November 3, 2009

Guest post by PETER SACZKOWSKI

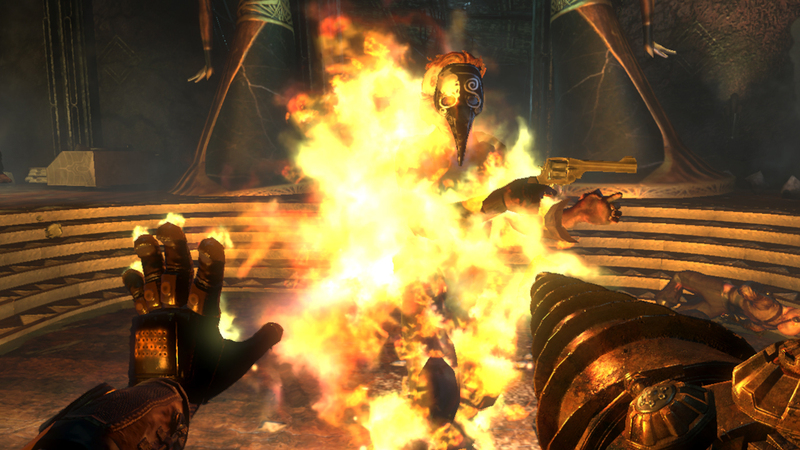

When Take Two Interactive lifted the embargo on previews of BioShock 2 last week, gamers discovered a major twist to the storyline. The teaser trailer and ad campaign for the sequel had focused heavily on an invincible cyborg known as the Big Sister as your new nemesis, stalking you as you traverse the underwater city of Rapture ten years after the demise of of its founder, Andrew Ryan. Now we learn that this idea has been scrapped because, as senior producer Melissa Miller explained, the development team at 2K Marin felt that fighting and never defeating the Big Sister time and time again would not provide the satisfaction gamers got from their encounters with the Big Daddies in BioShock.

Instead, players will find multiple Big Sisters to fight and defeat throughout the game. Replacing the Big Sister as Rapture’s new mastermind is Dr. Sophia Lamb, a clinical psychiatrist turned altruistic despot who believes that every one of our actions should contribute to the greater good. The change offers a good example of how storyline has to be subservient to gameplay. This has big implications, not just for the followup to the best-selling game but for the movie that’s in the works as well.

Unfortunately for BioShock fans, they will be waiting until 2010 for their next Rapture fix: the game sequel has been pushed back to February 9, and the BioShock movie is only now getting back on track after Universal put it on hold in a budget panic last spring. Now the picture is to be directed not by Gore Verbinski, who had developed the property, but by a little-known Spanish director, Juan Carlos Fresnadillo, with Verbinski producing.

More unsettling still, Ken Levine, the game’s originator, is playing only a small part in either project. 2K Marin promises an engrossing storyline and single-player experience, inspired by the original but expanding on almost every aspect. But with Levine working on his own project and many of BioShock 2’s resources focused on a multiplayer experience that is completely foreign to the first title, the team at 2K Marin has a lot to prove.

Translating an interactive game to the passive cinema has its own challenges, as demonstrated by Uwe Boll’s numerous failures. Gamers can take their stories very seriously—witness the innumerable forums on whether story matters in games and the “dev diaries,” like those for the upcoming Avatar game adaptation, that are devoid of any discussion of gameplay. Like fans of a best-selling novel, gamers can be upset if not outraged by a storyline that doesn’t live up to expectations. Yet writers and directors have to be sensitive not only to the storyline but also to the gameplay elements and how they make players feel.

None of this has kept film studios from taking video games seriously. Even games with no discernible storyline are being snapped up: Universal recently bought Asteroids, the classic ’80s arcade shooter, after a fight with three other studios. But even in games like BioShock, which won widespread praise for its narrative sophistication, the storyline suffers from some inherent limitations.

In a February 2008 appearance at the Game Developers Conference, Levine declared that there are three different demographics that any video game developer must consider to be successful. Most players fall into the category Levine calls level 1. They care little about the story; mainly their focus is on where they have to go and who they have to kill. The somewhat more involved gamer enjoys the story arc but has little real interest in the characters or in the larger narrative. These people don’t just want to know where to go and who to kill; they’d also like to know why. The level 3 gamer, Levine said, is “like the weird kid in the back of the classroom who’s writing all the Nirvana lyrics on his notebook.” These people will take the characters and story very seriously.

The preponderance of level 1 gamers means the game has to be directed toward them—which suggests that most games, to be successful, must appeal to the lowest common denominator. “If you want people to follow your plot,” Levine declared at GDC, “it has to be really fucking stupid.” He offered BioShock as an example: the plot basically consists of getting a submarine and then, after the sub is destroyed, trying to kill Andrew Ryan. Without this simplicity, says Levine, most gamers would be lost early on.

But of course, the game also needs to appeal to the geeky kid at the back of the class. To do that, Levine used what he sees as gaming’s narrative strength: the ability to enable players to “pull” narrative elements to themselves. This “pulling” ability is really a function of players’ freedom to explore and experience as much or as little of the game world as they’d like. Players who follow the game’s linear path will learn very little about the story and the universe it plays out in. But geek fans can explore all they want. In BioShock they’ll find audiologs documenting Rapture’s past, graffiti bearing clues about what happened to Rapture before their arrival, and the bodies of those murdered by the lunatics who populate Rapture now. In this way the geek fans “pull” the story of Rapture to themselves, even while the main storyline remains skeletal.

Levine contrasted this with the “pushing” structure of films: In movies, the director chooses what the audience sees and hears; the audience gets no choice about how much to experience. This could be a problem for anyone trying to turn BioShock—or any other game—into a movie. Since the story is secondary in most games and making it optional is a possibility, it makes sense to keep the narrative simple to avoid detracting from the gameplay and confusing the uncommitted. But any movie that relies on such a skeletal storyline is not likely to be too satisfying. And since all the information that geek fans get from exploring the world of BioShock pertains to Rapture’s past, the filmmakers will have a hard time appealing to them without spending most of the movie on the failed Utopia’s backstory.

Of course, narrative is less important if filmgoers aren’t looking for a smart movie. It wouldn’t be a huge surprise if Hollywood saw video games as nothing more than a source of empty popcorn flicks—in which case, you might conclude that video games appeal to studio execs not in spite of their narrative shortcomings but because of them. Yet the recent failure of such intellectually stunted movies as Land of the Lost, Will Ferrell’s $100 million bomb for Universal, and the Bruce Willis sci-fi flick Surrogates suggests that audiences might not be as dumb as studios think.

So Fresnadillo and Universal are left with a conundrum: They can either push as much BioShock lore into the movie as possible to appeal to ardent fans and risk alienating everybody else; or they can heed Levine’s advice to game developers and take their chances with something mindless. If they choose that route, they’ll leave the game’s real fans with little to pull from a dumbed-down experience.

Comments

Comments are closed here.