“Lonely Planet” and its companion piece, “Blind Spots” (see below), were written in response to two online advertising fads that were demonstrably unproductive: Second Life and video games. No, Second life was not the metaverse, and no, gamers don’t pay attention to ads in games, because they’re too busy playing.

FOR MONTHS, Michael Donnelly had been hearing all about the fantastic opportunities in Second Life.

As worldwide head of interactive marketing at Coca-Cola, Donnelly was fascinated by its commercial potential, the way its users could wander through a computer-generated 3-D environment that mimics the mundane world of the flesh. So one day last fall, he downloaded the Second Life software, created an avatar, and set off in search of other brands like his own. American Apparel, Reebok, Scion — the big ones were easy to find, yet something felt wrong: “There was nobody else around.” He teleported over to the Aloft Hotel, a virtual prototype for a real-world chain being developed by the owners of the W. It was deserted, almost creepy. “I felt like I was in The Shining.”

Yet Donnelly decided to put money into Second Life anyway. He’s no digital naïf: When he joined Coke last summer, the company was being ridiculed for its huffy response to a spate of Web videos showing the soda geysers that erupt when you drop Mentos into Diet Coke. Within weeks, Donnelly had Coke and Mentos sponsoring a contest on Google Video that’s gotten more than 5.6 million views. But Second Life was different. “Many places you go, there’s still nobody there,” he concedes. That’s certainly the case with Coke’s Virtual Thirst pavilion, where you can long linger without encountering another avatar. “But my job is to invest in things that have never been done before. So Second Life was an obvious decision.”

As with Donnelly and Coca-Cola, so with David Stern and the National Basketball Association. Stern, who’s been NBA commissioner since 1984, was introduced to Second Life in July 2006, at the annual media and technology retreat hosted by New York investment banker Herbert Allen in Sun Valley, Idaho. Second Life’s creator, Philip Rosedale, was one of the presenters, as was Chad Hurley, cofounder of YouTube, another company Stern had never heard of. “My initial impression was, ‘Don’t people have better things to do with their lives?’ Then I said, ‘Stupid! You’re not the audience.’ ”

As with Donnelly and Coca-Cola, so with David Stern and the National Basketball Association. Stern, who’s been NBA commissioner since 1984, was introduced to Second Life in July 2006, at the annual media and technology retreat hosted by New York investment banker Herbert Allen in Sun Valley, Idaho. Second Life’s creator, Philip Rosedale, was one of the presenters, as was Chad Hurley, cofounder of YouTube, another company Stern had never heard of. “My initial impression was, ‘Don’t people have better things to do with their lives?’ Then I said, ‘Stupid! You’re not the audience.’ ”

Stern left Sun Valley convinced he’d seen the future, and he was about half right. YouTube has become a powerful tool for pro basketball. The site’s NBA channel, launched in February, has already garnered some 14,000 subscribers; users have posted more than 60,000 NBA videos, which have been viewed 23 million times. But over at Second Life, where an elaborate NBA island went up in May, the action has been a bit slower. “I think we’ve had 1,200 visitors,” Stern reports. “People tell us that’s very, very good. But I can’t say we have very precise expectations. We just want to be there.”

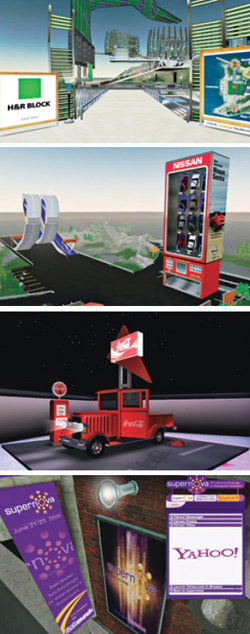

COKE AND THE NBA ARE hardly alone. Adrift in the uncharted sea that is Web 2.0 — YouTube, MySpace, social networking, user-generated content, virtual worlds — corporate marketers look at Second Life and see something to grab onto. At least 50 major companies have ventured into the virtual world to date, spending millions in the process. IBM has created a massive complex of adjoining islands dedicated to recruitment, employee training, and in-world business meetings. Coldwell Banker has opened a virtual real estate office. Brands like Adidas, H&R Block, and Sears have set up shop. CNET and Reuters have opened virtual bureaus there. It’s as if the moon suddenly had oxygen. Nobody wants to miss out.

Ever since BusinessWeek ran a breathless cover story titled “My Virtual Life” more than a year ago, reporters have been heralding Second Life as the here-and-now incarnation of the fictional Metaverse that Neal Stephenson conjured up 15 years ago in Snow Crash. (Wired created a 12-page “Travel Guide” last fall.) Unfortunately, the reality doesn’t justify the excitement.

He teleported to the Aloft Hotel. It was deserted, almost creepy. “I felt like I was in ‘The Shining.’ ”

Second Life partisans claim meteoric growth, with the number of “residents,” or avatars created, surpassing 7 million in June. There’s no question that more and more people are trying Second Life, but that figure turns out to be wildly misleading. For starters, many people make more than one avatar. According to Linden Lab, the company behind Second Life, the number of avatars created by distinct individuals was closer to 4 million. Of those, only about 1 million had logged on in the previous 30 days (the standard measure of Internet traffic), and barely a third of that total had bothered to drop by in the previous week. Most of those who did were from Europe or Asia, leaving a little more than 100,000 Americans per week to be targeted by US marketers.

Then there’s the question of what people do when they get there. Once you put in several hours flailing around learning how to function in Second Life, there isn’t much to do. That may explain why more than 85 percent of the avatars created have been abandoned. Linden’s in-world traffic tally, which factors in both the number of visitors and time spent, shows that the big draws for those who do return are free money and kinky sex. On a random day in June, the most popular location was Money Island (where Linden dollars, the official currency, are given away gratis), with a score of 136,000. Sexy Beach, one of several regions that offer virtual sex shops, dancing, and no-strings hookups, came in at 133,000. The Sears store on IBM’s Innovation Island had a traffic score of 281; Coke’s Virtual Thirst pavilion, a mere 27. And even when corporate destinations actually draw people, the PR can be less than ideal. Last winter, CNET’s in-world correspondent was conducting a live interview with Anshe Chung, an avatar said to have earned more than $1 million on virtual real estate deals, when Chung was assaulted by flying penises in a griefer attack.

One of the things you never see in Second Life is a genuine crowd — largely because the technology makes it impossible. In Stephenson’s Metaverse, corporations established their presence along a bustling, almost infinitely long street that residents could cruise at will. Second Life is different. Created by an underfunded startup using a physics engine that’s now years out of date, Second Life is made up of thousands of disconnected “regions” (read: processors), most of which remain invisible unless you explicitly search for them by name. Residents can reach these places only by teleporting into the void. And even the popular islands are never crowded, because each processor on Linden Lab’s servers can handle a maximum of only 70 avatars at a time; more than that and the service slows to a crawl, some avatars disappear, or the island simply vanishes. “It’s really the software’s fault,” says Andrew Meadows, Linden Lab’s senior developer. “Way back when, we used to say, ‘This is not going to scale.’ ”

AND YET, SO EAGER are corporate marketers to get in that a small industry has sprung up to help. Business appears to be good — very good. “We have basically not made any sales calls,” says Sibley Verbeck, founder and CEO of the Electric Sheep Company, which has built in-world presences for such clients as AOL, Major League Baseball, the NBA, Nissan, Pontiac, and Sony BMG Music. “We would like to. But we can hardly keep up with the Fortune 500 companies that are contacting us.”

AND YET, SO EAGER are corporate marketers to get in that a small industry has sprung up to help. Business appears to be good — very good. “We have basically not made any sales calls,” says Sibley Verbeck, founder and CEO of the Electric Sheep Company, which has built in-world presences for such clients as AOL, Major League Baseball, the NBA, Nissan, Pontiac, and Sony BMG Music. “We would like to. But we can hardly keep up with the Fortune 500 companies that are contacting us.”

From an obscure background in computational linguistics, Verbeck has emerged as perhaps the world’s leading evangelist for Second Life business opportunities. Dressed in blue jeans and a flannel shirt, his long, dark hair flowing from beneath a wide-brimmed black hat, he looks like a diminutive New Age lumberjack. But Verbeck is also oddly charismatic, with an almost messianic belief in the potential of virtual worlds.

Electric Sheep launched with the mission of promoting Second Life by developing software to make the experience less clunky and off-putting. Bringing in big corporations was a way of generating money and adding new in-world attractions. Marketers weren’t interested at first, but that changed after the May 2006 BusinessWeek story and Rosedale’s appearance at Sun Valley a couple of months later. “By September, it was crazy,” says Giff Constable, an investment banker who joined Electric Sheep after falling in love with Second Life. “A lot of people who missed MySpace said, ‘You know what? We shouldn’t let that happen again.’ ”

What do marketers want when they call Electric Sheep? “They don’t know,” Verbeck says. “Mostly it’s ‘We’ve been reading about virtual worlds — is there anything there for us?’ ” Almost inevitably, the answer is yes. The cost varies greatly: A company can stage an in-world speaking event for as little as $10,000, but hiring Electric Sheep or one of its competitors to create a full-time presence, with a private island and a lot of virtual construction, could run several hundred thousand dollars a year. (Linden Lab leases virtual land to cover its server costs but doesn’t take a cut of what companies spend establishing their presence there.) Opt for a really elaborate build, hold frequent events to keep people coming back, and hire an employee or two to keep things running, and the budget could easily hit $500,000 a year.

Joseph Jaffe, the marketing consultant who advised Coke on its in-world presence, dismisses the notion that such efforts might not be worthwhile. “The learning is now,” Jaffe says. “You are a pioneer, and with that comes first-mover advantage” — that chestnut from the Web 1.0 boom. And the paltry numbers? “This is not about reach anymore. This is about connecting. It’s about establishing meaningful, impactful conversations. So when people ask, ‘Why Second Life?’ I ask, ‘Why not?’ ”

Jaffe logs on to show off Coke’s Virtual Thirst pavilion, which was created by Millions of Us, a Bay Area company that does in-world builds. He’s a close match for his avatar, Divo Dapto, a trim little figure clad in roll-up jeans and a red-on-white Virtual Thirst T-shirt. “You never know who you’re going to meet,” Jaffe says as Dapto soars toward the Virtual Thirst pavilion.

The Coke build is expansive, elaborate, and of course empty. But Coca-Cola has a plan. It’s sponsoring a contest to create a Virtual Thirst vending machine that it hopes will become ubiquitous in Second Life, just as Coke machines are everywhere in real life. Jaffe professes to be overwhelmed by the number of entries, which he characterizes as “well north of 100.”

Suddenly, another avatar materializes. “Ah, there you go,” Jaffe exclaims. “Someone’s just arrived! I think she’s from Japan.” As he speaks, Dapto starts air-typing in the weird way that Second Life avatars do, trying to chat up the new Japanese girl. She looks around, then teleports someplace else.

YOU MIGHT WONDER what Coke is doing in such a place. “It had a lot to do with hype,” admits Michael Donnelly.

Still, despite isolated reports of corporate dissatisfaction with Second Life, the influx continues. Electric Sheep claims to be turning away business. IBM has set up a virtual worlds business unit. Millions of Us, which has also built corporate presences for Intel, Microsoft, Sun, and — full disclosure — Wired, is constructing a virtual Hollywood Hills for show business companies.

What’s behind this stampede is not that hard to divine. “A terror has gripped corporate America,” says Joseph Plummer, chief research officer at the Advertising Research Foundation, an industry think tank. Plummer has been around Madison Avenue since the early ’60s, when modern advertising techniques materialized. “The simple model they all grew up with” — the 30-second spot, delivered through the mass reach of television — “is no longer working. And there are two types of people out there: a small group that’s experimenting thoughtfully, and a large group that’s trying the next thing to come through the door.” Second Life appeals to the latter — the ones who are afraid of missing out, who don’t consider half a million dollars to be a lot of money, and who haven’t figured out (or don’t want to admit) that Second Life is less than the bold new frontier it appears to be.

“For people who’ve grown up in analog, Second Life is not that hard to understand,” says Rishad Tobaccowala, CEO of Denuo, a consulting arm of the global ad giant Publicis Groupe. “I have a store in the real world; I have a store in the virtual world.” In contrast, the kind of digital marketing that actually works requires a conceptual leap. Successful online marketing is targeted and specific, like direct mail — but it’s direct mail in a fun house, where the recipients can easily seize control of what the mail says, where it goes next, and how it gets there. You need to know how to buy up keywords to maximize search returns, how to make the most of recommendation engines, how to use the viral potential of Web video, how to monitor what’s being said in blogs and message boards, how not to blow it by trying to be deceptive. Building a corporate pavilion in Second Life doesn’t require any of these things. It’s simple and it’s obvious.

Virtual worlds will evolve, of course. It’s easy to imagine targeted in-world advertising, for example, or a 3-D version of MySpace. Although it won’t comment officially, IBM is understood to be working to create a “virtual universe” by building software that will allow avatars to leap from Second Life to World of Warcraft as easily as we now move from Google to Yahoo. The Internet will eventually be full of such 3-D environments; Second Life might even be one of them. But in the meantime, it’s just slurping up corporate dollars and delivering little in return.

“Companies say, ‘It’s an experiment’ — but what are they learning?” Tobaccowala asks. “Basically, they’re learning how to create an avatar and walk around in Second Life.” Which is fine if that’s what you want to do. Just don’t expect to sell a lot of Coke. ♦

Blind Spots

Embedding ads into videogames seemed like a good idea—too bad users didn’t notice them.

ON A RAINY DAY in February, a 25-year-old gamer named Adrian Sweeney arrives at an old World War II air base in the English countryside. He’s been promised £50 and the opportunity to spend an hour playing Need for Speed: Carbon, the hot new auto-racing game from Electronic Arts. In exchange, a behavioral research firm called Bunnyfoot will peek into his consciousness.

ON A RAINY DAY in February, a 25-year-old gamer named Adrian Sweeney arrives at an old World War II air base in the English countryside. He’s been promised £50 and the opportunity to spend an hour playing Need for Speed: Carbon, the hot new auto-racing game from Electronic Arts. In exchange, a behavioral research firm called Bunnyfoot will peek into his consciousness.

Sweeney sits patiently as a consultant, Alison Walton, straps a breathing monitor around his chest and attaches electrodes to his fingertips (to measure perspiration) and his face (to detect the muscle contractions that produce frowns and smiles). Then she sets up an infrared eye-tracking device that shows her a single blue dot wherever he looks on the video screen. The more focused his gaze, the bigger the dot.

Much depends on this dot. Need for Speed: Carbon is a money machine for EA — not just because it has sold more than 8.5 million copies at $30 a pop, but also because it’s full of ads. It’s one of more than 70 games that carry commercial messages, mostly on billboards and posters, that are sold and inserted by a Microsoft subsidiary called Massive. If Sweeney’s dot lands on anything advertisers have paid for, it suggests their money was well spent.

Moving to the next room, Walton watches representations of Sweeney on three screens — his face, rapt and impassive; his gaze, represented by the dot skittering across the gameplay; his vital signs, monitored in cool electronic blips. It’s obvious he’s not spending much time looking at ads; in fact, it’s all he can do not to run off the road. Among the few brands he remembers when the session is over are Chevrolet, Honda, Lamborghini, and Mazda — the car makes he had to choose from at the outset. Walton is not surprised. On action titles, every gamer she’s tested has been too engrossed in the game to pay attention to the ads.

“In-game advertising is a great idea — it’s just not being executed very well,” maintains Robert Stevens, Bunnyfoot’s cofounder. Good games, he continues, have a hypnotic effect. “Somebody who’s very engaged in a game is focusing on one thing to the exclusion of everything else. But while he’s in that trance state, he should also be reasonably suggestible. The question is, how do you put that suggestion in there?”

MADISON AVENUE IS ASKING the same thing. The ad market in games is tiny but growing fast: From just $56 million in 2005, the Yankee Group projects it will grow to $732 million by 2010. Advertisers are trying to reach the seemingly unreachable, the 18- to 34-year-old males who are spending more time with their consoles and less time watching TV. Game publishers want a way to offset ever-escalating development costs. Gamers themselves might find the experience more realistic — or they might just dismiss the whole thing as spam.

What if he could take that fake in-game ad for “The Goop” and replace it with a paid ad for real jeans?

None of this would have been possible as recently as seven or eight years ago. Graphics back then were so crude, and gamers considered so irredeemably geeky, that publishers usually had to pay brands for the right to use their names. PlayStation 2 and Xbox made the graphics acceptable, but brand logos still had to be burned into the disc, and few companies want to commit to an ad message a year in advance. Then a New York software exec named Mitch Davis noticed a billboard touting clothes from “the Goop” as he was playing Grand Theft Auto: Vice City. What if he could use the console’s Internet connection to replace the fake Goop ads with paying ads for real jeans? He could string together a “network” of game titles and enable advertisers to run campaigns, just as they do on TV. He could also target gamers as precisely as Web surfers — by demographic, location, even time of day.

Davis called his company Massive because the idea seemed, well, big. Technologically, ad-serving in 3-D isn’t that different from ad-serving on the Web: Create blank spots in the game — a billboard here, a drink machine there — and deliver the right images at the right time to fill them in. But since advertisers were willing to spend $20 to $30 per 1,000 gamers (well over the going rate for Web surfers), Davis was able to promise publishers $2 to $3 per Internet-connected game sold. By the end of 2005, Massive was delivering ads from brands like Honda and Nokia to games from Activision, Ubisoft, and others. A few months after that, he sold the company to Microsoft for a reported $200 million.

August 1, 2007

August 1, 2007