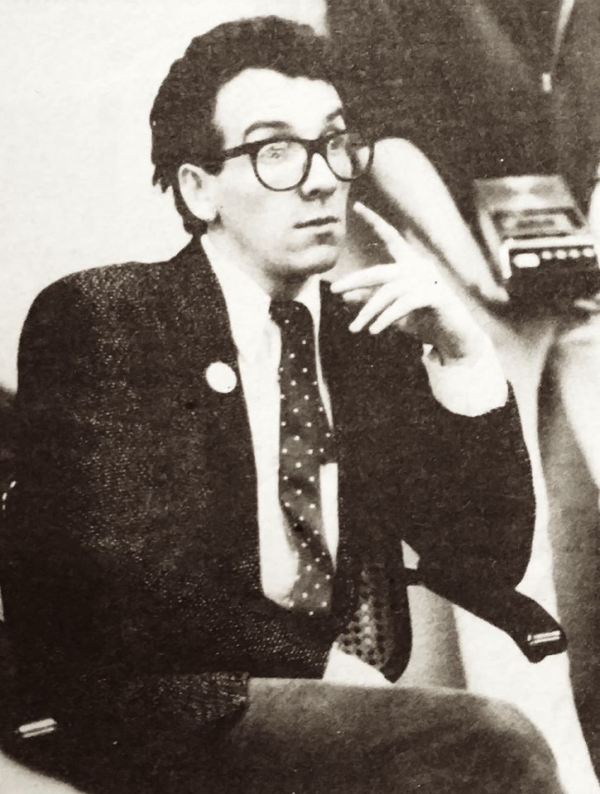

Photo: Chuck Pulin

UNLIKE THE FIRST ELVIS, this one swivels from the knees. Clever, this move: with the moniker and the spiteful little persona, it seems intended to give a rough approximation of the distance we’ve traveled (some of us, anyway) since Presley pushed the pelvis button back in 1956. From desire to frustration, Costello is saying, from lust unbounded to tearful rage; from sexual revolution to civil war. This is the man who said in one of his rare interviews that the only two things that matter to him are “revenge and guilt.” (“Love? I don’t know what it means, really, and it doesn’t exist in my songs.”) According to reports, he even keeps a little black book for all his enemies in the music business – right down to the poor schmucks who’ve gotten free tickets to his concerts and then failed to show. Weird stuff — although none of it would matter if he weren’t so inspired.

It’s interesting that one of the most exciting rock heroes to emerge in years is also the most unlikely looking. Physical resemblances to Woody Allen and Buddy Holly have already been noted: he reminds me more of a new wave Mehachem Begin, especially as regards the embattled set of the jaw. Yet he makes music that’s clever, concise, bouncy, explosive, dangerous, unforgettable, and so precisely structured as to have an almost architectural presence. At his best, Costello gives the impression of advancing knock-kneed on the world at the head of a pulsing phalanx of sound. I think he has a vision of himself as the Avenging Dork.

Last Friday afternoon, however, the avenger had some explaining to do. It was the beginning of Elvis Costello Weekend, a three-day sequence of concerts and club dates in New York and New Jersey, and Costello felt compelled to explain the bizarrely racist and xenophobic outburst reported in that week’s Voice. According to Bonnie Bramlett, one of three sources for the story, Costello had started a barroom brawl by lashing out in shocking and ugly terms at black people in general and James Brown and Ray Charles in particular. So he took the hot seat in a small conference room crowded with newspaper, radio, and magazine reporters whose attitudes ranged from frivolously amused to quietly outraged. “How do you spell ‘petard’?” someone asked, just before Elvis stepped into the room.

Before and After Punk |

A mild-mannered music writer goes to this dive bar on the Bowery. . . |

Why Elvis?The King was just a sweet mama’s boy whose vague dreams of stardom took him places he’d never dreamed of.

|

Minimal and MysticalWhat does “Einstein on the Beach” have to say to us in this post-Minimal era?

|

Laurie Anderson, Multimedia Techno-WaifA spiky-haired extra-terrestrial stumbles forward into the future.

|

A Rotten Success StoryPublic Image Ltd.: Are they committing rock’n’roll suicide, or are they simply boring?

|

Dee Dee Ramone Didn’t Wanna Be a Pinhead No MoreSo the New York rocker who practically invented punk kicked heroin, bought a dinette set, and married Vera, who was, you know . . . normal.

|

Discophobia!Rock & roll fights back.

|

Peter Townshend Gets Old Before He DiesThe leader of the Who has been questioning his role in the youth cult for most of this decade.

|

Elvis Costello Wins Friends and Influences PeopleLast Friday afternoon, the avenger had some explaining to do.

|

Danny Fields Is a Number-One Fan“When I first saw the Ramones I went up to them after the set and—‘You guys are great! You guys are great!’ That’s all I could say.”

|

Four Conversations with Brian EnoHe can look into an interviewer’s face and measure the determination to report something weird.

|

The Butch Fantasy: America Goes PunkCBGB or the Eagle? Both bars traffic in mythic projections of masculinity. But as someone who’s hung out in each, I’ve been known to get confused. And why not? It’s a natural response to being dropped into mirror worlds.

|

April 9, 1979

April 9, 1979