November 27, 2013

For a couple of years now, “transmedia” has been the buzzword most people use to define storytelling in the digital age. But while telling a story across different media formats (video, text, game, what have you) can be an effective way to engage people in a narrative, it’s not the only way—nor is it necessarily the best. One of the most effective means of creating an immersive narrative is in fact one of the oldest: by serializing it.

I was reminded of this recently when I went to Turin to speak at Scuola Holden, a “school of storytelling and the performing arts” founded 20 years ago by the novelist Alessandro Baricco. Named after that world-class narrator Holden Caulfield, this unconventional institution (no teachers, for a long time no tests, and certainly no phonies) was intended to be a place where young Caulfield might feel at ease. Instead of hiring professors, the school brings in professional storytellers; and instead of focusing on technical skills like journalism or filmmaking, it tries to foster an aptitude for telling stories in any medium.

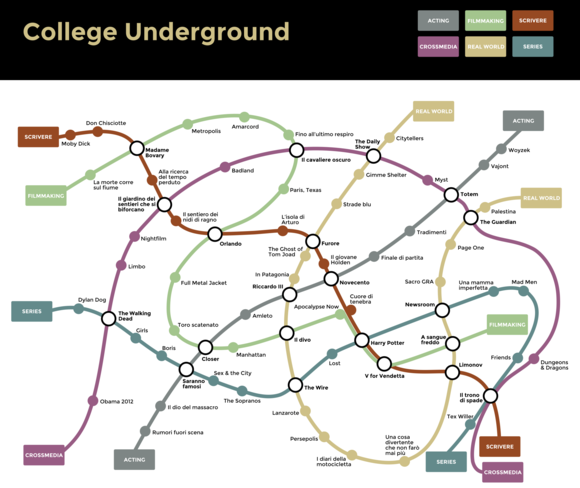

Nonetheless, students are expected to spend about half their time during the two-year program in one of six “colleges”: Scrivere (writing), Filmmaking, Series, Crossmedia, Acting, and “Real World”—that is, stories inspired by actual events. In the first month of the school year, people like me were brought in to describe what these different disciplines were all about. I was asked to talk about Series. Then I was handed the map above, which I decided to redraw a bit. The point was to show how serialization can create a sense of immersion.

First stop: The Walking Dead, where Series does indeed intersect with Crossmedia. Currently one of the most-watched television shows in America, The Walking Dead is a marvel of participatory entertainment. It offers not only online spinoffs—Webisodes and games—but others that take place offline, such as the zombie school the AMC Network runs for people who are hoping to be cast as extras. And then there’s The Talking Dead, Chris Hardwick’s talk show about the show, which has proven so popular it’s now been expanded to an hour. Webisodes are hardly groundbreaking at this point, though they can be effective when done well. But a school for extras—much less a meta-show? Gale Anne Hurd, producer of The Walking Dead (and Aliens and The Terminator well before that), is showing the industry how fans should be engaged.

From there we followed the Series and Crossmedia lines back in time to Star Wars for a three-way rendezvous with Filmmaking. As Howard Roffman, the Lucasfilm executive who created what’s come to be known as the Star Wars Expanded Universe, explained in The Art of Immersion, the key to creating an all-but-limitless series of stories out of Star Wars was the incredible amount of detail George Lucas packed into his original picture. The term Lucas used was “immaculate reality,” Roffman told me. “You could zoom in on any section of any frame and have a hundred stories to tell. But it wasn’t because he ever imagined anybody would zoom in like that—he just wanted to make it feel real.”

Third stop: Lost, which used an overabundance of detail not to generate new stories but to encourage participation. (The producers of Lost experimented with transmedia as well, but not as successfully as they’d hoped.) “Lost creates the illusion of interactivity,” said Damon Lindelof, who created the show with J.J. Abrams. “This show is ambiguous. We don’t say what it means.” Long before The Walking Dead, Lost became an Internet phenomenon, because fans needed some way to figure out what was going on—which is what prompted a young computer consultant named Kevin Croy to start Lostpedia, one of the first TV fan wikis, in September 2005. Abrams and Lindelof didn’t plan it this way, any more than George Lucas planned to use “immaculate reality” to launch an entire story world. But by telling their story in nonlinear fragments and leaving it to the audience to piece them together, they invented a new form of interactive fiction.

After Lost it seemed only natural to make a connection with Scrivere at Charles Dickens—and in particular, Oliver Twist. Obviously I could have followed the prescribed route and talked about Harry Potter, but Dickens strikes me as a much more interesting case. Instead of writing a series of novels, he wrote novels in serial form, publishing them in multiple installments over a period of many months. He had good reasons for doing so, starting with the fact that many of his readers were too poor to buy an entire book. But as with Star Wars and Lost, his decision had unintended consequences. Oliver Twist—the first installment of which appeared in February 1837, the month Dickens turned 25—and the novels that followed were all written on deadline. This meant that his readers had an opportunity to weigh in with their own thoughts while the book was still being written. As John Butt and Kathleen Tillotson observed in their landmark 1957 study Dickens at Work, “Through serial publication an author could recover something of the intimate relationship between story-teller and audience which existed in the ages of the sagas and of Chaucer.”

Next stop on the Series and Scrivere lines: J.R.R. Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien didn’t publish his Hobbit books in serial form, but he was among the first to articulate the idea of the story world—the kind of elaborately conceived fictional universe that Lucas realized decades later in Star Wars. As Tolkien explained in his essay “On Fairy Stories” (first presented as a lecture at the University of St. Andrews in 1939, shortly after he’d begun the Lord of the Rings trilogy), the world-builder “makes a Secondary World which your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is ‘true’: it accords with the laws of that world. You therefore believe it, while you are . . . inside. The moment disbelief arises, the spell is broken; the magic, or rather art, has failed.”

Final stop: Game of Thrones (Il trono di spade on the map), where Series and Scrivere make a connection with Crossmedia. In an earlier post I wrote about the work Campfire did to introduce the show to HBO viewers and George R.R. Martin fans. It consisted of a series of physical objects—bottles of scent, a map, some scrolls—to evoke the story world Martin had created. On the back of a map that had been sent to the fan blog Winter Is Coming, someone found some all-but-illegible lettering that was eventually discovered to read, “Always Support the Bottom.“ But what did that mean? Fans went nuts trying to figure it out. Finally Campfire creative director Steve Coulson tweeted that it was an error, not a clue. But by this point the fans had gone too far to accept that it was just an accident. “Always Support the Bottom“ became a sort of shorthand for fan fanaticism. To Campfire it became something else as well: a reminder that, as Coulson put it, “No community is too small to take note of. You want to make sure they know you’re listening.”

Series like The Walking Dead and Game of Thrones are not only changing what we expect from TV; they’re changing the definition of entertainment. But we need to remember that they spring from a much older tradition. From Dickens to Lost to these most recent iterations, they serve to remind us that it’s all about creating a community—or to put it more accurately, creating the conditions in which a community can flourish, and then listening to what that community has to say. You need to build a story world. Embrace serendipity. And always support the bottom.

Comments

Comments are closed here.