November 30, 2011

Late last month I got an advance look at the new IPG Media Lab, recently relocated from LA to New York and sporting all manner of flashy tech displays. Where the LA lab was essentially a connected-home display designed to show marketers how people are actually consuming media today, as opposed to five or ten years ago, the New York lab is all about future possibilities and the technologies that enable them. There’s GazeHawk, which uses Webcams to do eye-tracking studies. There’s TruMedia’s iCapture, an “audience measurement solution” that computes the age, sex, and interest level of people looking at in-store displays. Affectiva, whose “Affdex expression tracker” watches shoppers through a tiny camera tucked under the shelf and measures their emotional response to the products thereon. And then there’s Trendrr—”a company we love,” says Chad Stoller, the lab’s managing partner.

Trendrr sifts through social media commentary to gauge the engagement level of people watching TV. This is a potentially revolutionary development—for advertisers, for viewers, for television itself.

For all the attention paid to the attention economy—the idea that in a world with a super-abundance of information, attention is what’s scarce and therefore valuable—it has had remarkably little impact on the television business. For decades, network programmers have sacrificed shows with a passionate following because their numbers didn’t cut it. The most notorious example is the original Star Trek, which ran for three seasons between 1966 and 1969: After ending its first season as the #52 show on prime time, it was shunted off to a dismal time slot and eventually killed, despite an unparalleled fan campaign to keep it on the air.

Forty years later, not much had changed. As Time magazine’s James Poniewozik patiently explained in a 2009 blog post about fans’ efforts to persuade NBC to renew Chuck despite its Nielsen deficit, “Four million people who watch a show really hard are still just four million people to an ad buyer.”

Except, of course, that in the case of Chuck, they actually added up to more. Faced with a media-savvy fan campaign that leveraged a major sponsor (Subway) and attracted more than 20,000 members on Facebook, the network relented. The question now is whether, with the rise of social TV and the ability of companies like Trendrr to measure online commentary, network executives will consider viewer engagement a barometer of success as a matter of course—without the viewers having to campaign on Facebook to make themselves heard.

Mark Ghuneim, the CEO of Wiredset, the New York company behind Trendrr, sees that day coming. Trendrr is one of several outfits—including Nielsen’s Buzzmetrics unit, which focuses on social-media conversations about brands—that uses data-mining techniques to parse what people are saying on Twitter and Facebook, in blog posts, and the like. This is still a somewhat iffy proposition when it comes to “sentiment analysis”—determining what people think about the thing they’re commenting on, which is after all the crux of the issue. Algorithms are notoriously bad at identifying irony. Nonetheless, says Ghuneim, “Social is number one on every network executive’s desktop now. Three years ago I was getting, What are you talking about? Now it’s all incoming.”

To understand the idea’s appeal to advertisers, consider how Mediabrands, the IPG unit that runs the Media Lab, is using it. As the umbrella media-buying agency for the Interpublic Group, Mediabrands directs $34 billion in ad spending annually. “We want to buy low and get the most impressions,” says Stoller. So MagnaGlobal, Mediabrands’ intelligence arm, has started using engagement ratings to find undervalued television properties. “Nielsen ratings are apples,” Stoller continues. “What this brings into the conversation is oranges.”

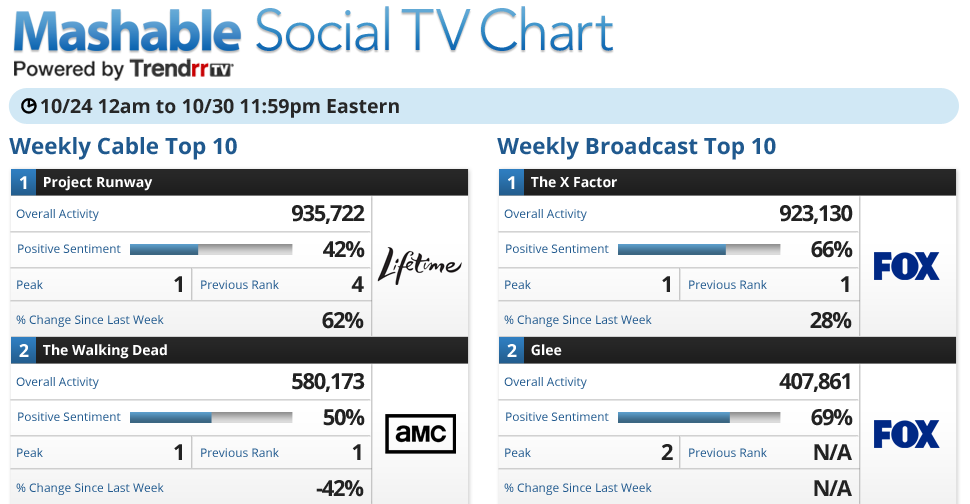

So what does engagement TV look like? There’s considerable overlap with ratings-driven TV, but there are also some marked differences. Cable wallops broadcast, as we can see from Trendrr’s most recent Social TV chart for Mashable (above): Except for The X Factor, people just don’t seem to care as much about the stuff they watch on the traditional networks. And yet, on a CPM basis, it costs at least three times more to buy air time on a popular broadcast show than it does on cable. So you can see how Magna might spot some bargains.

The networks view social engagement from an entirely different perspective—as a way to identify shows that ought to be worth a premium. “Icing on the cake of solid ratings,” as Simon Dumenco recently put it in Ad Age. But it’s the audience that really stands to benefit.

The hope is that engagement can keep good shows on the air—that it can prevent another debacle on the order of Star Trek. Conversely, it would also be nice if falling engagement levels prompted producers to rethink a faltering series, or encouraged network programmers to kill off a show that was living past its prime. But I suspect that as more and more viewers engage with shows through social media, what we’ll see is a gradual convergence of ratings and engagement—that the most popular shows will also be the most talked-about, and that as shows lose popularity they’ll also generate less chatter. That’s certainly what’s suggested by Glee, which has one of the most engaged audiences on TV—and whose ratings have dropped this season in tandem with the amount of online chatter it has generated. The truly interesting programs, whether you’re an ad buyer or a television viewer, will be the ones that buck this trend.

Comments

Michael Girard

- December 6, 2011

Just a great article. Very insightful and should help steer thinking about social tv away from being seen as a second screen app development process but into an actual metric that encompasses a number of social media industry insights, such as engagement, community advocacy, AND second screen usage etc.

Michael Girard

Community Engagement, Radian6