Trent Reznor. Photographs by Robert Maxwell

THE INITIAL CLUE was so subtle that for nearly two days, nobody noticed it. On February 10, 2007, the first night of Nine Inch Nails’ European tour, T-shirts went on sale at a 19th-century Lisbon concert hall with what looked to be a printing error: Random letters in the tour schedule on the back seemed slightly boldfaced. Then a 27-year-old Lisbon photographer named Nuno Foros realized that strung together, the boldface letters spelled “i am trying to believe.”

Foros posted a photo of his T-shirt on the Spiral, the Nine Inch Nails fan forum. People started typing “iamtryingtobelieve.com” into their Web browsers. That led them to a site denouncing something called Parepin, a drug apparently introduced into the US water supply. Ostensibly, Parepin was an antidote to bioterror agents, but in reality, the page declared, it was part of a government plot to confuse and sedate citizens. Email sent to the site’s contact link generated a cryptic auto-response: “I‘m drinking the water. So should you.” Online, fans worldwide debated what this had to do with Nine Inch Nails. A setup for the next album? Some kind of interactive game? Or what?

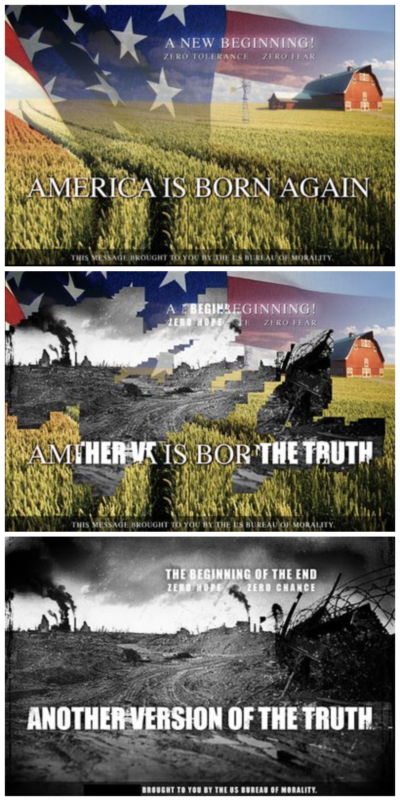

A few days later, on February 14, a woman named Sue was about to wash a different T-shirt, which she had bought at one of the Lisbon shows, when she noticed that the tour dates included several boldface digits. Fans quickly interpreted this as a Los Angeles telephone number. People who called it heard a recording of a newscaster announcing, “Presidential address: America is born again,” followed by a distorted snippet of what could only be a new Nine Inch Nails song. Then, a woman named Ana reported finding a USB flash drive in a bathroom stall at the hall where the band had been playing. On the drive was a previously unreleased song, which she promptly uploaded. The metadata tag on the song contained a clue that led to a site displaying a glowing wheat field, with the legend “America Is Born Again.” Clicking and dragging the mouse across the screen, however, revealed a much grimmer-looking site labeled “Another Version of the Truth.” Clicking on that led to a forum about acts of underground resistance.

All this activity had been set in motion months before. Trent Reznor, the singer-songwriter behind Nine Inch Nails, had been recording Year Zero, a grimly futuristic suite evoking an America beset by terrorism, ravaged by climate change, and ruled by a Christian military dictatorship. “But I had a problem,” he recalls, lounging on a second-floor deck of the house he’s remodeling in Beverly Hills: how to provide context for the songs. In the ’60s, concept albums came with extensive liner notes and lots of artwork. MP3s don’t have that. “So I started thinking about how to make the world’s most elaborate album cover,” he says, “using the media of today.”

Years earlier, Reznor had heard about a complex game played out over many months, both online and in the real world, in which millions of people across the planet had collectively solved a cascading series of puzzles, riddles, and treasure hunts that ultimately tied into the Steven Spielberg movie A.I.: Artificial Intelligence. Developed by Jordan Weisman, then a Microsoft exec, it was the first of what came to be called alternate reality games — ARGs for short. After leaving Redmond, Weisman founded a company called 42 Entertainment, which made ARGs for products ranging from Windows Vista to Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest. Reznor wanted to give his fans a taste of life in a massively dysfunctional theocratic police state, and he decided that a game involving millions of players worldwide would help him do that in a big way.

Reznor was stepping into a new kind of interactive fiction. These narratives unfold in fragments, in all sorts of media, from Web sites to phone calls to live events, and the audience pieces together the story from shards of information. The task is too complicated for any one person, but the Web enables a collective intelligence to emerge to assemble the pieces, solve the mysteries, and in the process, tell and retell the story online. The narrative is shaped — and ultimately owned — by the audience in ways that other forms of storytelling cannot match. No longer passive consumers, the players live out the story. Eight years ago, this kind of entertainment didn’t exist; now dozens of such games are launched every year, many of them attracting millions of followers on every continent.

How could this work for Year Zero? Reznor had spent a long time thinking and writing about the future dystopia he imagined. Now he wanted to share this story with his fans. He filled in the contact form on 42 Entertainment’s Web site and clicked Send.

How could this work for Year Zero? Reznor had spent a long time thinking and writing about the future dystopia he imagined. Now he wanted to share this story with his fans. He filled in the contact form on 42 Entertainment’s Web site and clicked Send.

WHEN WEISMAN OPENED Reznor’s email at his lakefront house near Seattle, he had barely heard of Nine Inch Nails. Slender and soft-spoken, with curly dark hair and a salt-and-pepper beard that gives him a vaguely Talmudic appearance, he’s not big on hardcore industrial rock. His experience is more in game design and social interaction, two fields he views as intimately conjoined. “Games are about engaging with the most entertaining thing on the planet,” he says, sipping coffee in his guesthouse, “which is other people.”

In 2001, Weisman was creative director of Microsoft’s entertainment division, which was developing the Xbox and a number of videogames—including one based on A.I.—to support its launch. The A.I. game never materialized, but the ARG Weisman created was phenomenally successful. He left Microsoft and in 2003 decided to do ARGs full-time, launching 42 Entertainment as a boutique marketing firm. He took the name from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, which maintains that “the Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything” is in fact 42. The company’s first game, ilovebees, had people answering pay phones around the world in the weeks leading up to the release of Halo 2. One player even braved a Florida hurricane to take a call in a Burger King parking lot.

Similar games have been used to launch scores of products in the years since. GMD Studios, a Florida outfit, staged a fake auto theft to begin a game for Audi that drew more than 500,000 players. A London studio called Hi-Res used television ads and specially made chocolate bars, among other things, in a still-talked-about game touting J.J. Abrams’s Lost. More recently, someone — not 42 — has been planting enigmatic clues on Web sites and fake MySpace profiles to promote a film Abrams is producing that so far is best known by the codename Cloverfield. What’s all this about a Japanese drink called Slusho? And what does it have to do with the sudden appearance of a Godzilla-like monster in New York Harbor? Abrams fans have been falling all over themselves to figure it out.

“When done well, ARGs can be extraordinarily effective,” says Ty Montague, creative director of the J. Walter Thompson ad agency. That’s because the games offer marketers a solution to a growing problem: how to reach people who are so media-saturated they block all attempts to get through. “Your brain filters it out, because otherwise you’d go crazy,” Weisman says. That’s why he opted for a “subdural” approach: Instead of shouting the message, hide it. “I figured that if the audience discovered something, they would share it,” he explains, “because we all need something to talk about.”

The ARG for A.I. began with an obscure credit for a “sentient machine therapist” in both the trailer and a prerelease promotional poster. Soon someone — all signs point to a member of Weisman’s group — wrote Harry Knowles at Ain’t It Cool News, suggesting he Google the therapist’s name. That led to a maze of bizarre Web sites about robot rights and a phone number that, when called, played a message from a woman whose husband had just died in a suspicious boating accident. Within 24 hours, thousands of people were trying to figure out what had happened.

Weisman had long been working toward that moment. Severely dyslexic as a kid, his world changed when he was introduced to Dungeons & Dragons. “Here was entertainment that involved problem solving and was story-based and social,” he says. “It totally put my brain on fire. What we’re doing now is a giant extrapolation of sitting in the kitchen playing D&D with friends. It’s just that now our kitchen table holds 3 million people” — the number that ultimately engaged with the A.I. game.

During the development of that first ARG, Weisman argued that no puzzle would be too hard, no clue too obscure, because with so many people collaborating online, the players would have access to every conceivable skill set. Where he erred was in not following that idea to its logical conclusion. “Not only do they have every skill on the planet,” he says, “they have unlimited resources, unlimited time, and unlimited money. Not only can they solve anything, they can solve anything instantly.” Weisman dubbed his game the Beast, because originally it had 666 pieces of content. But as the players burned through those and clamored for more, the name took on a different meaning. He had created a monster.

Weisman and Spielberg viewed the Beast as an extension of A.I. But the bill to fund it came out of the film’s marketing budget, and the ARG certainly created buzz for the movie. Meanwhile, the Internet was transforming marketing. Western commerce had been built on a clear proposition: I give you money, you give me something else of value. But like a rug merchant who offers prospective buyers tea before discussing his wares, the Internet was beginning to engage and entertain customers — whether with free singles on iTunes or an ARG that could run for months — before asking them to part with their money. “All marketing,” Weisman says, “is headed in that direction.”

Alex Lieu, Susan Bonds, and Jordan Weisman of 42 Entertainment, which pioneered alternate reality games.

FOR NINE INCH NAILS fans, the unfolding of the Year Zero game was as puzzling as it was exciting. “We didn’t know where it would go,” says Cameron Ladd, a 19-year-old community college student in rural Ohio who helps moderate the Nine Inch Nails fan forum Echoing the Sound. “We had no idea of the scope. That was the most fun — not knowing what would come next.” Debates raged as to whether it had anything to do with Philip K. Dick or the Bible, how it compared with Children of Men or V for Vendetta, and why the Year Zero Web sites kept referring to something called the Presence, which appeared to be a giant hand reaching down from the sky. The band’s European tour dates became the object of obsessive attention. “It was like, bang-bang-bang — there were so many things happening at once,” Ladd says. “It was one gigantic burst of excitement.”

Fans in Europe were so eager to find new flash drives that they ran for the toilets the moment the concert venue doors opened. On February 18, at the Sala Razzmatazz in Barcelona, someone scored. The drive contained an MP3 file of a new Nine Inch Nails song that trailed off into the sound of crickets.

But when the cricket sounds were run through a spectrograph, they yielded a series of blips that gradually resolved into a phone number in Cleveland, Ohio. People who dialed this number (and some 1.7 million did) heard a horrific recording from a mysterious organization called US Wiretap: a young woman on her cell phone at an underground nightclub, with shrieking and gunshots in the background, screaming hysterically that someone had come into the club and killed her friend and that the cops had locked everybody inside and she was going to die.

A visit to uswiretap.com (“A Partnership Corporation of the Bureau of Morality”) revealed that federal agents had bolted the doors to the club, a known “resistance” hangout, while the 112 people inside spent two days tearing one another to shreds in a mad frenzy.

Audio PlayerThe clues on the flash drives were typical of what makes a good ARG work. They were hard to spot and even harder to decipher, but because the narrative was being pieced together online, you didn’t have to be a propellerhead to follow it. “Our assumption,” says Sean Stewart, the game’s head writer, “was never that there’s a continent of people who love nothing better than to do spectrogram analysis. But there are always a few, and if you make a world that’s compelling enough, there’ll be a lot to do even if you’re not interested in the really arcane stuff.”

Most fans didn’t realize their progress was being monitored nonstop. Unlike less interactive forms of entertainment, ARGs require a close collaboration between the puppet masters — the unseen figures who create the story — and the audience. “The makers and the consumers are in a tango,” Stewart says. “It’s a dance, it’s passionate, and sometimes there are sinister overtones. It creates a unique dynamic.”

After every gig, Reznor rushed back to his hotel so he could watch the action on fan forums and in chat rooms unfold on his laptop. “I couldn’t wait,” Reznor says. “‘Did they find it? Did they find it?’ I know it sounds nerdy, but it was exciting.” The 42 Entertainment team, working out of a cramped loft in downtown Pasadena, California, kept an even closer watch. They had to make sure the players didn’t get frustrated or go too far down a wrong path.

It didn’t take long to spot the first problem. On several sites, brief snippets of text from mildly subversive books — One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Slaughterhouse-Five, Heather Has Two Mommies — had been scanned into the background to provide visual interest. Players, however, were interpreting them as clues and trying to figure out what they meant.

At 42 Entertainment, panic set in. “It’s a silent contract,” explains Steve Peters, the game designer charged with tracking player progress. “We respect you — which means we’re not going to lead you along by the nose and then not give you anything.” They decided to add a clue suggesting that the texts were from banned books.

There were more complications to come. Reznor presumed that weeks before the CD reached Wal-Mart and Best Buy, someone would upload it to the BitTorrent sites, which his most avid fans would be carefully monitoring. So he planted hints in the music — a few seconds recorded out of phase on “The Great Destroyer,” for instance. Played on a monaural device, the music briefly canceled itself out, leaving nothing except a barely audible voice saying something like “red horse vector.” At redhorsevector.net, players would find a top-secret report suggesting the source of the nightclub massacre — a weaponized virus called Red Horse that caused acute homicidal psychosis.

Surprisingly, though, no one was uploading the album. Reznor had assumed it would hit the peer-to-peer sites by mid-March, but at the end of that month there was still no sign of it. Without the music, only a handful of new clues were coming out. “The fans were getting antsy,” says Alex Lieu, 42 Entertainment’s creative director. “So were we. Trent was stunned. And the whole time we were thinking, ‘When is someone going to steal this album?’”

REZNOR WOULD LIKE TO MAKE ONE THING about the Year Zero game perfectly clear: “It’s not fucking marketing. I’m not trying to sell anything.” That’s why he paid for the game himself, out of his recording budget. For a while, he didn’t even tell his label what he was doing. But the game was extremely effective at generating excitement. Every time a song was leaked, the message boards were swamped. By the time the album hit store shelves in April, 2.5 million people had visited at least one of the game’s 30 Web sites. The buzz was so great that Interscope chair Jimmy Iovine — Reznor’s label boss at Universal Music at the time — called Weisman to talk about buying 42 Entertainment.

From 42’s perspective, it hardly matters whether you call the game “marketing” or not. What matters is that someone — Reznor, Microsoft, Disney — writes a check. And, for now, the checks generally come from companies trying to sell something. As a result, many ARG developers want to break out of marketing entirely and find another way to make money. Novelists, film directors, and television producers get to tell their own stories; why not ARG-makers? GMD Studios, the company behind the ARG for Audi, has been running a game that it hopes will spawn graphic novels and maybe a TV show. In September, Stewart and two other longtime associates of Weisman’s left 42 Entertainment to start a new company, Fourth Wall Studios, with similar ambitions.

So far, however, no one has managed to create an ARG that can sustain itself through advertising, subscription fees, or any other model. The most ambitious attempt was Perplex City, a vast treasure hunt staged by a London company called Mind Candy, which has received $10 million in venture capital — a first in ARG-land. Perplex City was said to be a locale in an alternate universe whose most powerful artifact, a polished metal cube, had been stolen and buried somewhere on Earth; whoever found it stood to receive a $200,000 reward. Clues were hidden on a series of cards sold in toy shops, bookstores, and online for about $1 apiece.

VCs had visions of Pokémon dancing in their heads. But though 50,000 people in 92 countries registered for the game, the cards turned out to be difficult and expensive to produce. Last June, not long after the cube was unearthed in a forest in England, a planned second season was abruptly canceled. “I’m still convinced there are exciting commercial models that no one has found just yet,” says Michael Smith, Mind Candy’s CEO. “It’s a wonderful world we created, and I very, very much want to relaunch it.” Unfortunately, he doesn’t know when that will happen.

January 1, 2008

January 1, 2008