The Art of Immersion

How the Digital Generation Is Changing Hollywood, Madison Avenue, and the Way We Tell Stories

"In his fascinating new book, [Frank Rose] talks about how the Internet is changing the way we create and consume narrative. . . . 'We are ceasing to be consumers of mass media,' says Rose, 'we are becoming participants in social media—a far more fluid environment in which we simultaneously act as producers, consumers, curators, and commentators.'"

— Ariana Huffington, The Huffington Post"We’re in the midst of a fascinating — and delirious, often overwhelming — cultural moment, one that Rose, with his important new book, astutely helps us to understand."

— Holly Willis, KCET-TV Los Angeles"Compelling . . . From 'Star Wars' to 'Lost' ('television for the hive mind'), it is the immersive, 'fractal-like complexity' of storytelling that turns on digital audiences and sends them online to extend the fantasy via wikis, Twitter and blogs."

— P.D. James, The Guardian (London)"Like Marshall McLuhan’s groundbreaking 1964 book, 'Understanding Media,' this engrossing study of how new media is reshaping the entertainment, advertising, and communication industries is an essential read."

— Library Journal"A highly readable, deeply engaging account of shifts in the entertainment industry which have paved the way for more expansive, immersive, interactive forms of fun . . . accessible and urgent."

— Henry Jenkins, author of "Convergence Culture""We can spy the future in Frank Rose’s brilliant tour of the pyrotechnic collision between movies and games. This insightful book convinced me that immersive experiences are rapidly becoming the main event in media. . . . Future-spotting doesn't get much better than this."

— Kevin Kelly, author of "What Technology Wants""Himself a master of good old-fashioned narrative, Frank Rose has given us the definitive guide to the complex, exciting, and sometimes scary future of storytelling."

— Steven Levy, author of "Hackers" and "In the Plex""Frank Rose has written an important, engaging, and provocative book, asking us to consider the changes the Internet has wrought with regard to narrative as we have known it, and making it impossible to ever watch a movie or a TV show in quite the same way."

— Peter Biskind, author of "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls" and "Down and Dirty Pictures""The Web lets us dive deeper than ever before, though into what is up to us. . . . For those of us lagging behind, wading rather than diving into art's new cyber-sphere, Frank Rose makes an excellent guide."

— The Atlantic"An essential overview. . . . Applications in the academic world are clear (it is already on the syllabi for classes at USC and Columbia), but it also constitutes a prerequisite for those wishing to enter Hollywood, and marketers or PR professionals wishing to engage an increasingly fragmented audience."

— International Journal of Advertising"It's a grand trip, taking in everything from Charles Dickens to Super Mario and 'Avatar.' The book is meticulously researched, persuasively constructed and benefits from an impressive level of access."

— New Scientist"For anyone even remotely interested in a how-we-got-here-and-where-we’re-going guide to interactive, socially networked entertainment, it’s an essential read."

— Empire (UK)"The Internet, as Frank Rose writes in 'The Art of Immersion,' 'is the first medium that can act like all media. It can be text, or audio, or video, or all of the above. . . .' According to Rose, 'a new type of narrative is emerging – one that’s told through many media at once in a way that's nonlinear, that’s participatory and often game-like, and that’s designed above all to be immersive. This is deep media.'"

— Robert McCrum, The Observer (London)"The Internet has altered many habits of life, but is it powerful enough to change the way we tell stories? Frank Rose, longtime writer for Wired and author of the book 'The Art of Immersion,' thinks so. . . . The author explains that every new medium has disrupted the grammar of narrative, but all had a common goal: to allow the audience to immerse themselves in the stories that were being told."

— La Stampa (Turin)"For an authoritative tour of the frontiers of amusement, read the just-published 'The Art of Immersion.' Perhaps the 3-D game version is forthcoming?"

— The MarginalianWe are witnessing the emergence of a new form of narrative that is native to the Internet.

IN THE 20TH CENTURY WE WERE SPECTATORS, passive consumers of mass media. Now, on YouTube and Facebook and TikTok, we are media. And we view television shows, movies, even advertising as invitations to participate — as experiences to immerse ourselves in at will.

The result is an approach to narrative that never existed before. Just as the printing press gave rise to the novel and the motion picture camera led to the invention of cinema, today’s digital tools are encouraging us to develop new kinds of stories. Told through many media at once in a nonlinear fashion, these new narratives encourage us not merely to watch but to participate, often engaging us in the same way that games do. This is “deep media”: stories that are not just entertaining but immersive, that take you deeper than a 30-second spot or an hour-long television drama or a two-hour movie will permit.

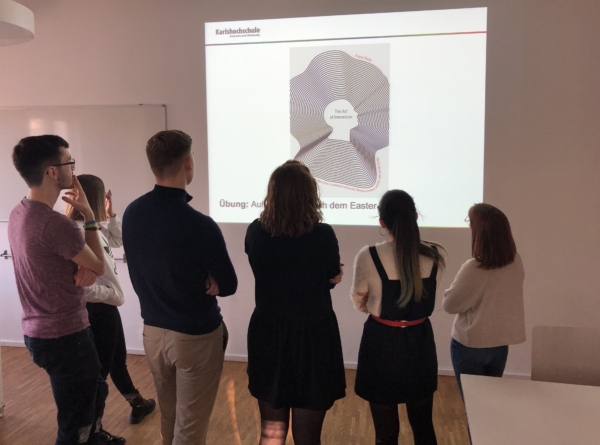

Management students in Karlsruhe, Germany ponder the meaning of the red dots on the cover. Photo: Thomas Zorbach

Writing in the Italian daily La Repubblica, the novelist Giorgio Vasta put it this way: “In ‘Continuity of the Parks,’ Julio Cortázar imagines a man at the end of the day as he sits in his favorite armchair and goes back to reading a novel. The scene that passes before him portrays the furtive movements of someone about to commit a crime. Through a rotation of 360 degrees, the reader of Cortázar’s story follows the reader of the novel, who in turn is following the final steps of a criminal wielding a knife as he passes through the rooms of a house and comes up behind a man sitting in a chair. . . . Frank Rose’s account of storytelling in the Internet age reflects on this paradox: How is it that stories — the ones we read, watch at the movies or on TV, or follow (and help construct) on the Internet — are able to walk up to our chair and be not only behind us but all around us? Because stories no longer stay in their place. We don’t find them only in books, onscreen, on a DVD or in a theater. . . . They are behind us, beside us, above us, embedded in our bodies.”

This is why the AIGA Design Educators Community put The Art of Immersion on its “required reading” list, calling it “a primer for experience design.” And why the International Journal of Advertising called it “an essential overview . . . a prerequisite for those wishing to enter Hollywood, and marketers or PR professionals wishing to engage an increasingly fragmented audience.”

But what does it mean that stories no longer stay in their place? That they are everywhere, of course, but more than that. It means that storytellers of every sort — authors, filmmakers, show runners, game designers, advertisers, marketers — need to function in a world in which distinctions that were clear in the industrial age are becoming increasingly blurred:

The blurring of author and audience: Whose story is it?

The blurring of story and game: How do you engage with it?

The blurring of entertainment and marketing: What function does it serve?

The blurring of fiction and reality: Where does one end and the other begin?

In THE ART OF IMMERSION, Frank Rose explains why this is happening, and what it means for us all.

Published by W.W. Norton in the US and the UK ● Available in hardcover, paperback and as an ebook ● Also published in France, Italy, Japan, Korea and Taiwan ● Excerpted in Wired, Wired UK and Contagious

Henry Jenkins interviews Frank Rose:

. . . Throughout the book, it seems you see these creative changes towards a more immersive and expansive entertainment form being fueled by the emergence of games. Why do you think computer and video games have been such a “disruptive” influence on traditional practice in other entertainment sectors?

Rose: Because they engage the audience so directly, and because they’ve been around long enough to have a big influence on other art forms. Movies like Inception, as you’ve observed, are constructed very much like a game, with level upon level upon level and a demanding, puzzle-box approach to narrative. If you’re a gamer, you know intuitively how to approach this. If you’re not, well, good luck.

One of the reasons I started this book was that I’d begun to meet screenwriters who’d gone from TV to games and back again, and when they came back it was with a different approach to narrative—moving across multiple levels, thrusting you directly into the story and letting you figure it out for yourself, that kind of thing. But at first I just had this vague sense that games and stories were blurring into each other—that in some way that I didn’t fully understand, games were becoming stories and stories were becoming games. I got obsessed with trying to understand the relationship between the two. I spoke with a lot of game designers, but it wasn’t until I got to Will Wright that I found someone who could . . .

Read the full interview

Read the three-part excerpt in Wired:

1: Why Do We Tell Stories?

What is it about stories, anyway?

Anthropologists tell us that storytelling is central to human existence. That it’s common to every known culture. That it involves a symbiotic exchange between teller and listener — an exchange we learn to negotiate in infancy.

Just as the brain detects patterns in the visual forms of nature — a face, a figure, a flower — and in sound, so too it detects patterns in information. . . .

Jimmy Fallon (right) with “Lost” showrunners Carlton Cuse and Damon Lindelof at Comic-Con

2: The Star Wars Generation

Adam Horowitz blames the whole thing on Star Wars.

Horowitz — who with his writing partner, Eddy Kitsis, was an executive producer on Lost and a screenwriter for Tron: Legacy — remembers seeing Star Wars in Times Square with his mom when he was five. As soon as it was over, he wanted to go right back in. “But there’s no bigger Star Wars geek than Damon Lindelof,” he admits. . . .

3: Fear of Fiction

Two years ago this month, as editors worldwide were beginning to debate whether anyone would actually go see Avatar, the $200 million-plus, 3-D movie extravaganza that James Cameron was making, Josh Quittner wrote in Time about getting an advance look. “I couldn’t tell what was real and what was animated,” he gushed. “The following morning, I had the peculiar sensation of wanting to return there, as if Pandora were real.”

It was not the first time someone found an entertainment experience to be weirdly immersive. . . .

Frank names the five best books on pattern recognition

When asked to recommend his favorite books on any subject, Frank chose pattern recognition. It’s a thread that runs through nearly all his work over the past 15 years, starting with The Art of Immersion and continuing with The Sea We Swim In and his executive education program in Strategic Storytelling at Columbia University. The ostensible subject throughout is storytelling—but pattern recognition is what storytelling is all about. Here are five books that in different ways deal with humans’ capacity for pattern recognition and what drives it—our need for some semblance of structure in a seemingly random world.

How Stories Work in a Data-Driven World

"If you want to connect with customers — that is, with the audience for the experience you’ve created — Frank Rose shows not only that you have to think narratively but how to go about it, element by element. And he wonderfully exemplifies his ideas, for his stories about storytelling are superbly written and expertly woven together. Read this book to be immersed in the sea of storytelling that's so crucial to business success today."

— B. Joseph Pine II, coauthor of "The Experience Economy" and "Authenticity"WE SWIM IN A SEA OF STORIES — stories that determine how we comprehend the world, that define our personal lives, our professional lives, our goals and ambitions and ideals. They can control us, or we can control them — if we know how they work. More about this book...

The End of Innocence at Apple Computer

"The saga of Apple in its early years is a case study of the California style of creativity smashing headlong into the realities of Wall Street. Once again, Californians came up with a revolutionary idea which the Northeast seized control of and institutionalized. . . . Frank Rose has written the book on Apple and the entire Silicon Valley phenomenon."

— Kevin Starr, author of the eight-volume "Americans and the California Dream" seriesIT SEEMS UNTHINKABLE TODAY—but forty years ago, when personal computers were still new and the World Wide Web had yet to be invented, Steve Jobs was cast out of Apple. And it wasn't just Wall Street that applauded—it was most of Silicon Valley. More about this book...