February 3, 2009

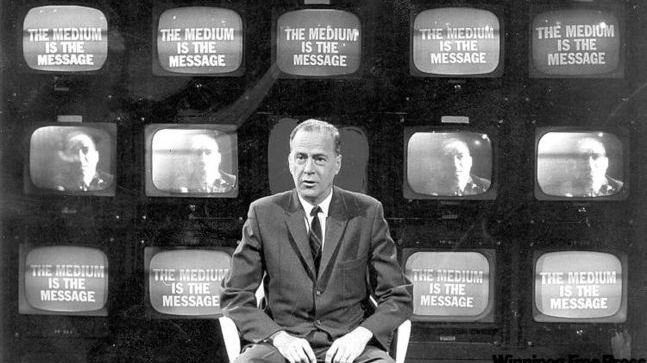

In thinking about deep media, I’ve been rereading McLuhan. And one thing that’s struck me is how much the idea of media that’s participatory—that you don’t just consume but in some way help complete—is central to his thinking. What determines whether a given medium is “hot” or “cool”? Basically, it’s whether that medium requires participation. Or as McLuhan put it in Understanding Media,

A hot medium is one that extends one single sense in “high definition.” High definition is the state of being well filled with data. A photograph is, visually, “high definition.” A cartoon is “low definition,” simply because very little visual information is provided. Telephone is a cool medium, or one of low definition, because the ear is given a meager amount of information. And speech is a cool medium of low definition, because so little is given and so much has to be filled in by the listener.

Type is “hot” because because it’s linear and rational—because it quite literally spells everything out. Television is “cool” by virtue of its being fuzzy. With television—especially with the interlace systems of the 1960s, which split the image into horizontal lines and refreshed first the odd-numbered lines and then the even-numbered ones—you have to work to fill in the blanks. Paradoxically, all this mental activity results in the somnambulistic state we call vegging out.

Nobody thinks of television as participatory these days, but it took a lot of brain cells to sit in front of a cathode-ray tube and soak up all those electron-gun emissions. The invention of the remote and the advent of channel-surfing invited participation in a more conventional sense. For McLuhan, “hot” and “cool” weren’t binary states; they existed on a continuum. And now that TV is going high-definition—that is, now that it’s being filled out with data—it’s also becoming less “cool.” Television is moving toward the hot pole just as it’s starting to be superseded by the incredible proliferation of low-res video on the Internet. Low-res but high-participation, in every sense of the word.

I don’t know that McLuhan anticipated the depth of participation the Internet invites today. But he certainly sensed where we were headed. For him, the turning point wasn’t digital; most media in the 1960s were still analog. The turning point came much earlier, when the world went electric—because with electricity comes speed, and with speed comes simultaneity. Everything happening at once. More than you can keep up with. Going digital just sped things up even more. Good-bye couch potato, hello ADD.

Comments

Tim McCormick

- April 17, 2009

Thank you Frank for retro+ing McLuhan. I wish that his name could become more than a Woody Allen movie trivia reference.

I have believed that McLuhan was able to provide an actual tenor to the voice of reason aptly measuring the effects of increasingly sophisticated communication efforts towards increasingly vulnerable minds.

Maybe one of your upcoming tomes will address the words and impact of Mcluhan's all too brief orbit.

Please and good luck.

Fritz Clapp

- May 15, 2009

Similarly motivated earlier this year to revisit McLuhan, I was delighted to find Laws of Media: The New Science published with his son Eric in 1988, highly recommended for those of us trying to adjust (again) to the paradigm shifts.