May 3, 2012

Last June, when I gave the opening keynote at the Crossover Summit at Sheffield Doc/Fest, I was asked to talk about the relationship between games and stories. It’s a meaty topic: If stories in the digital age are becoming participatory (alternate reality games like 42 Entertainment’s Year Zero with Trent Reznor, or the “response” videos from Wieden+Kennedy’s “The Man Your Man Could Smell Like” campaign for Old Spice), then almost by definition they would be turning gamelike as well.

As one of the leading events on the international documentary circuit, Sheffield was a good venue for this discussion. The summit, produced by London’s Crossover Labs, attracts filmmakers and television executives from across Europe and beyond, so I thought I’d give a little background.

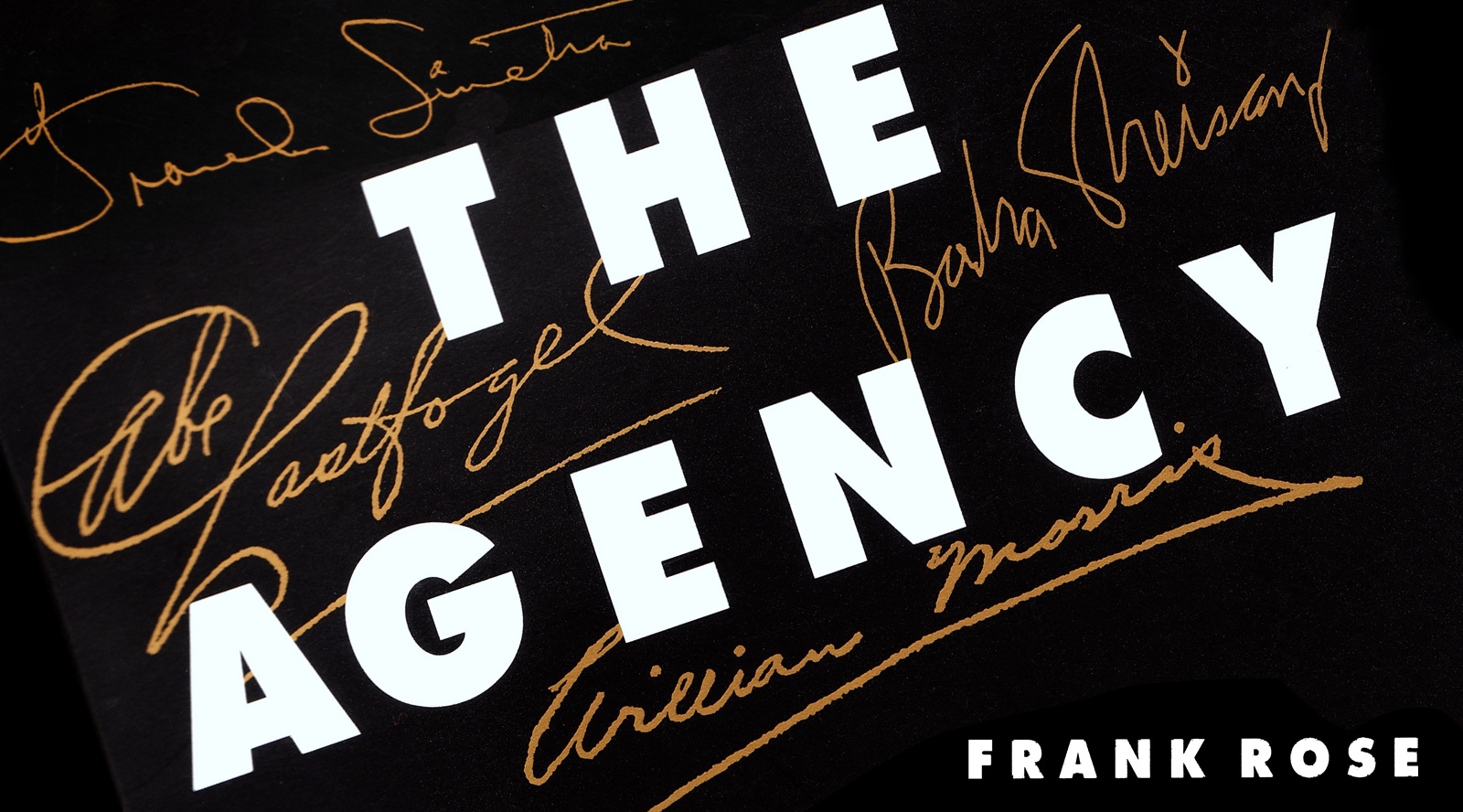

The blurring of the lines between games and stories was one of the key questions I had when I started working on The Art of Immersion in 2008. It was already obvious that, even as stories were growing gamelike, video games (Heavy Rain, for example) were becoming more and more narrative-driven.

“We have the opportunity to make the player the hero,” Phil Spencer, head of Microsoft Game Studios, told me early on. “That’s something movies and television can’t do. But it begs the question, What is the player doing to attain that status? The way to do that is through story. You build a narrative arc and let the player play through it.”

So stories were becoming games and games were becoming stories. But what did that mean, exactly? And what were the implications for filmmakers and game developers? That’s what I was trying to get at in the book, and in my talk as well.

It’s no secret that a many top game designers—Cliff Bleszinski, Hideo Kojima—are seriously in thrall to the movies. But for all their movie envy, game developers have not been able to match cinema’s narrative and emotional force.

In part that’s because they keep running up against the still-considerable limitations of gaming hardware. In Fable II, set in the mythical land of Albion, Peter Molyneux gives you quests to fulfill whilst you roam the countryside, have sex, get diseases, get rich, kill people, save people, etc. In most games the opportunities for personal interaction are limited to talking and shooting, but Molyneux wanted his players to be able to express emotion.

To do that, he devised an “expression wheel” that let you smile, laugh, flirt, even fart. Simply by pressing some buttons on the controller, you could dial up the appropriate response. But what was intended as a way of extending the game’s emotional range succeeded mainly in highlighting how pathetically clunky emotional expression in video games remained. “You pressed a button—it all seemed so trivial,” Molyneux lamented. “That’s not how it’s done in real life!”

Bleszinski took a less ambitious approach with Gears of War. In Gears you play Marcus Fenix, a major-league tough guy, and you earn your hero status by defeating the Locust Horde, a nasty assemblage of beasts and humanoids that has all but annihilated the human population.

Gears is not a mindless shooter. It’s designed to reward stealth, cunning, and tactical thinking; the look is vivid with detail, in the way a fictional world has to be to feel convincing. And the story, while thin, is nonetheless capable of conveying drama and emotion—as in the excruciating scene in Gears 2 when Marcus’s sidekick Dom finally finds his long-lost wife, Maria, only to realize she’s been terminally damaged by torture.

“Gears of War will never be remembered as a great work of fiction,” Bleszinski admitted cheerily, “and we’re okay with that. I find that a lot of the narrative in video games exists just as a cool excuse for fun things to happen to the player. But it’s not just story. Often it’s the premise—the setup, the context of your actions, the way it makes you feel you’re in the world.”

A New Grammar of Fun

In a New Yorker profile that was later incorporated into his book Extra Lives, Tom Bissell described Bleszinski and his peers as having “established the principles of a grammar of fun.” That’s certainly the idea, but Bleszinski’s own assessment was more modest, and probably more accurate. “My two loves have been video games and films,” he told me. “But movies have had 75 years to teach audiences what to feel. We’re still continuing to master our craft.”

Movie-makers certainly took long enough to hit their stride: It was 1910, roughly 20 years after the invention of the motion-picture camera, before they even caught onto the idea of stars. Until then, film actors were kept anonymous in a misguided attempt to hold down their salaries. But games are participatory by definition, and that introduces an issue even knottier than actors’ salary demands: control. The designer creates the game, but the player decides what to do next—so who’s controlling the story?

One way of settling the matter is to neutralize the player by deactivating the game controller. That’s the Kojima approach. Kojima is the master of the cut scene, those little video interludes that come between bouts of gameplay, advancing the plot while the player watches patiently (or not). In Metal Gear Solid 4, the most recent full-bore installment in his ongoing saga, Kojima idles the controller for nearly a half hour at a time—more than eight hours in total.

In cinematic terms, cut scenes are more or less on a par with the proscenium arch shot, which is done with a single, stationary camera planted front-row center, as if to record a stage play. That’s what early movie directors used before they invented cuts, fades, pans, and close-ups—techniques that allowed them to take advantage of their new medium’s possibilities. Cinema didn’t make any real headway as an art form until it ceased to mimic stage-acting and developed its own grammar of fun.

Rockstar Games took a big step forward last year with L.A. Noire, a scripted detective story set in 1947 Los Angeles. Detective stories are implicitly participatory anyway, as generations of Sherlock Holmes fans can attest. But in this one you don’t have to content yourself with second-guessing the endlessly clever protagonist; you get to examine the evidence and question witnesses and suspects yourself. Since a great deal depends on your ability to read faces and body language, It doesn’t hurt that the characters are portrayed by professional actors, or that their performances were recorded using a motion-capture technology that rivals James Cameron’s for sophistication.

Still, it wasn’t until I spoke to Will Wright, creator of SimCity and The Sims, that I really began to understand the relationship between games and stories. In open world games like The Sims, there’s no scripting at all. Instead, the story emerges from the complex and often unpredictable interaction of characters created by the player and rules laid down by Wright.

“I love movies,” Wright told me when I interviewed him for the book. “But I’ve never wanted to tell a story in a game.” He’d rather let the player tell the story. Which is how you get Alice and Kev, a blog about two Sims characters created by Robin Burkinshaw, a game design student in England.

Burkinshaw made Kev mean-spirited and insane and his daughter Alice sweet but unlucky and suffering from low self-esteem. Then he took away their money and left them living in a park. What happened after that was determined largely by the game itself. When Burkinshaw sent Kev to look for romance in the park, he turned up without any clothes. Alice grew increasingly depressed and angry until finally she told her father off—much to his surprise, and Burkinshaw’s.

“Think of Star Wars,” Wright said. “You’ve got lightsabers and the Death Star and the Force and all this stuff that leads to a wide variety of play experiences. I can go have lightsaber battles with my friend. I can play a game about blowing up the Death Star. I can have a unique experience and come back and tell you a story about what happened. The best stories lead to the widest variety of play, and the best play leads to the most story. I think they’re two sides of the same coin.”

This doesn’t solve the control question, of course. But it does put the issue in perspective. If stories (documentaries, for example) are going to be gamelike, the storyteller has to make room for users. That doesn’t necessarily mean giving them control of the story, as Wright does, but it does mean not hogging the game controller. How this compromise should work is something people are still sorting out—but at the stage where we are now, that’s to be expected. What’s great about being a storyteller today is that you get to help figure out the answer.

Comments

Comments are closed here.